From the Left Bank with Love – Paris Iconic Hôtel Lutetia Joins the Mandarin Oriental Family

( words)

By Andreas Augustin

3 April 2025.

Spring has returned to Paris. Temperatures oscillate between 5 and 20°C. The city begins to blossom: chestnut trees lining the boulevards push forth their first buds, café terraces bustle with conversation, and the sidewalks once again welcome the unhurried pace of sun-chasers. On this day, amid the seasonal reawakening, the Hôtel Lutetia at the Rive Gauche – the only Palace-designated hotel on this side of the Seine in the heart of Saint-Germain-des-Prés — formally entered a new chapter in its already storied life—joining the Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group.

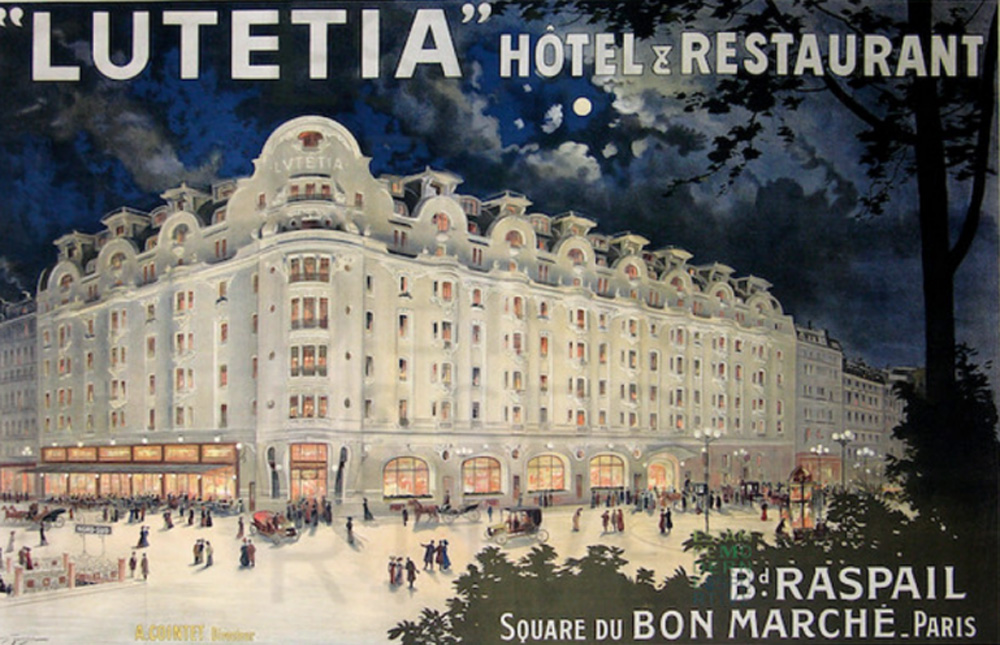

The Lutetia has long occupied a singular space in the Parisian hotel landscape—not merely as a luxury destination, but as a cultural institution. The Belle Époque hotel, completed in 1910 along Boulevard Raspail, owes its existence to the entrepreneur Aristide Boucicaut, owner of the elegant Le Bon Marché department store just across the street. Boucicaut envisioned a residence that would suit the lifestyle of his wealthy provincial clientele visiting Paris to shop. That luxurious life was short-lived: in 1914, the Lutetia was converted into a military hospital for wounded soldiers; during the Second World War, the hotel was requisitioned by the German occupying forces and used to house their military intelligence services. In 1945, it briefly became a sanctuary for Holocaust survivors—a plaque near the hotel entrance still commemorates this moment.

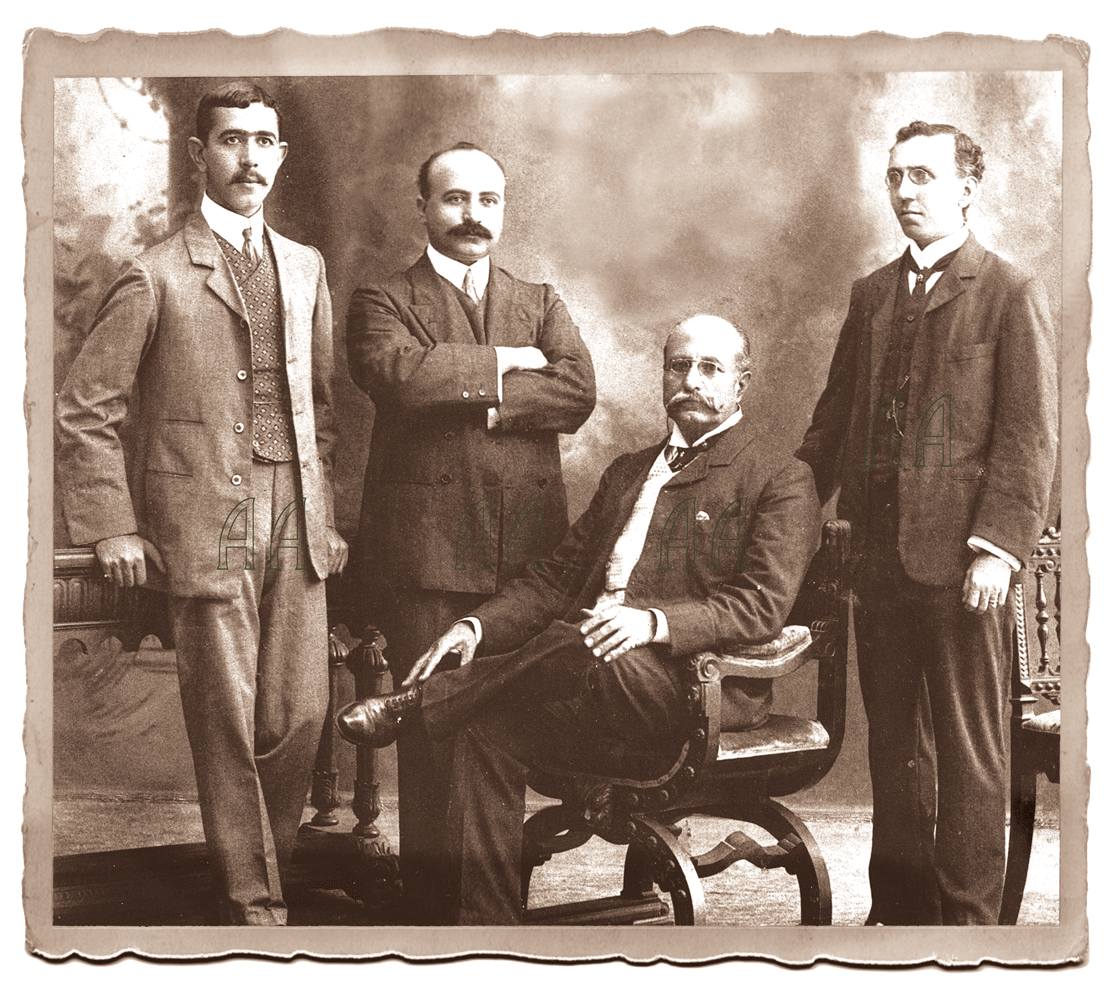

At the ribbon cutting: the Akirov family, Laurent Kleitman and Jean-Pierre Trévisan, General Manager of the Lutetia

At the ribbon cutting: the Akirov family, Laurent Kleitman and Jean-Pierre Trévisan, General Manager of the Lutetia

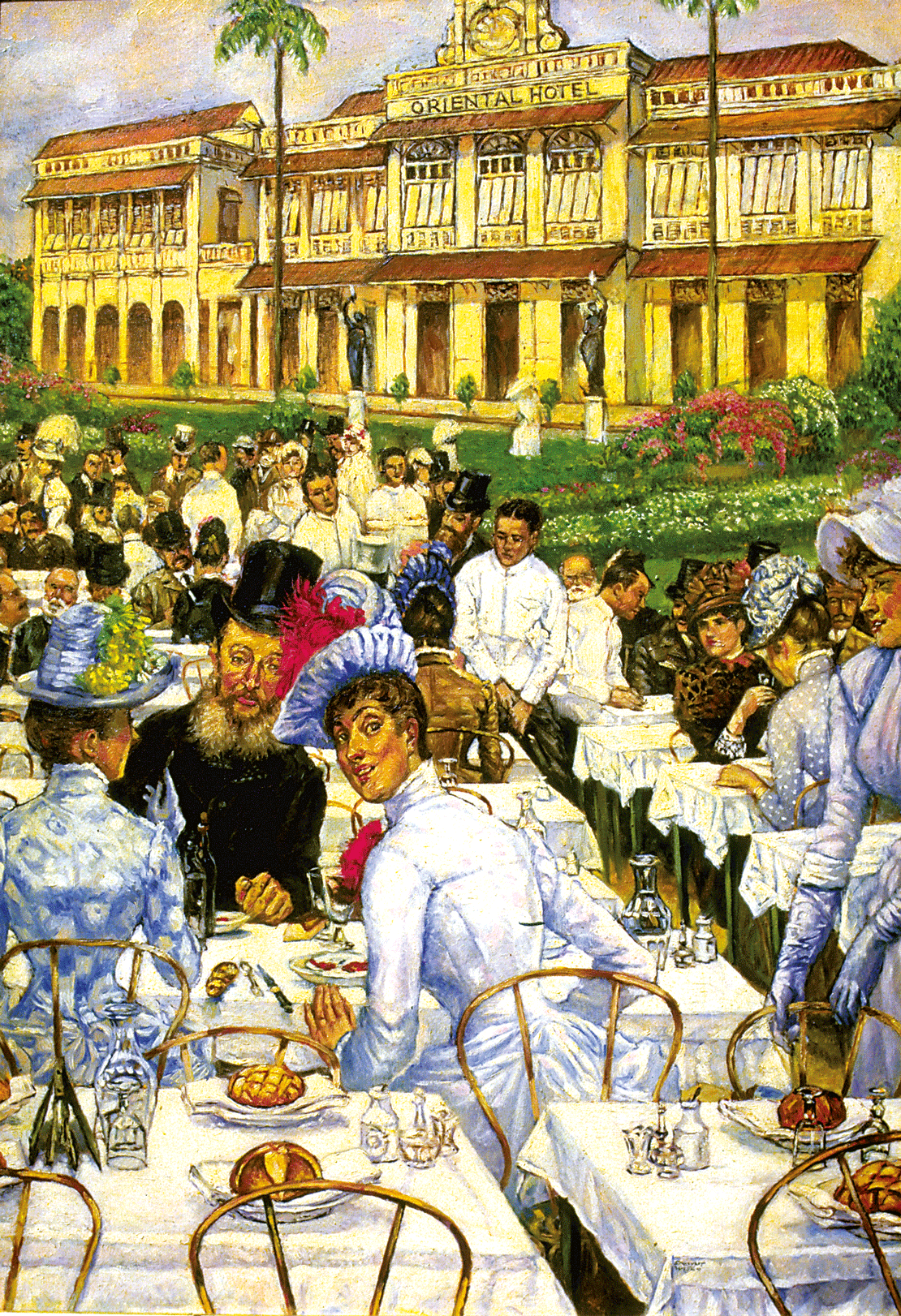

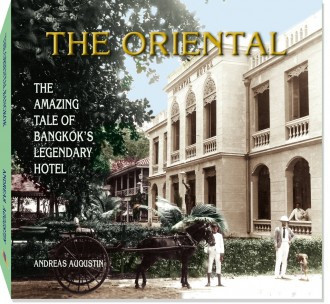

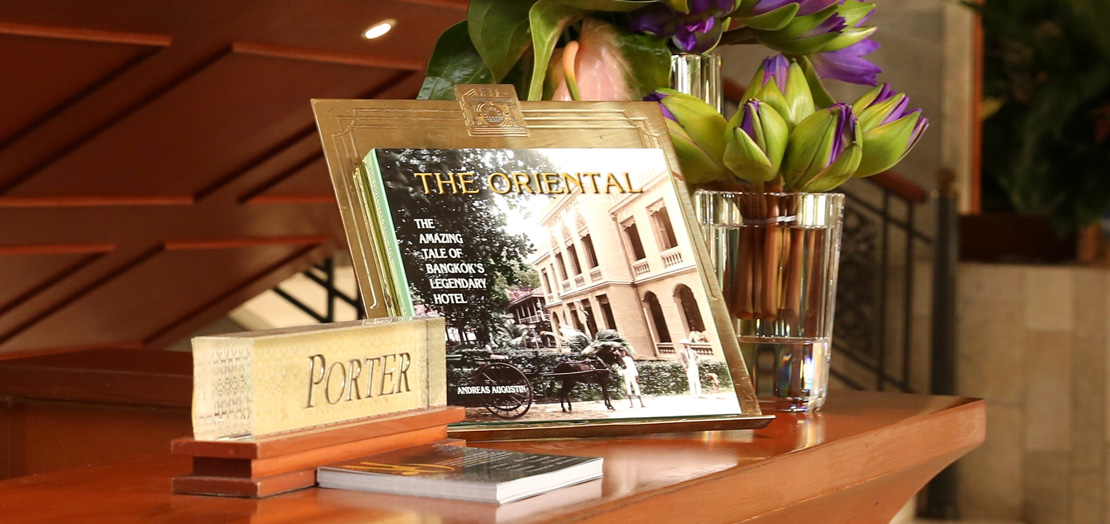

Back to the present. Present at the inauguration were the owning Akirov family, Laurent Kleitman, CEO of Mandarin Oriental, and COO Amanda Hyndman, who had just arrived from Hong Kong—an old friend from our collaboration at the Mandarin Oriental Bangkok, where we co-created the first coffee table book on the Oriental's history in our Edition Raconteur and established the permanent history exhibition The Oriental Journey together. Isn’t it remarkable how every historic hotel worth its name these days has carved out space for its own exhibition on hotel history—visible, professionally curated, and proudly in-house?

A site of intellectual gathering, political symbolism, and artistic resonance, the Lutetia now dons the livery of one of the most internationally revered hotel brands, and with that transformation comes a recalibration of identity. Jean-Pierre Trévisan, General Manager of the Lutetia, expressed candid optimism: the brand partnership, he noted, would offer visibility in markets previously unfamiliar to the hotel, particularly in Asia. Laurent Kleitman, a master of the well-turned speech, remarked in his stirring address that it is the human values which connect the Akirov family and the Mandarin Oriental Hotel Group.

To Mandarin Oriental’s credit, the hotel’s Parisian soul remains unbroken. The architectural and atmospheric language of the Left Bank persists: the jazz still flows in Bar Joséphine, the worn floorboards still whisper of literary ghosts. There is a deliberate preservation of place here. Slowly, the Asian signature that defines the Mandarin Oriental experience, will appear. In the scent of the hallways, in the gestures of hospitality, in the cadence of service. In its finest properties across Asia, the group delivers hospitality as ritual. In Paris, these signatures are less overt. Yet! Though subtle traces emerge: an exacting standard of attentiveness, a floral choreography of cherry blossoms, ranunculus, and flamingo lilies artfully arranged throughout the bar, and a remarkable culinary presence displayed in the precision of the hors d’oeuvres of the flying buffet. The potential for a deeper cultural layering remains tantalizingly just beneath the surface.

The coming months will slowly transform the Lutetia into a true Mandarin Oriental. A hint at the refined stand-up collar of an elegant Thai suit, the shimmering silk dresses of Siam. Maybe the gentle “Wai” of universal Thai greeting fame—now a global ambassador since the pandemic’s polite reshuffling of gestures. The air infused with the delicate scent of orchids, perhaps grown in the inner courtyard.

A whisper of the very enchantment that made the Mandarin Oriental in Bangkok the spiritual flagship of the entire group will change it all. Because here’s the thing: when someone walks into a Mandarin Oriental, they expect an Asian experience. Otherwise—why not just go to the Ritz?

Bar Joséphine — a floral choreography of cherry blossoms, ranunculus, and flamingo lilies artfully arranged for the ceremony.

The hotel's physical and symbolic transformation over the past decade has been significant. The Palace distinction, conferred in 2019, affirmed the Lutetia’s elevated status, distinguishing it as the only such designated property on the Left Bank. This accolade followed an ambitious four-year renovation (2014–2018), overseen by architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte and financed by the Alrov group, which acquired the hotel in 2010 for €145 million. The restoration, reportedly costing €200 million, revived original frescos and stucco, while reimagining 184 rooms and suites in an aesthetic of restrained elegance. A selection of these suites pays tribute to personalities such as Francis Ford Coppola and Isabelle Huppert, whose presence echoes the intellectual tone of the neighborhood.

The building rises majestically onto the boulevard. The corner tower, with its large rounded façade, gazes like the head of a cobra toward the Square du Bon Marché. Here stands a truly exceptional grand hotel — a magnificent edifice from the early 20th century. Opened in 1910, the Lutetia's founding connection to the oldest and most luxurious department store of the country – Le Bon Marché, established by the Boucicaut family in 1910, endures as both legacy and active collaboration.

The media continues to dwell—somewhat wearily—on the Lutetia’s complex wartime legacy, particularly its role during the German occupation. However, more compelling perhaps is its post-liberation moment: in 1944, General de Gaulle requisitioned the hotel to accommodate thousands of returning deportees. Archival images from Agence France-Presse document emaciated survivors dining in the hotel's restaurant in May 1945, and others consulting bulletin boards listing repatriated names. And by the way, isn’t it time we talk about this recurring theme? No grand Parisian hotel without its Wehrmacht chapter, no wine cellar that wasn’t allegedly walled up to protect vintage treasures from the Nazis. National pride, it seems, lies in denying the enemy access to the Bordeaux.

Jiasheng Wan, the hotel’s chef sommelier

Of the vintage bottles and the men who once knew them, none have survived the years. Today, the Lutetia’s ultra modern and elegant cellar holds some 20,000 bottles. The wine list spans 40 pages of selections. The original vaulted cellars from the early 20th century are under Jiasheng Wan, the hotel’s chef sommelier, who explains: „A 1997 Auxey-Duresses 1er Cru is our oldest wine.“ In-Cellar wine tastings are reserved for the in-residence clientele of the house. Wan: “Our most expensive wine is a Petrus 2014 at €7,800. I’m working on getting a Romanée-Conti.” The perennial bestseller, as expected, is the Chablis Village by the glass.

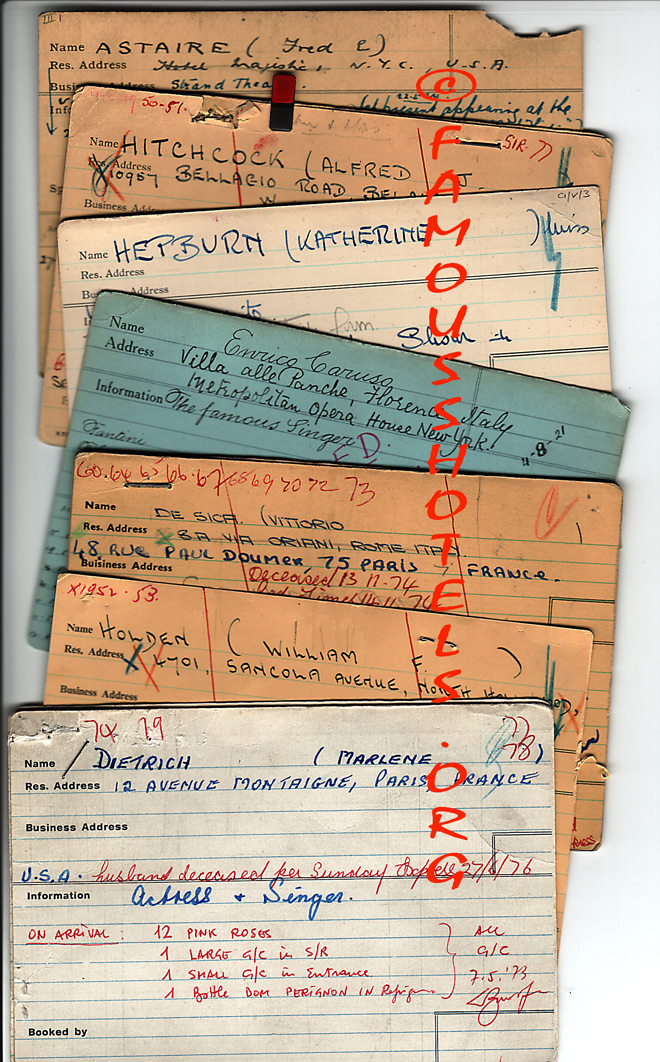

Famous Partons or: How Legends Are Constructed and How Songs Become Testimonies

There is a story that circulates, whispered with a certain Left Bank reverence: James Joyce wrote parts of Ulysses at the Hôtel Lutetia. It sounds beautiful. Almost believable. The address fits, the aura fits, the timeline—more or less—could be made to fit. And yet, it isn't true. Not quite. Joyce did complete Ulysses in Paris. He lived on the Rive Gauche, not far from the Lutetia. He passed its doors, perhaps even sat there briefly. But no credible record—no letter, no note, no eyewitness—places him writing at that hotel. Still, the idea persists. Because it is convenient. Because it flatters both hotel and guest. Because it gives us something to sip with our Bordeaux.

It is said that Serge Gainsbourg’s nocturnal wanderings were immortalized in Eddy Mitchell’s smoky ballad Au bar du Lutetia. It sounds perfectly plausible. The bar, the mood, the man. One imagines him slouched in a velvet banquette, murmuring something indecent over a Gauloise and a glass of bourbon. But the song never mentions him. Au bar du Lutetia conjures ghosts, yes—but none are named Serge. No factual record ties Gainsbourg to that bar in song. Still, the myth survives. Because it fits. Because Paris runs on the fumes of poetic association. Because sometimes, legend walks in after closing time, orders a drink, and never really leaves.

And so we arrive at the Bar Josephine. A name that sounds, to the critical ear, almost too perfect. One could have doubts. One might suspect branding dressed as memory. But in this case, the myth meets the woman. The Bar Josephine—lavish, theatrical, Left Bank to the bone—is rightfully named. Josephine Baker was here. Often. Elegantly. In the years after World War II, when she returned not only as a star, but as a war hero, France’s adopted daughter.

The Lutetia welcomed her, like so many others who had helped liberate the country—and in doing so, elevated its own story. Charles de Gaulle, however, did make history within its walls, spending his wedding night at the Lutetia on April 7, 1921, long before his rise to the presidency. Samuel Beckett, Gertrude Stein, Charlie Chaplin, Henri Matisse were all among its distinguished guests. Over the years, Pablo Picasso, Isadora Duncan, Peggy Guggenheim, and François Truffaut also contributed to the rich cultural tapestry that defines the hotel’s legacy.

Because not every legend is invention. Some are tributes.

And some stories are true. Take Juliette Gréco, for instance—the legendary chanteuse and muse of the existentialists, so intimately connected with the Lutetia. She was reportedly close to tears when, in April 2014, she bid farewell to the hotel before its renovation.

Today, the hotel’s gaze is fixed forward. For the Lutetia history I recommend to visit https://famoushotels.org/hotels/lutetia

And then there’s the pool. It was, after all, legendary — for over a hundred years a social meeting place for Paris’s refined bathers. Today, it has become an elegant spa where only hotel guests can relax, undisturbed by the ordinary bustle of the boulevard. Because, among the most distinguished additions in the recent renovation is the exclusive spa, all facilities including its 17m pool strictly reserved for in-house guests.

Not to forget a particularly exquisite creation: the hotel library. More than a functional reading room, it is a design statement—a tactile celebration of the printed word. Curated under architect Wilmotte’s direction, it houses 2,000 volumes reflecting the hotel's own history and its surrounding arrondissement. Yuval Noah Harari, author of Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks, was recently interviewed there by multiple international television outlets. It is not difficult to see why; the space is a sanctuary of substance.

Not to forget a particularly exquisite creation: the hotel library. More than a functional reading room, it is a design statement—a tactile celebration of the printed word. Curated under architect Wilmotte’s direction, it houses 2,000 volumes reflecting the hotel's own history and its surrounding arrondissement. Yuval Noah Harari, author of Nexus: A Brief History of Information Networks, was recently interviewed there by multiple international television outlets. It is not difficult to see why; the space is a sanctuary of substance.

Privacy, of course, is part of the proposition. With entry-level room rates beginning at €1,500 per night, the Lutetia ensures a deliberate exclusion of the merely curious. This hotel, like many of its calibre, functions as a cultural microclimate—exclusive and immersive. And yet, the ground floor remains in the hands of the Parisian intelligentsia—here, one is human, here, one is allowed to be.

Situated in the heart of Saint-Germain-des-Prés, it is part of the area's vibrant history of artists, philosophers, and writers. Myriam Munnick, Executive Commercial Director, explains: The hotel has always been at the center of this intellectual hub, and we embrace that heritage, offering our guests an immersive experience that reflects the essence of the Left Bank. We are proud to be part of this artistic community and ensure that our offerings align with the creative spirit that defines this area.

The property’s cultural programming remains dynamic. Art and music are integral to its identity. Recent initiatives include a comic-style cocktail menu at Bar Joséphine by Serge Clair—an homage to the visual languages of the 20th century—as well as a photography exhibition by Philippe Carly. The hotel also features permanent works by prominent artists such as Arman, known for his striking sculptures and assemblages; César, a leading figure of the Nouveau Réalisme movement famed for his compressed sculptural forms; Philippe Hiquily, celebrated for his surrealist metal structures; and Mikhaïl Chemiakine, whose expressive pieces often engage with complex social themes. French painter Thierry Bisch has held a permanent artist-in-residence position at the Lutetia.

Strategically, Munnick explains, the future is global: "The hotel is expanding its commercial gaze toward Asia, the Middle East, and the MICE markets of North America. The ambition is to increase occupancy by 10% over the next year."

If Mandarin Oriental can truly weave its deeper brand ethos into the very fabric of the Lutetia, it may well succeed in creating something remarkable. Time will show.

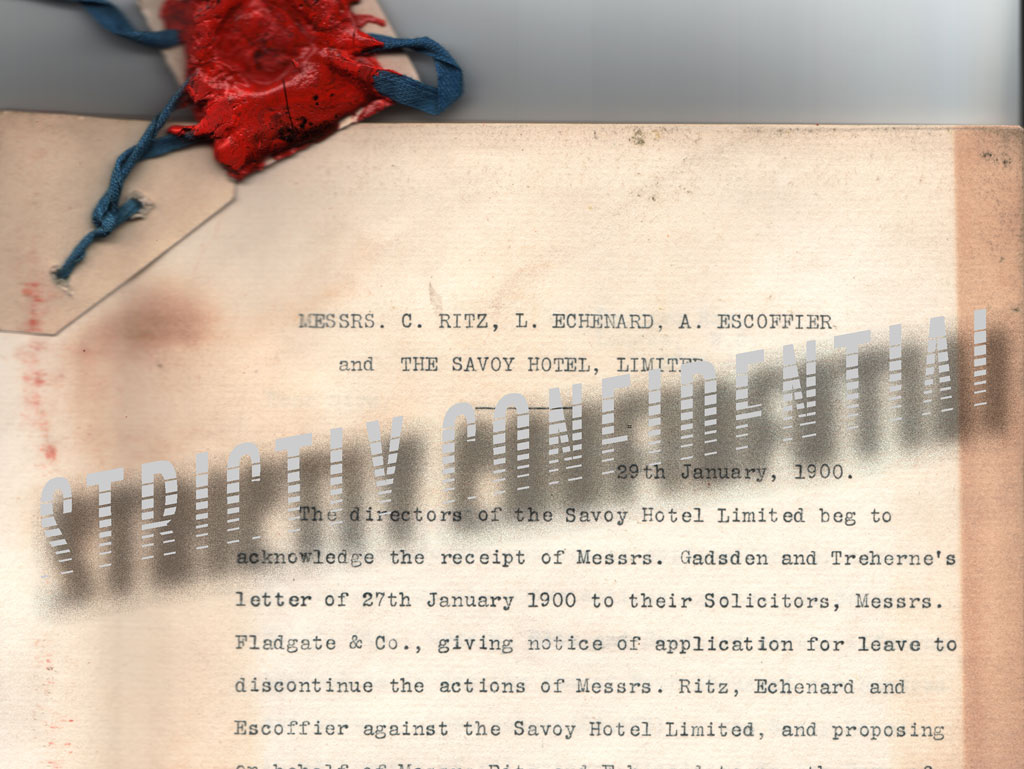

This was no fairy tale wedding

Lutetia and Mandarin Oriental. No princess awakened by a prince. What we’ve witnessed is more akin to two royal houses joining forces, merging their legacies to chart a shared future. At present, the Lutetia is a compelling hybrid—still steeped in Parisian gravitas, now with a whisper of globalism. Mandarin Oriental, meanwhile, is on a shopping spree around the globe. With 42 hotels already in its portfolio—and more to come—one might wonder how many of the world’s great addresses are still left on the market.

At Paris, the Left Bank, adventurous as ever, awaits its next chapter.

Quick Facts

• Rooms and Suites: 184 total, including 47 suites

• Restaurants and Bars: 3 — Brasserie Lutetia, Bar Joséphine, and Bar Aristide

• Spa: Akasha Holistic Wellbeing Centre, exclusively for guests, includes a 17-meter pool, sauna, steam room, fitness area, and six treatment rooms

• Library: 2,000 curated volumes, conceptualized by architect Jean-Michel Wilmotte

• General Manager: Jean-Pierre Trévisan

• Address: 45 Boulevard Raspail, 75006 Paris, France

Famous Hotels Awarded!

( words)

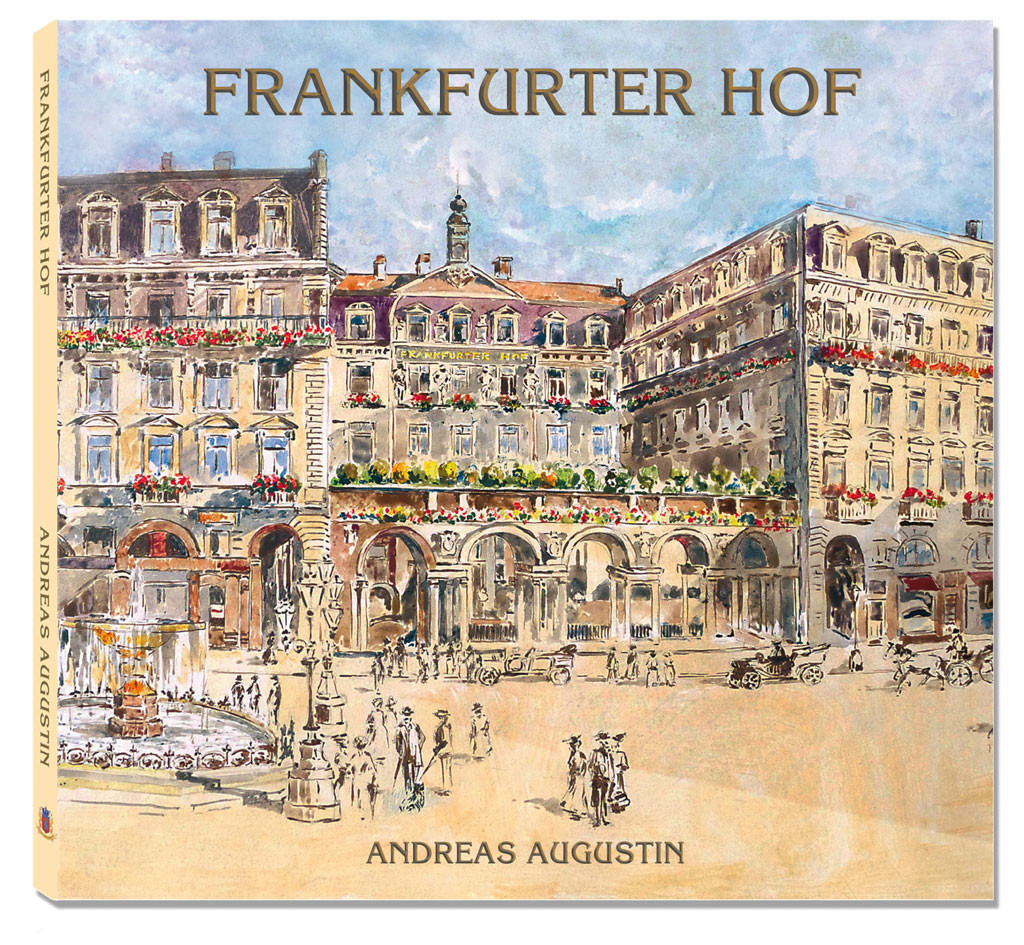

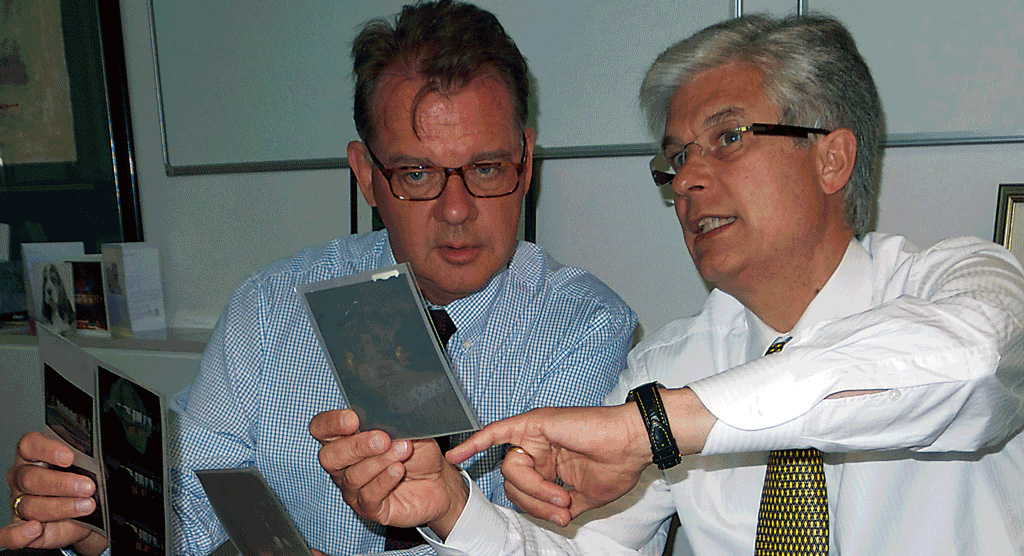

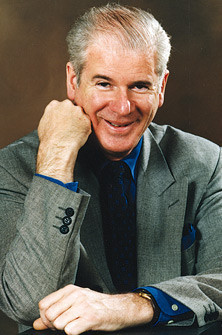

Washington, DC, – Historic Hotels Worldwide® is pleased to announce that the Austrian Hotel Historians Andreas and Carola Augustin have been named the recipients of the Historic Hotels Worldwide® Historian of the Year Award.

“We are honored to recognize Andreas and Carola Augustin for their numerous accomplishments over nearly four decades of academic and scholarly research of the histories of more than four hundred legendary grand hotels,” said Lawrence Horwitz, Executive Vice President Historic Hotels of America and Historic Hotels Worldwide. “They have created the finest library of the stories of hospitality and many of the most famous hotels around the world. They have curated various of the noteworthy “Path of History” permanent exhibitions at famous historic hotels. We have inducted many of the hotels into Historic Hotels Worldwide that have documented histories researched and written by Andreas and Carola Augustin. Their collective work has resulted in the increased awareness and appreciation of the historic significance of these hotels.”

For over 35 years, Andreas and Carola Augustin have used their expertise as researchers and writers to record and make available the histories of the world’s most-famous hotels. The Augustins emphasize historical accuracy. Their research – always uncovering startling new evidence – aims to go beyond superficial exploration to separate fact from fiction.

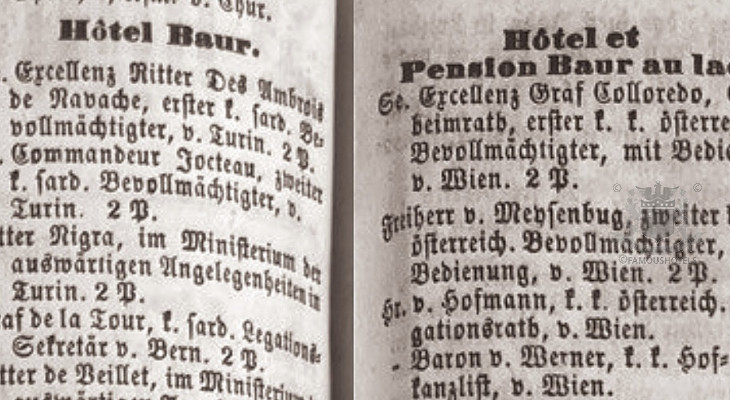

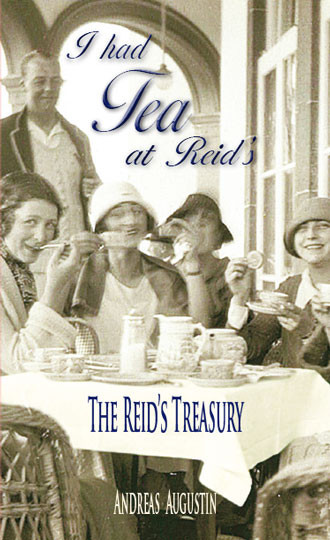

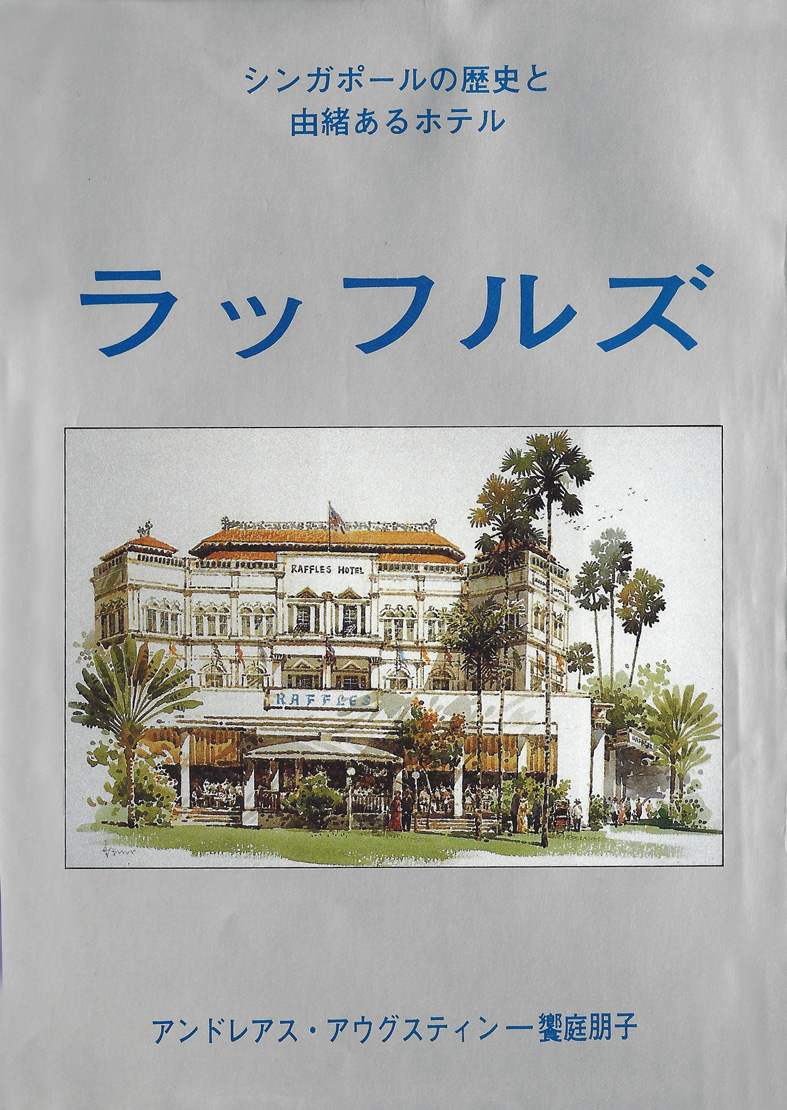

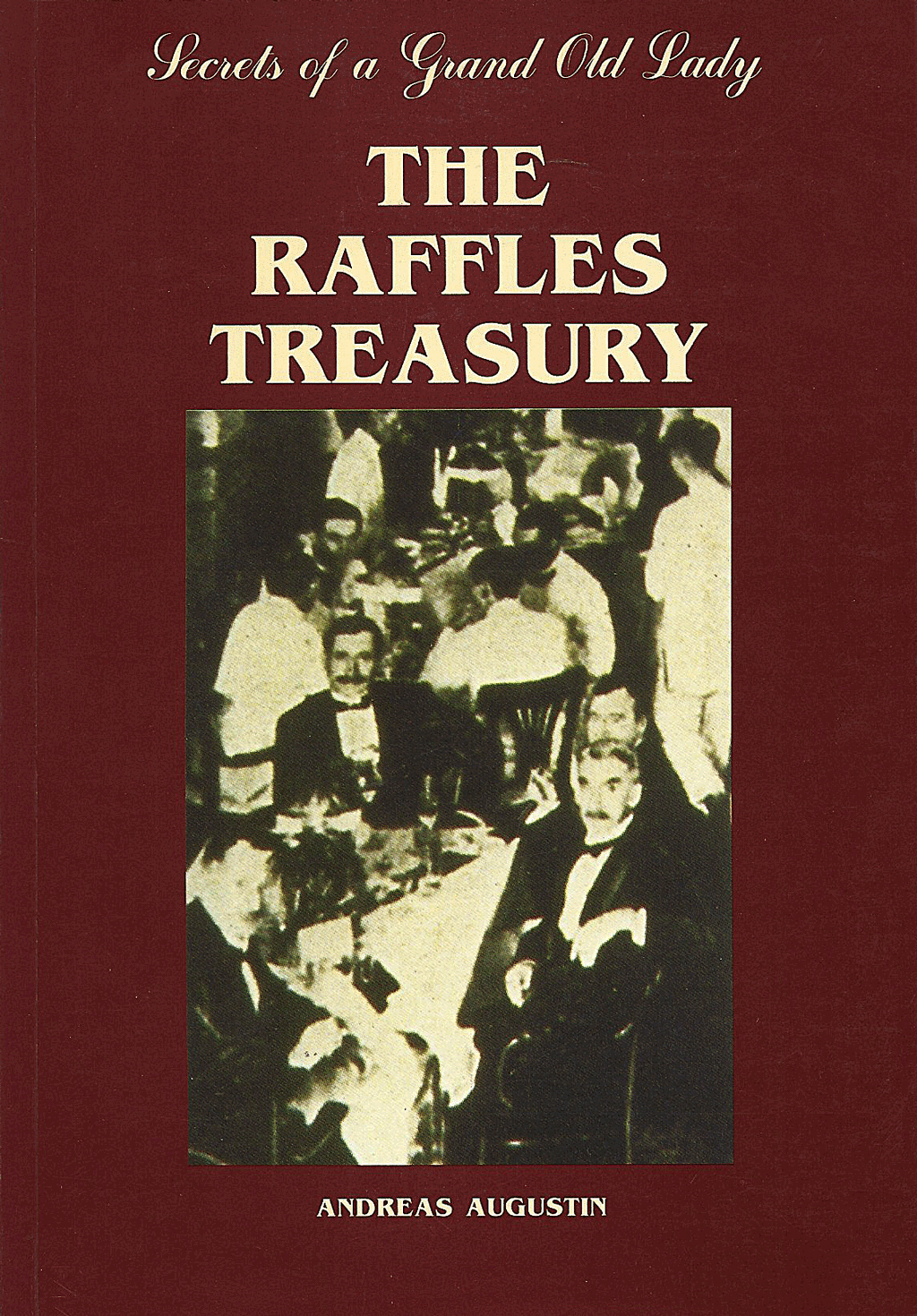

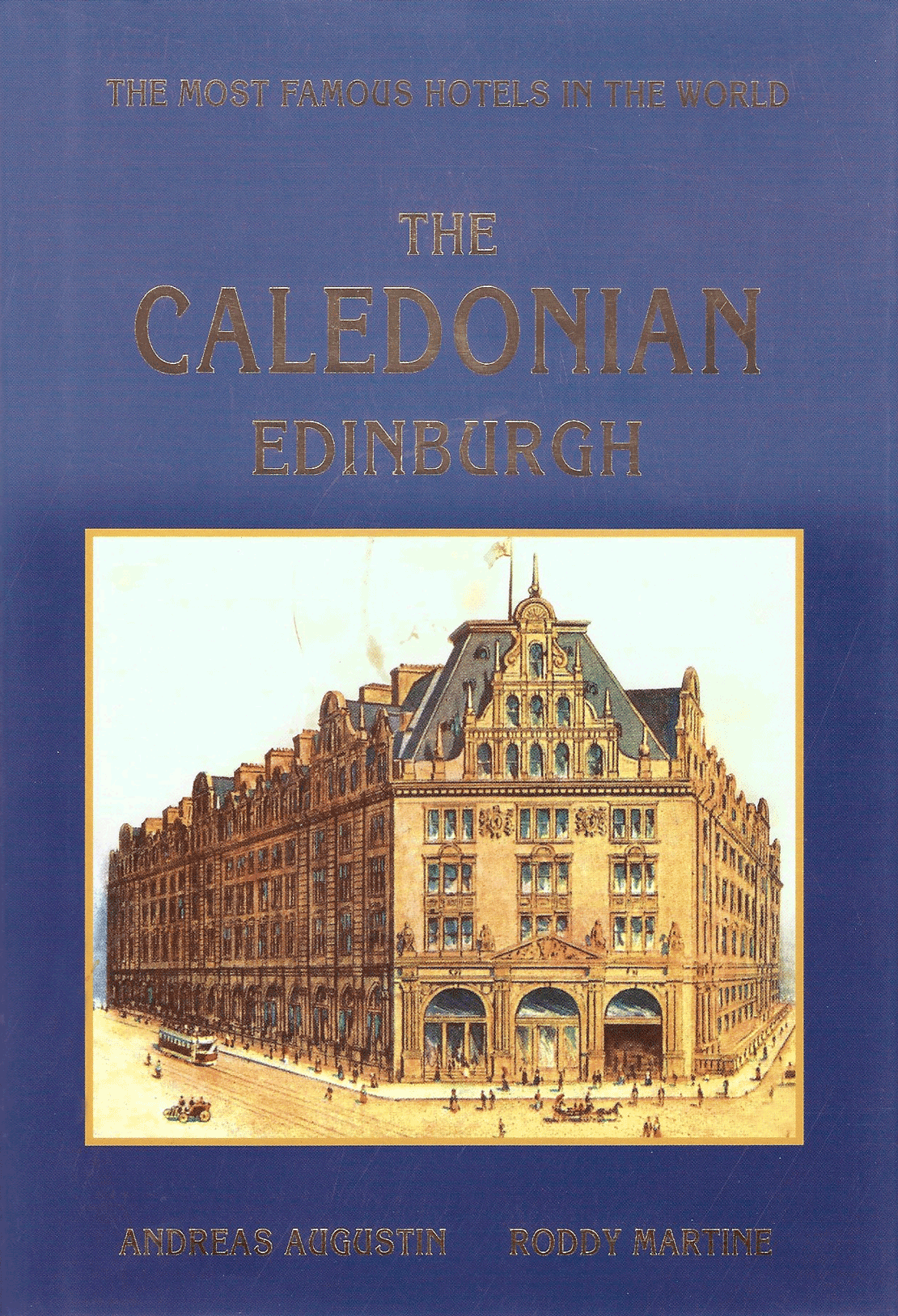

Together, the Augustins have researched and written over 70 books, translated into eight languages, contribute their historical expertise to TV documentaries, manage the public website famoushotels.org as a hotel history resource, and curate hotel history exhibits. Their Path of History permanent exhibitions have become fixtures in some of the most legendary hotels around the world. Together, the couple has researched and documented the histories of over 450 hotels—representing nearly 100 countries.

Andreas and Carola were completely surprised! "This award, after nearly 40 years of voluntary work, is a full validation for us. We are deeply grateful and truly overjoyed. We share this joy with the many wonderful hoteliers who have collaborated with us. A special thanks goes to our team, whose support has been integral to our success. Our children have also been wonderful supporters, discovering hidden treasures in archives more than once. Above all, we must thank our readers, who cherish our books, collect them, and hold them in such high esteem."

Deeply indebted!

The non-profit organisation The Most Famous Hotels in the World was founded in 1986 when Andreas recognised that many historic hotels were in danger of losing valuable historical records. Leading experts such as the late Stanley Turkel—recipient of the Historic Hotels of America® Historian of the Year Award in 2014, 2015, and 2020—were invaluable. Authors and historians have contributed, with special thanks extended to Andy Williamson, Laura Kolbe, Zhang Guangrui, Aruna Dhir, Thomas Cane, Larissa Fortak, Guillermo Reparaz, Roddy Martine, the late Raymond Flower, Marcello La Speranza, Rahel Jung, Adrian Mourby, the late Cherry Chappell, the late Kurt Grobecker, and so many other renowned travel writers who regularly enrich the library on famoushotels.org. World-renowned photographers such as Michelle Chaplow, Heimo Aga, Holger Leue, Bill Lorenz, and others lend famoushotels history books a contemporary yet classic appeal. Artists like Manfred Markowski, Peter Baldinger and Geoffrey Baeverstock have created some fantastic cover paintings. (see THE TEAM)

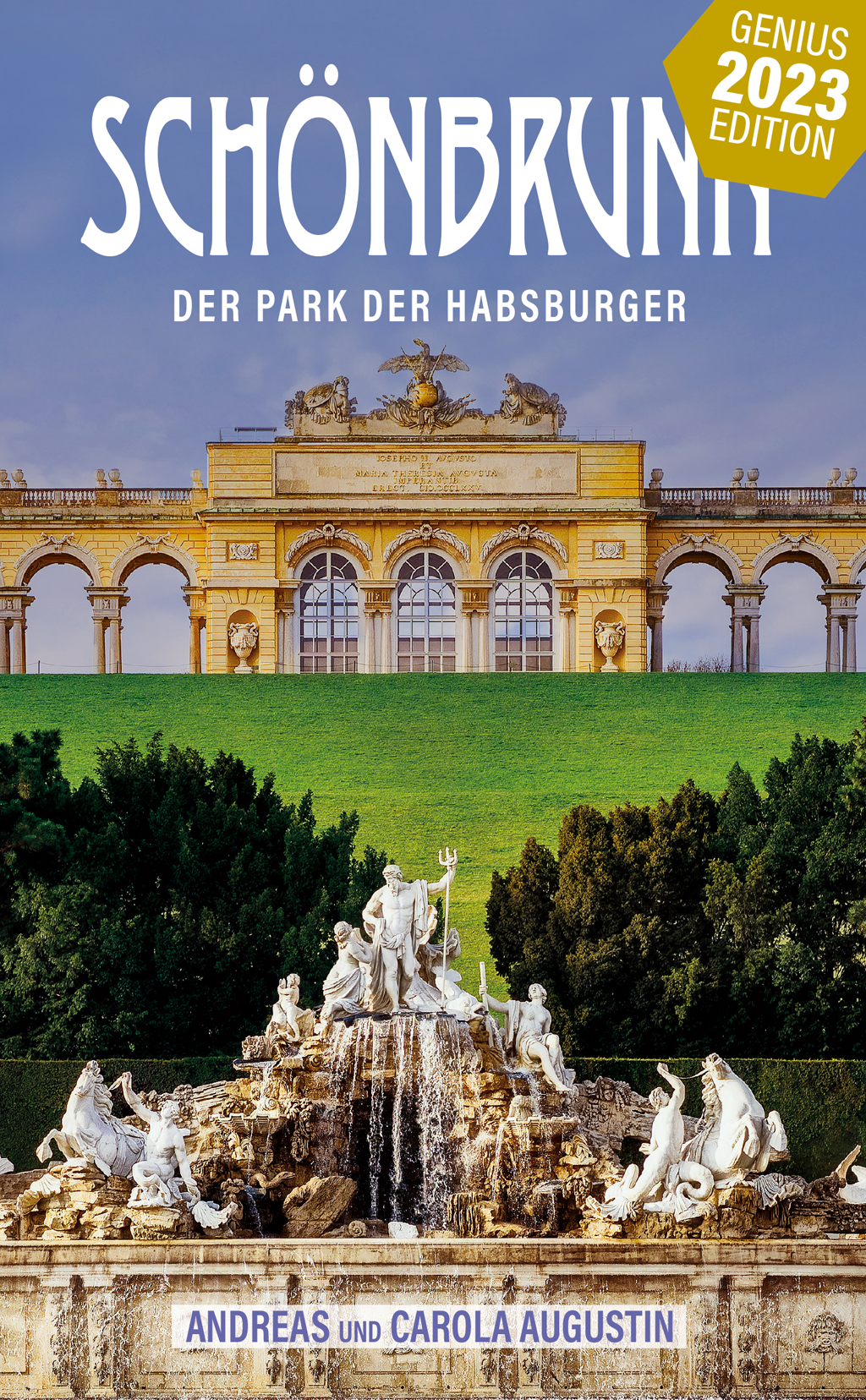

The Augustins are currently preparing the histories of two iconic Raffles hotels—Le Royal in Phnom Penh and the Grand Hotel d’Angkor in Cambodia—as well as the Galle Face Hotel in Colombo, Sri Lanka (1864). Recently appeared a history of Half Moon resort in Jamaica and a book about one of the oldest grand hotels of Europe, Mandarin Oriental Savoy Zurich (1838). In the past years the Augustins visited the war-torn city of Lviv, Ukraine. Despite Russian air attacks, they conducted extensive research into the 1894-opened Grand Hotel, with the help of local historians.

Carola met Andreas in 1986, the year he founded The Most Famous Hotels in The World, and they bonded over their shared passions for travel and hotel histories. Andreas brings his background in journalism and hospitality to the partnership, while Carola, who has a master's degree in history, applies her trained eye to the research. They married in 1989 and have two children.

“She rallies words of encouragement when I am on the verge of despair, unable to find new material. For hours she sits in dark archives, unearthing incredible results. Often, it is the obvious details that escape a casual observer, but her sharp eye catches them,” Andreas Augustin said of his wife and partner. “It is particularly exciting how we keep uncovering new discoveries about these hotels, which we include in each new edition of our books.”

Their goal in all of this is to leave behind a reliable and comprehensive library of hospitality history, safeguarding this knowledge for future generations.

The 2024 Historic Hotels Worldwide® Historian of the Year Award was presented to the Augustins on Thursday, November 21, 2024, at the 2024 Historic Hotels Annual Awards of Excellence Ceremony & Gala, in front of an audience of owners, general managers, senior decision-makers, and guests representing many of the finest historic hotels from around the world. The 2024 Historic Hotels Annual Awards of Excellence Ceremony & Gala took place at The Omni Homestead Resort (1766) in Hot Springs, Virginia, USA. The Omni Homestead Resort was inducted into Historic Hotels of America® as a Charter Member in 1989 and was designated a National Historic Landmark by the U.S. Secretary of the Interior.

About Historic Hotels Worldwide®

Historic Hotels Worldwide®, an official program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation (in the USA), is a prestigious and distinctive collection of historic treasures, including luxury historic hotels built in former castles, chateaus, palaces, academies, haciendas, villas, monasteries, and other historic lodging spanning ten centuries. Historic Hotels Worldwide represents the finest and most distinctive global collection of more than 320 historic hotels in forty-nine countries. Hotels inducted into Historic Hotels Worldwide are authentic historic treasures, demonstrate historic preservation, and celebrate historic significance. Eligibility for induction into Historic Hotels Worldwide is limited to those distinctive historic hotels that adhere to the following criteria: minimum age for the building is 75 years or older; historically relevant as a significant location within a historic district, historically significant landmark, place of a historic event, former home of a famous person, or historic city center; hotel celebrates its history by showcasing memorabilia, artwork, photography, and other examples of its historic significance; recognized by national preservation or heritage buildings organization or located within UNESCO World Heritage Site; and presently used as a historic hotel. For more information, please visit HistoricHotelsWorldwide.com. Historic Hotels Worldwide is affiliated with Historic Hotels of America, a program of the National Trust for Historic Preservation for increasing the recognition of the finest historic hotels in the United States.

Kempinski, Hoteliers since ... when?

( words)

Research in progress / comments welcome

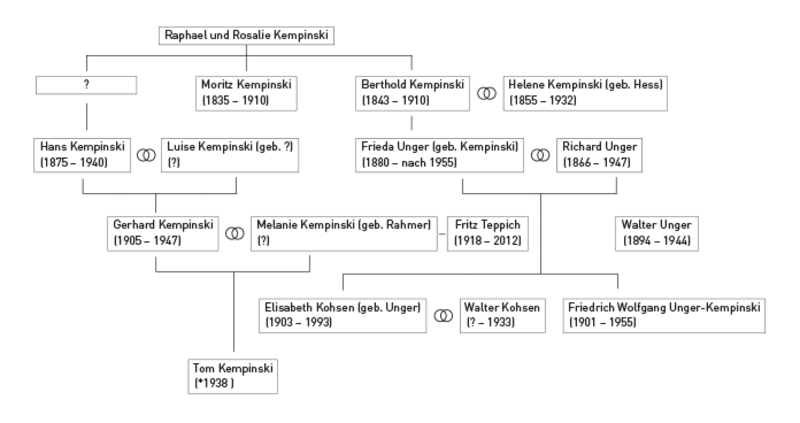

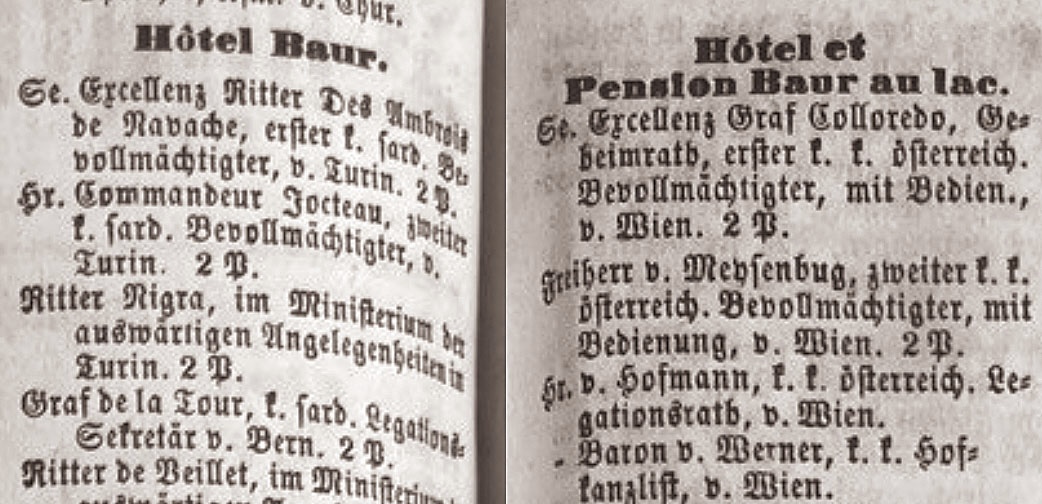

Berthold Kempinski, wine merchant, restaurant owner and entrepreneur, died in 1910, long before his company was “Aryanized” by the Nazis in 1937. In the 1970s, his name was adopted by a Berlin based Hotelbetriebs AG, which has since operated as Kempinski Hotels, managing numerous luxury hotels worldwide. A proof that the Kempinskis are hoteliers since the 19th century is missing.

Berthold Kempinski, wine merchant, restaurant owner and entrepreneur, died in 1910, long before his company was “Aryanized” by the Nazis in 1937. In the 1970s, his name was adopted by a Berlin based Hotelbetriebs AG, which has since operated as Kempinski Hotels, managing numerous luxury hotels worldwide. A proof that the Kempinskis are hoteliers since the 19th century is missing.

Kempinski was a host, not a Hotelier!

At The Most Famous Hotels in the World, we cheer every time a hotel flies its history like a banner. Just make sure it’s not upside down.

The use of the small tagline "Hoteliers since 1897" under the Kempinski logo is causing controversy. What is the famous former flagship of German hospitality doing, and why? In reality, the Kempinskis — owners of various Berlin restaurants — were never hoteliers. After over 50 yeares of successfully operating various restaurants and a wine trade, being Jewish, they were expropriated, persecuted, and murdered by the Nazi regime. Today, the Kempinski hotel group claims to prove that they have been "hoteliers since 1897," but this information lacks any historical basis. Here are the facts:

The Wine Tavern:

The Kempinski era began with a determined Jew named Bertold Kempinski from Breslau (now in western Poland), who set out to conquer the soul of the capital of the German Empire, Berlin. And he had a hunch that this soul lay in the stomach. Around 1870, he opened a wine shop at Friedrichstraße 178, which was officially registered in the commercial register in 1872. The wine tavern, operated with his wife Helen, proved to be a lucrative source of income providing the Kempinskis with capital. The place soon became too small and having achieved a secure level of prosperity they bought real estate at Leipziger Strasse.

The "Weinhaus Kempinski" soon became an institution. But we must not imagine it as a modest tavern—it had a distinct social character, lively and popular in every respect. At the height of the Bertold Kempinski era, the press celebrated:

"7,200 guests and 20,000 oysters daily—caviar for the people—wine cellars—bakery and laundry—hygienic facilities—not a single table empty!"

Despite this success, Kempinski and his wife Helen remained grounded. Alongside roasts and sausages, they served oysters, crabs, caviar, woodcocks, even lapwing eggs—affordable for everyone. It gets even more astonishing: for his scattered wine cellars across Berlin, he paid an annual rent of 30,000 marks. He ran his own bakery and laundry, a facility for silver-plating tableware, and a porcelain painting workshop where plain factory-purchased porcelain was decorated and glasses were adorned with gold rims.

On peak days, the bakery produced up to 17,000 bread rolls, while the laundry processed up to 20,000 freshly washed and ironed napkins. These did not only supply his own restaurant but also many other establishments, which—an innovation at the time—rented table linens. A bottle-washing facility cleaned 10,000 bottles daily, and a dedicated waste incineration plant was installed.

From a social perspective, Kempinski must also be highlighted: he maintained an emergency accident and medical station. The common practice of reusing food scraps was eliminated by the principle that once food left the kitchen, it was not allowed to return. Some kitchen waste was turned into soap, some was used as animal feed, and some was sold to chemical factories, bringing in an additional 20,000 marks annually.

He is said to have once joked: "You will find the president of the Reichstag and deputies from all parties here, just as you will find a young man dipping into his pocket money. But one thing you will never find: an empty table."

Moritz Kempinski (1835-1910); his younger brother, Bertold (1843-1910) and wife Helen Kempinski.

Berthold Kempinski's honorary grave is located in Field T2 at the Jewish Cemetery in Berlin-Weißensee.

The Unger Era:

The Kempinskis had no male heir. For this reason, their son-in-law, Richard Unger, the husband of their daughter Frieda, and a nephew, Hans Kempinski, joined the company. The artistically inclined Hans was a passionate painter, but Unger proved to be a skilled businessman. Bertold Kempinski retired, enjoying his well-earned rest, and passed away in 1910. By the time of the First World War (1914–1918), Unger, who now owned the business, had managed to build a respectable real estate complex around the company. He expanded it into a large-scale gastronomic enterprise.

Kempinski family tree

Ku’damm 27

As the area around Kurfürstendamm grew increasingly popular, Unger purchased and operated a restaurant at Ku’damm 27 (Kurfürstendamm 27). In 1928, he took over the management of Haus Vaterland at Potsdamer Platz and introduced a groundbreaking new restaurant concept—an entertainment dining experience unlike anything Berlin had ever seen.

Spread across four floors, exquisite delicacies were served, complemented by artistic performances. Kempinski became renowned far beyond Berlin, much like Sacher for Vienna or Sprüngli for Zurich—his name became a synonym for fine dining. When the Great Depression reached Germany in December 1929, the lavish oyster selection at Kempinski was still praised, offering guests a way to pass the time before the promised Porterhouse steak for five to six people arrived within 30 minutes, as stated on the menu.

However, it is important to note: despite its fame and scale, Kempinski was still only a restaurant—not a hotel! In 1932, Unger made an excursion into the hotel business by operating Schloss Marquardt near Potsdam. In 1932, the family leased and operated Schloss Marquardt as a hotel, but it did not carry the Kempinski name. It was simply a property managed by the family—an early and singular step into hospitality, without branding it as such. It was a brief chapter in an otherwise culinary-focused history. The hotel was not called “Kempinski.” The true rise of Kempinski as a hotel brand came two decades later.

Nazi Regime:

During the Nazi regime and World War 2 (1930s–1945) the jewish Kempinski business under Unger came to an abrupt halt. Richard Unger and his wife emigrated to the United States. Under the pressure of the anti-jewish racial laws, the Kempinski enterprise was in fact stolen by the German Reich, which constituted a typical act of 'aryanization', as these acts of expropriation were called. Walter Unger, son of Richard, had remained in Germany to continue the business. Eventually, he had been forced to transfer the shares of his family's company to a company called Aschinger AG, all this in exchange for his own life. After the deal was executed, Walter Unger was murdered at the concentration camp Auschwitz. Even the jewish name Kempinski was no longer accepted by the regime. The restaurant(s) were renamed F.W. Borchard.

After World War 2:

After 1945 (end of World War 2), Bertold Kempinski's grand son Friedrich W. Unger had been able to restitute the location of Kurfürstendamm 27 from the Aschinger company who had bought it for a ridiculous low sum it in 1937.

Hotel rooms were scarce after the war. Supported by the Marshall Plan, the construction of a hotel was approved. In February 1951, in the presence of Berlin's Governing Mayor, Dr. Walther Schreiber, the foundation stone for a hotel was laid on Kurfürstendamm plot number 27. The hotel opened in 1952. It was to become the first Kempinski.

For the first time, the name Kempinski—previously associated with the successful restaurant chain before World War II—adorned a hotel in a prime location in West Berlin. Unger sold his shares. According to various sources, he failed to share the profits with the other members of the Kempinski family.*)

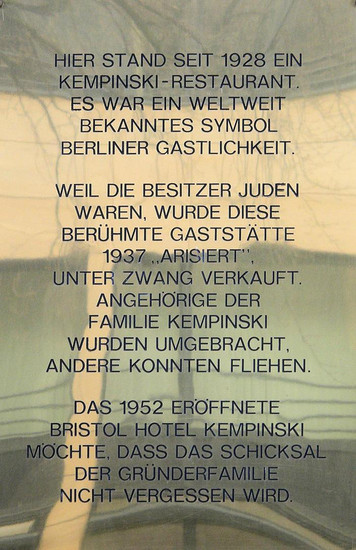

In 1994, after lengthy discussions, a memorial plate was unveilde at the Kempinski Bristol in Berlin. To claim that Kempinski has been hoteliers since 1897 is simply audacious. Let us take to heart what is written on the commemorative plaque at the hotel:

HERE STOOD A KEMPINSKI RESTAURANT SINCE 1928.

IT WAS A WORLD-RENOWNED SYMBOL OF BERLIN HOSPITALITY.

BECAUSE ITS OWNERS WERE JEWISH, THIS FAMOUS ESTABLISHMENT WAS "ARIANIZED" IN 1937 AND FORCIBLY SOLD.

MEMBERS OF THE KEMPINSKI FAMILY WERE MURDERED, WHILE OTHERS MANAGED TO ESCAPE.

THE BRISTOL HOTEL KEMPINSKI, OPENED IN 1952, WISHES TO ENSURE THAT THE FATE OF THE FOUNDING FAMILY IS NOT FORGOTTEN.

Hoteliers since 1897 ...?

In 2010, Kempinski, under its president Reto Wittwer, added the line "Hoteliers since 1897" to the company's name. For the first time ever the date 1897 had been circulated. It looked like an attempt to create a legend.

It takes just a small trick to come up with a much better and historically approved tagline

In the Munich commercial register Kempinski Aktiengesellschaft (it is no longer listed in Berlin) is registered with its headquarters, branch, and domestic business address at Maximilianstr. 17, 80539 Munich (Hotel Vier Jahreszeiten Kempinski Munich). The date of the first statutes is recorded as April 5, 1897, which at best creates the illusion of historical continuity.**

In reality, a "hotel operating company" in Berlin adopted the Kempinski name in the 1970s. This is still far from "Kempinski – Hoteliers since 1897." Out of respect for history-conscious consumers, it would be only fair to clarify this misleading claim.

Why doesn’t Kempinski use "Hospitable" — or "At Your Service since 1872" instead? With a bit of imagination and verifiable facts, they could rightfully make that claim, referencing their origins in the wine trade.

* There is information available on the web concerning the dubious 1950s-deals, involving the former aryanization-company Aschinger AG, which continued to be involved via sub-companies even in modern Germany. Names featured among others are Paul Spethmann and Werner Steinke (sources: Fritz Teppich and others), who were former Nazis, still acting in the same positions after the war.

For example: //hagalil.com/archiv/98/08/kempinski.htm

Book about the saga of the Kempinski family: //berlinerliteraturkritik.de/detailseite/artikel/die-familiensaga-der-hoteldynastie-kempinski.html?type=1&cHash=eabf4ee4fba3ae5aeb8a5e126d102547

** Kempinski’s grand son Friedrich W. Unger merged his share of the business with a Hotel Corporation called Bristol and Kaiserhof. Thus the company acquired the name Bristol. The Bristol was a hotel located Unter den Linden, in a different part of the city. It had opened for business in 1890. A 'Hotelbetriebs-Aktiengesellschaft', registered in 1897, had acquired it in 1904. Before 1952, that hotel Bristol had nothing in common with the Kempinski Bristol Berlin.

Hotels lost in History

( words)

Austria

- Grand Hotel Europa Innsbruck used to be regularly in the social limelight of the Tyrolean provincial capital in the heart of Innsbruck. Its Baroque Hall from 1883 was the chosen venue for functions of all kind. Bavaria's King Ludwig II described the 5-star hotel as "the most beautiful place in Innsbruck to celebrate festive events". King Karl Gustav of Sweden found in the suites of the Grand Hotel the necessary rest and relaxation between the competition of the two Olympic Winter Games from 1964 and 1976. In 2007, the Italian "Palenca Luxury Hotels" acquired Innsbruck's most important hotel. Extensive renovation and expansion works - which have already been completed in the lobby, bar and reception area - followed in 2008/09. In 2020, the hotel closed and auctioned its inventory.

- Hotel Metropole, Vienna, opened 1873; by architects K Schumann und L Tischler, famous before the war, infamous headquater of the GESTAPO during 1939–1945, destroyed by bombs in 1945, never rebuilt.

-

Hotel Continental, Vienna, opened 1873, is today's Sofitel Vienna - a very chic modern architecture with interesting features. Destroyed in 1945 during the battle for Vienna, between Germany's army and Russian forces. Dating back to 1591 as a coach inn "Zum goldenen Lamm" and an other part used to be the hotel "Zum weißen Schwan", merged into "Hotel Continental" for the world expo in 1873 (with 200 rooms, large ball room for 600 pax and one coffee house).

- Hotel National, Vienna; built 1848, dating back to 1687 (original name of the inn: Zum goldenen Ochsen) - picture below.

Hotel National, Vienna Architects: Ludwig Förster, Theophil Hansen. By 2017 an apartment building facing either renovation or demolition.

- Bad Ischl: Tallachini’s Grand Hotel, where Princess Sisi (later Empress Elisabeth) accepted Emperor Franz Josef’s proposal of marriage, was later renamed the Hotel Kaiserin Elisabeth and is now the Residenz Elisabeth. In Summer 1908, it hosted HRH Edward, the Prince of Wales.

- Semmering: Südbahnhotel — elegant resort of the Austrian-Hungarian empire, gathering place during the 1930s, and again in the 1950s. Lost momentum as entire region was abandoned in favour of more attractive tourism destinations. Stands as a testimonial to uncreative tourism and region management in Lower Austria, commanding a stunning view over the Semmering mountains.

Bahamas

- Nassau: Royal Victoria. The first luxury hotel in the Bahamas, built in 1861 and closed in 1971. The abandoned building sat vacant for years, gradually being stripped, until it burned down in the mid-1990's. A parking lot replaced it. The sprawling gardens of the hotel remain, however. Link to photographs here.

Chile

-

Carrera, Santiago de Chile: since 1940, its opening year, the hotel was originally a luxury apartment building, and designed to be part of the new Civic Center. 1940s-60s: The guest list included a mix of socialites, jet-setters and celebrities. 1985: Pro-democracy guerillas attempted to blow up Pincohet's office from one of the most desirable rooms in the hotel (see Legendary Stories). 2001: Hoteles Carrera increased its capital through the issue of 5,358,920 shares equivalent to US$6.2mil. In December 2004 the hotel closed for conversion to government offices.

China

- Macau, Hotel Bela Vista

-

Beijing Hotel (Huafeng), Beijing

1880s-1900: The Compagnie des Wagons-Lits built hotels like the Ghezireh Palace in Cairo, the Pera Palace in Constantinople, the Hôtel de la Plage in Ostend (Belgium), the Hôtels Terminus in Bordeaux and Marseille, and the Riviera Palace in Monte-Carlo. 1900: The foundation stones of the hotel were laid 1905: The company opens the Grand Hôtel des Wagons-Lits in Peking. The only hotel in the Legation Quarter, it was to accommodate travellers from Europe on the Trans-Siberian Express. A 1930s guidebook says the original building stood in a large garden ornamented by stone fishponds, sole relics of ancient imperial offices. 1915: The hotel's five-story red brick building was completed. Later known as the 'old building', this structure brought the hotel very brisk business. 1917: Prospering with good management and the booming tourism industry, the hotel received an investment boost of two million silver coins which added a seven-story French-style building (today's Building B). This new structure, which is now called the 'middle building', consisted of 105 suites furnished with central heating, telephone and toilet facilities, dining halls and kitchens, a hair saloon and a ballroom with a sprung floor. Otis brand elevators took guests to the bar and open-air terrace for dancing on the seventh floor. Foreign guests described it as the number one luxury hotel in the Far East. Its opening was attended by well over 800 distinguished guests who packed the lobby and dining halls. 1920s: The Thomas Cook Travel Agency set up an office in the hotel and rented the liner Franconia to ferry tourists to China. In those days, a model of the ship was displayed in the Western dining hall and a banquet with dancing would be thrown around the model for each group of new arrivals. 1922: The Hong Kong Hotel Company acquired 85 percent of the Shanghai Hotels Limited, which held 60 percent of the share capital of the Grand Hôtel des Wagons-Lits. 1937: The '1937 Incident' when Japan invaded China triggered a slump in business. The hotel was taken over by the Japanese during their occupation of Beijing. 1945: After World War II, the hotel was taken over by the municipal government of the Kuomingtang, after the war. Its business remained slack for the instability of society and the lack of foreign tourists. 1949: The People's Republic of China named Beijing its capital and offered the hotel a new lease of life. State and Diplomatic functions had to be held in a place with Chinese characteristics and high popularity 1954: Completion of a new wing. 1974: The old brick building was pulled down and a new 89-metre structure put in place. At the time it was the highest building in Beijing.

Egypt

- Cairo: Shepards — burnt down

- Continental-Savoy (Cairo), still standing, but empty

England

London

- Hotel Cecil, built in 1896, a large hotel in the Strand in London, England. It was named for Cecil House, a mansion that had occupied the same site in the 17th century. Designed by architects Perry & Reed in a "Wrenaissance" style, the hotel was the largest in Europe when it opened with more than 800 rooms. The proprietor later went bankrupt and was sentenced to 14 years in prison. The Cecil was largely demolished in Autumn 1930, and Shell Mex House was built on the site. The Strand facade of the hotel remains, with, at its centre, a grandiose arch leading to Shell Mex House proper.

- The Grand Hotel (we have reasons to believe that it was the first in the world by this name) had opened in January 1774 (by David Low), but ceased to exist in the 1880s.

- Basil Street Hotel was an oasis of English charm, run by the same family for 3 or 4 generations, just behind Harrods. Beloved of the hunting, shooting fishing set, and home to the famous Parrot Club it closed around 2005 to be stripped and turned into offices. The collection of antiques furnishing the hotel collected by the family took days to sell.

-

Grillon’s Hotel

-

Pulteney Hotel

-

To celebrate the defeat of Napoleon at the Prince Regent’s Grand Jubilee celebration in 1814, while Napoleon sailed for Elba, France’s King Louis XVIII took rooms at Grillon’s Hotel on Albemarle Street. Another popular hotel among foreign royals staying in London was the Pulteney Hotel, named after Pulteney, Earl of Bath, who had resided in the building before it became a hotel. It was located on the west corner of Bolton Street at 105 Piccadilly.

-

France

Nice

-

Excelsior Regina: today appartements; built in between 1895 and 1897 as a hotel for the royal faces and for the rich aristocracy who used to visit Nice in the late 19th century, the Excelsior Regina Palace is at present an apartment building which has lost nothing of its past architectural splendor. It is located in the hilly and tranquil Cimiez. The history of the construction of the Excelsior Regina Palace is related to the name of Queen Victoria of England who promised she would visit the French Riviera more often provided that a royal residence to match her reputation was built.

The building bristles with decorative elements characteristic of the Belle Epoque period. Lush bas-reliefs, glass marquees, picturesque attics and oriels peg out the white façade of the building. Parts of the Excelsior Regina Palace and the garden stretching in front of it, including the marble statute which depicts Queen Victoria (a monument placed at one of the garden entrances) enjoy the statute of historical monument. They were listed as such in 1992. Source: [url=http://www.nice-tourism.com/en/nice-attractions/historical-edifices-and-landmarks-in-nice/excelsior-regina-palace.html]http://www.nice-tourism.com/en/nice-attractions/historical-edifices-and-landmarks-in-nice/excelsior-regina-palace.html[/url]

Beaulieu sur Mer

-

Bristol Palace: True architectural masterpiece of the Belle Epoque, the Rotonde de Beaulieu rises in front of the sea and catches the eye of the passers-by and visitors of the town. Large circular room with glass-faced apses and a cupola with cut-off sides, the Rotonde is a former outbuilding of the Hotel Bristol, built between 1899 and January 1904 at the request of the British clientele of the palace to serve tea. This lounge was built in the south continuation of the building by the same architect, the Danish Hans-Georg Tersling. The Hotel Bristol, financed by a London furniture manufacturer, Sir John Blundell Maple, was built in record time, like many palaces on the Riviera during the Belle Epoque, between February 1897 and December 16, 1898. Inaugurated on January 5, 1899, the palace comprises 300 luxuriously equipped rooms, including bathrooms fed with heated sea water, spread over 5 floors with 60 rooms per floor. The building has high roofs evoking the style of an English castle. On March 28th 1911, in the evening, fanned by a strong wind, a fire broke out in a chimney and spread to the top two floors of the building and to its entire cover. Following the intervention of the firemen of Beaulieu and Nice and of the Chasseurs Alpins, the fire is mastered by flooding the upper floors. Thanks to the reinforced cement structure of the building, the lower part of the building remains relatively intact, the fire reducing the upper two floors to nothing.

The rest of the hotel is quickly rehabilitated and the Bristol reopens for the winter season of 1911-1912, amputated from the destroyed floors and with a classic roof in red tiles with a slight slope. Converted into a high-end condominium by the promoter Saglia in 1954, the Bristol loses part of its gardens as well as the tennis courts, ceded to the municipality of Beaulieu. The building retains its original appearance, decoration and part of the lobby. La Rotonde was for his part neglected and left without maintenance, threatened with demolition and finally expropriated for the benefit of the municipality in the 1970s. Transformed into a conference center in 1982 and operated by the Partouche group, it will not be any more used from 2001. Again abandoned during 10 years, it now shelters, since October 2011, the Salons de la Rotonde Lenôtre and took back its festive vocation and initial receptive. -

source: http://www.agencebristol.com/en/news/the-bristol-and-the-rotonde

Germany

Leipzig

- Hotel de Prusse (1805-1905), Hotel Preussischer Hof (1905-1921)

- Bühlerhöhe: Schlosshotel Buehlerhoehe (Bühlerhöhe): officers home since 1918; luxury hotel between 1986 and September 2010. Closed due to low business.

-

Pflaums Posthotel Pegnitz: An inn that perfectly illustrates the European tradition of a single family`s involvement in a highly personal business over centuries. Pflaums Posthotel Pegnitz, opened in 1707, was owned and run by the founding familiy for 11 generations. As the inn is only 19miles from Bayreuth, it was filled with celebrities during the music festival, and trough much of the rest of the year as well. The 5 star superior rated property has two award winning restaurants 'and 'Outdoor Dining'; . Golf, Spa and conference facilities for incentives and small meetings, Open All Year. Hotel of the Year Germany. Grand Award and Golden Key for Interior Design. New York. Designer Magazine and American Hotel and Restaurant As. 1707 opened under the name Gasthof Post Schwarzer Adler by Heinrich Friedrich Pflaum (with five rooms) Recently a boutique design and arts hotel with ony 25 individually designed rooms, run by Hermann Pflaum, one of the leading chefs of Europe. It closed in 2016.

Hongkong

- Hong Kong Hotel — the "mother" of the Hong Kong – Shanghai Hotels company

- Repulse Bay Hotel, one of the last remaining colonial style buildings in Hongkong until it was demolished to give room for a high rise apartment building ca. 1985. It had a huge balcoly with a view of the South China Sea and was an important part of Hongkong history when it was torn down. The veranda is said to have been rebuildt somehow, but the old atmosphere must be gone forever.

Hungary

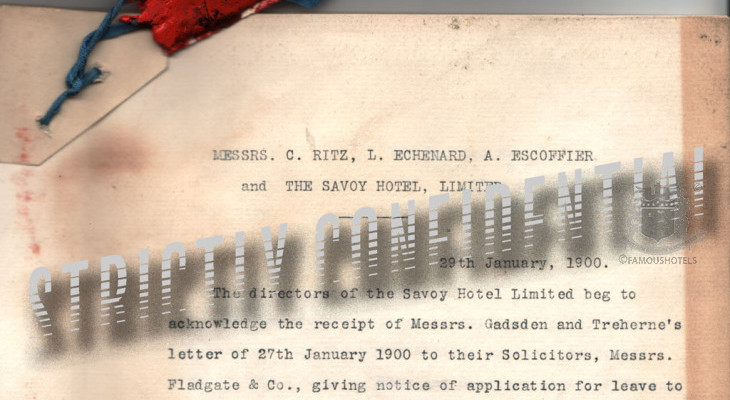

Budapest — Hotel Ritz — one of the "Ritz" franchise projects —it opened in 1913 with 120 suites, a reading room, a reception and banquet hall, a winter- and a rooftop-garden, a café, a restaurant, a bar, a barbecue room, central heating, three passenger and four service lifts. Despite the professional management of Károly Vásárhelyi, in 1916, the luxury hotel went bankrupt in the recession due to the First World War.

Budapest — Hotel Ritz — one of the "Ritz" franchise projects —it opened in 1913 with 120 suites, a reading room, a reception and banquet hall, a winter- and a rooftop-garden, a café, a restaurant, a bar, a barbecue room, central heating, three passenger and four service lifts. Despite the professional management of Károly Vásárhelyi, in 1916, the luxury hotel went bankrupt in the recession due to the First World War.

In 1913, Mrs César Ritz, Marie, personally supervised the opening. It was reopend as Duna Palota (Danube Palace). On January 15, 1945, the hotel was bombed and finally flushed for several days. The ruins were removed in 1947. From 1981, the Hotel Forum (now InterContinental Budapest) stands in its place.

India

- Calcutta Great Eastern built by David Wilson in 1841 Spence's by John Spence, before 1830 Grand, by Stephen Arathoon, opened in 1911, closed in 1937.

Indonesia:

- Hotel des Indes was one of the oldest and most prestigious hotels in Asia. Located in Batavia (now Jakarta), in the Dutch East Indies (now Indonesia). The hotel had accommodated countless famous patrons throughout its existence from 1829 to 1971. Before being named Hotel des Indes, a name suggested by the writer Multatuli, it was named ‘Hotel de Provence’ by its first French owner and for a short spell went by the name ‘Hotel Rotterdam’. After Indonesian independence it was renamed ‘Hotel Duta Indonesia’, until it was demolished to make way for a shopping mall. >>> This hotel should not be confused with ‘Hotel des Indes’ in The Hague, the Netherlands. Details on wikipedia.

Italy

Venice:

- The Grand Hotel des Bains was one of the famous hotels on the Lido of Venice. Built in 1900 to attract wealthy tourists, it is remembered amongst other things for Thomas Mann's stay there in 1911, which inspired his novella Death in Venice. Luchino Visconti's film of the novel was shot there in 1971. The hotel was also used as Shepheard's Hotel in Cairo in the 1996 film The English Patient; Diaghilev died at the hotel in 1929. Until 2010 the hotel was frequented by movie stars during the Venice Biennale. In 2010, the hotel was closed to be converted into a luxury apartment complex, the Des Bains residences. As of September 2017 the hotel is still awaiting renovation. A large fence surrounds it, with a guard employed inside.

- Rifugio Guglielmina / Ricovero al Col d’Olen It was 1878 when Ricovero al Col d’Olen was first inaugurated: it was the third among the 8 hotels founded, or run, by the Guglielmina family between the last half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth century. Giuseppe Guglielmina was a humble shoemaker from Mollia: the reason for the fast growth of its hotel business can be find in the entrepreneurial spirit of many public figures of the time as well as in the atmosphere of openness to tourism which followed the conquest of Monte Rosa. As a matter of fact, only eight years after the rise to Signalkuppe (today named Punta Gnifetti), Giuseppe Guglielmina and his family were able to run the Albergo del Monte Rosa, inaugurated in Alagna in 1850 and which was later expanded; then, they managed to run the Albergo delle Alpi in Riva Valdobbia in 1871, the Ricovero del Col d’Olen in 1878, the Albergo d’Italia in Varallo Sesia in 1879, the Albergo del Mottarone on the Maggiore lake in 1884, the Hotel Bellevue Alpino in Gignese in 1900, the Hoten Royal in Ospedaletti Ligure in 1901 and the Grand Hotel Eden in Santa Margherita Ligure in 1090. Moreover, the newspaper of the time record their presence even in Sicily, in Palermo, where they ran the Ristorante Cafè Chantant on the occasion of the Universal Exposition in 1981. Unfortunately Rifugio Guglielmina has been completely burned down. The fire started in the early morning of 22 December 2011 and couldn't be stopped because of strong wind, that did not allowed firemen to reach Col d'Olen.

Japan

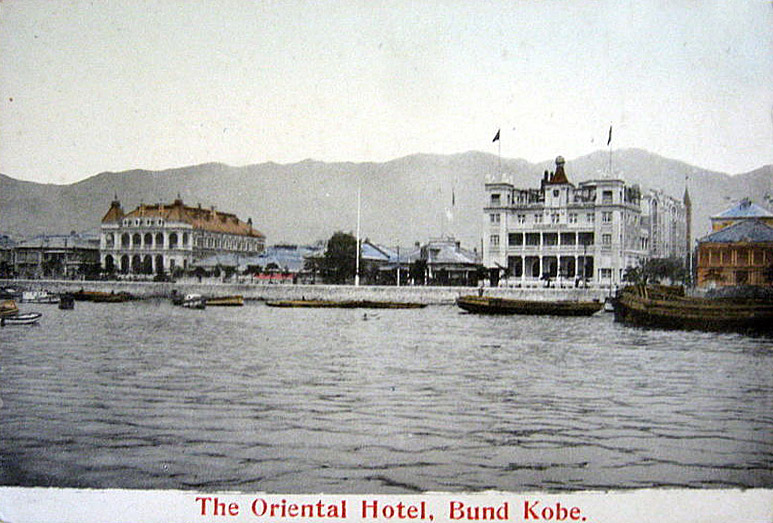

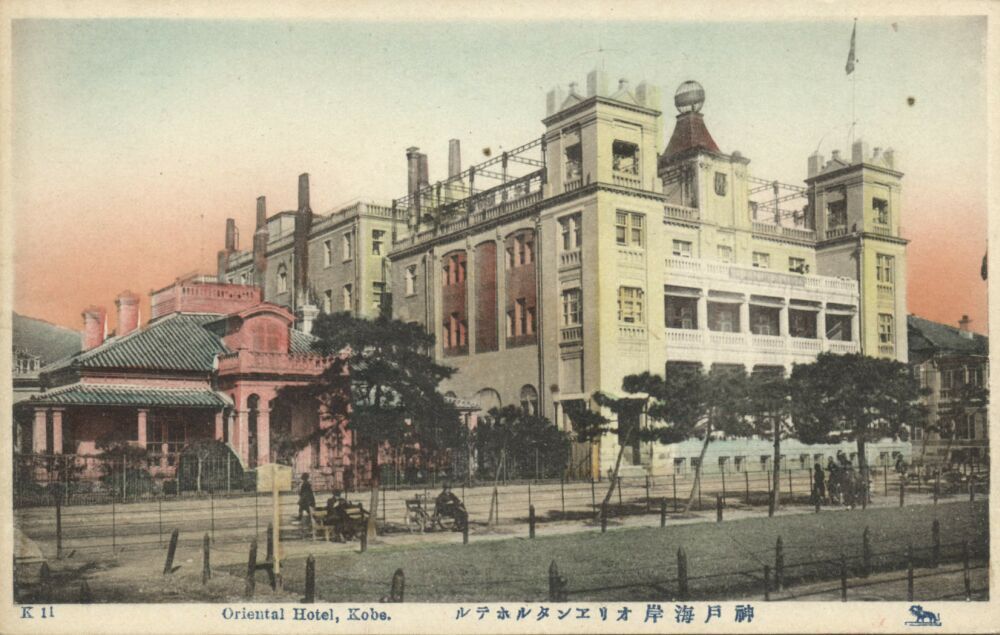

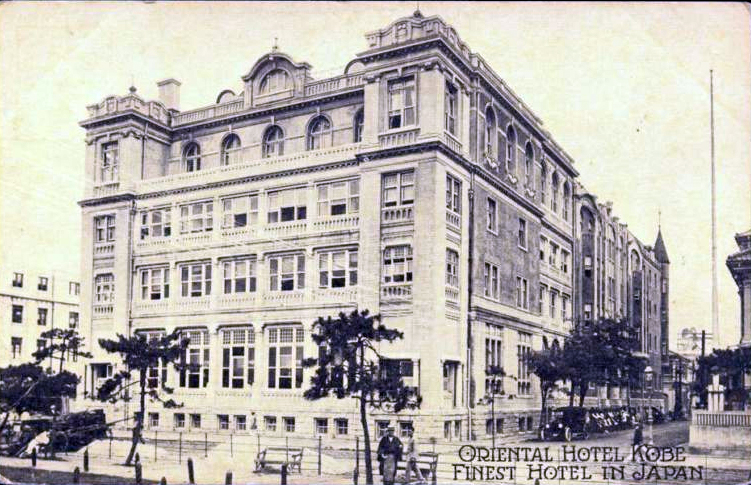

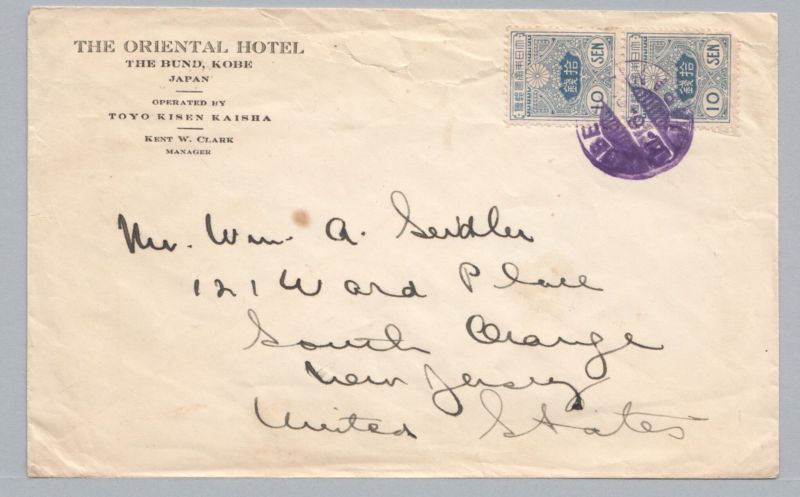

- Kobe

The Tor Hotel was constructed in 1907 and decorated in the style of a Swiss chalet by Alfred Mildner, a German hotelier born in Alcase Lorraine, because the popular Oriental Hotel near the port was overcrowded each time passenger ships arrived. It catered to visiting dignitaries and tourists as well as wealthy Japanese and foreign residents. The hotel received its name from it location, tor, a Cornish word for ‘rocky hill’. Soon people started to call the road leading to it ‘Tor Road’. The hotel was located on the northern end of Tor Road, near the present-day location of the Kobe Club.

The Tor Hotel burned down in 1950, and little now remains of the earlier history of the site except for the giant Himalayan cedars in the front car park, thought to have been planted around 1890 by Arthur Greppi, a European businessman who had lived on the site before the hotel opened in 1908. There is also one small, red torii gate – all that remains of an Inari shrine that was located in the hotel garden and had several torii leading to it.

Lebanon

- St. Georges of Beirut was the place where Mr. Philby held court in the bar for seven years until he suddenly disapeared before reappearing in Moscow. The hotel or what is left of it, was built on one of the most valuable pieces of sea side property in central Beirut in the 1930s and became a gathering place for diplomats, reporters and spies. Yes, for once this cliche can be applied. In the sixties and early seventies, in Beirut's golden years, presidents, Hollywood stars and the rich Golf arabs, stayed at he hotel while visiting The Casino du Leban in Jounieh, Pepe Abed fish restaurant in Byblos or the Roman ruins in Baalbek. Lebanese-Palestinian writer Said K. Aburish has devoted a 200 page book to "The St. Georges Hotel Bar", published by Bloomsbury, London 1989. The destruction of the hotel in the so-called war of the hotels in December 1975 is vividly described by the American correspondent Jonathan Randal in his book "Going All the Way: Christian Warlords, Israeli Adventures and the War in Lebanon (Viking 1983). Randal was held hostage in the building during the fighting.

- The slim hope of the owner to rebuild the hotel was finally shattered by the powerful road bomb that killed prime ministe Rafik Hariri in February 2005. The neighbouring high rice Holiday Inn was also destroyed in 1975 and is, together with the St. Georges ruin, standing as an emty monument over the civil war.

- The beautiful Phoenicia Hotel re-opened as The Intercontinental some years ago but was also forced to close for a while in 2005 due to the Hariri bomb.

Malaysia

- Kuala Lumpur: Railway Station Hotel

- Penang: Runnymede Hotel

- Penang Hill: The Crag

Mozambique

- Beira: The Grande Hotel Beira was a luxury hotel in Beira, Mozambique that was open from 1952 to 1963. It continued to be used during the 1960s as a conference center and swimming pool. During the Mozambican Civil War (1977-1992) it became a refugee camp. The hotel opened in 1954, when it was billed as the "pride of Africa," and was widely regarded as the largest and most exquisite hotel on the continent. Its owners intended to include a casino, but failed to secure the necessary government authorization. The hotel was never profitable, and never attracted the wealthy clientèle it was intended to. It closed as a hotel in the early 1960s. The swimming pool and conference rooms continued to be used during the 1960s and even after the independence in 1975. The last event held in the hotel was the new year's eve party in 1980-81.

After independence in 1975 its basement was used as cells to hold political prisoners. Some members of the police and army started using the third floor as their living quarters. After 1981, it was taken over by the general population. The new guests used the entire parquet floors as fuel. The building has no running water or electricity, and is currently inhabited by more than 1,000 people.

Journalist Florian Plavec describes a visit to the hotel in a July 2006 feature in the Austrian newspaper Kurier. According to his accounts, virtually everything of any value has been looted from the hotel, including its marble and bathroom tiles, wooden flooring, sinks, and bathtubs. The former pool now serves as a water collector for clothes washing, and the former pool bar as a urinal. The hotel has also experienced structural damage, as trees continue to grow out of terraces, and floors collapsed.

The hotel in its actual state of decay has been shot by South-African photographer Guy Tillim in his serie "Avenue Patrice Lumumba"in 2007 (published by Prestel Verlag).

- Xai-Xai: Chongoene Hotel: Ruins remain the only victim of a bygone era of the Chongoene Hotel. Recently the South African company East Coast Development Corporation has shown interest in rehabilitating the hotel.

Pakistan

- Peshwar: Deans Hotel

Sri Lanka

Colombo

- Hotel Bristol

Switzerland

- Montreux Grand Hotel National, opened in 1875 as the first grand hotel in the resort on the Swiss Riviera that would eventually become known for its stately accommodation. The lights went out in the 1980s, when the hotel owners decided to close it down.

USA

Florida

- St. James Hotel in Jacksonville — after the Great Fire of 1901

Los Angeles

- The Ambassador Hotel, Hollywood, built 1921, demolished 2006.

California, Salton Sea

- Palms Motel

Unsurprisingly repulsed by the smell of rotting fish that besieged the town following a series of ecological disasters (the huge lake became so polluted that all marine life was doomed to end up dead on the sand banks), residents and visitors abandoned Salton City, California in the late 1980s. The Palms Motel remains though — at least its structure.

Detroit

- Lee Plaza Hotel

Abandoned in the 1990s, the 15-storey Lee Plaza Hotel is a monument to early 20th-century design, added to the United States National Register of Historic Places in 1981.

Liberty, N.Y.

- Grossinger's Resort - closed in 1986, remains destroyed by a fire in 2022.

New York

Many hotel buildings have been lost such as the

- Astor House on Broadway between Vesey and Barclay was designed by Isaiah Rogers and opened in 1836 and was demolished in 1913.

- Fifth Avenue Hotel on 23rd to 24th Streets that was designed by William Washburn and had the first hotel elevator and opened in 1858 and was demolished in 1908.

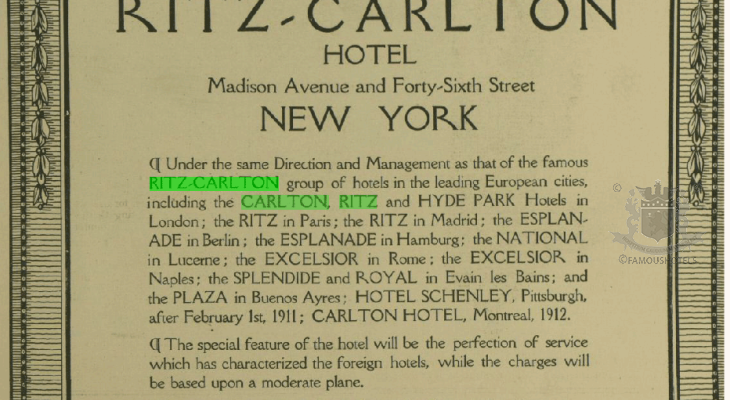

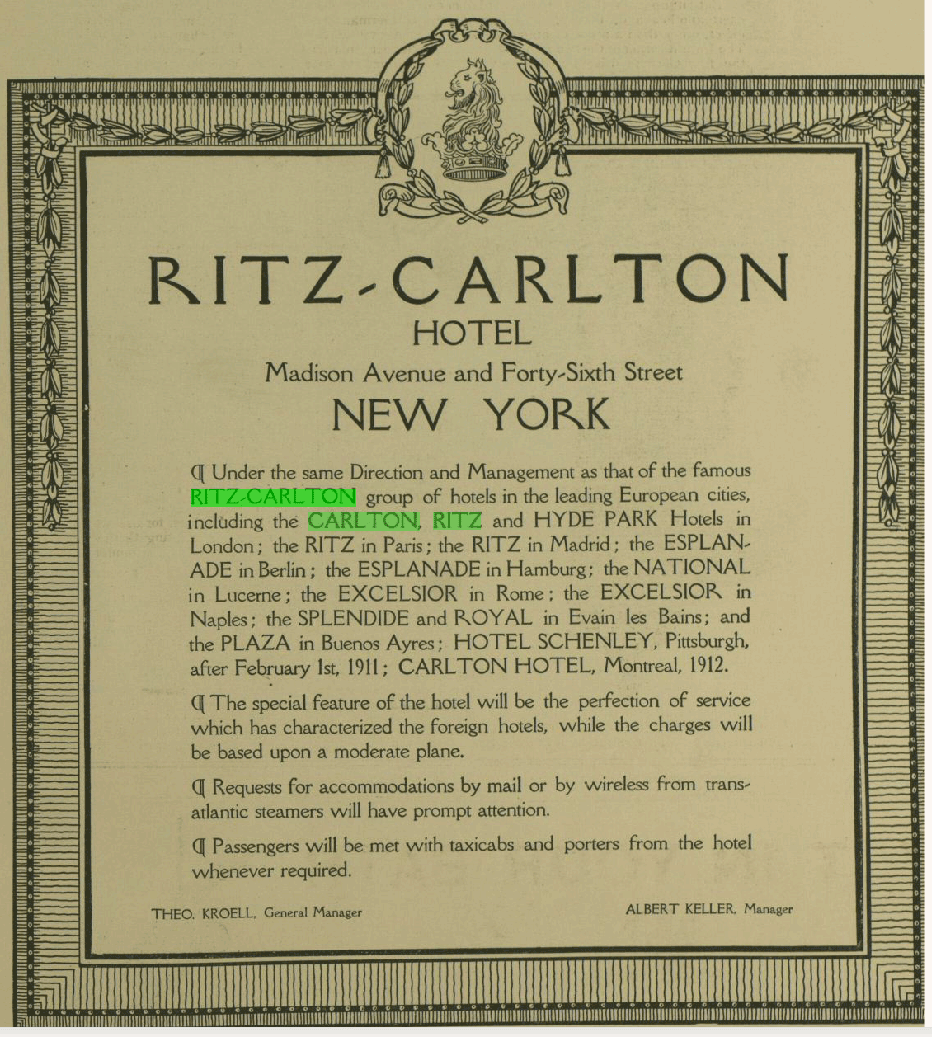

- The Ritz-Carlton, designed by Warren & Wetmore, architects of the new Grand Central Terminal. The Ritz-Carlton, on Madison Avenue and 46th Street, opened at the end of 1910, reached its fashionable heyday at about the time of the First World War. Its ballrooms and lobbies, and some say its service and general ambiance, where between than those furnished later elsewhere at the Ritz Tower. The Ritz-Carlton was razed in 1951 to provide a site for an office building.

- McAlpin (1912), now a condominnium building

- Drake Hotel (1927), demolished 2007.

Notable guests of the old 640-room hotel included Frank Sinatra, Muhammad Ali, Judy Garland, Jimi Hendrix and Glenn Gould. In the 1960s and 70s, rock groups like The Who and Led Zeppelin chose to stay at the Drake when they visited The Big Apple from the UK. Famously, Led Zeppelin reportedly had $203,000 in cash stolen from a safe deposit box at the hotel. famoushotels.org columnist Stan Turkel ran the Drake for several years in the Sixties. The famous nbightclub was called Shepheard's, which was Manhattan's first discotheque, named after the famous Cairo hotel. It was Egyptian-themed with two large gold sphinxes either side of its entrance. The Drake Room was one of the places to eat and be seen in Manhattan. The executive chef, a man called Nino Schiavone, championed the idea to have waiters prepare food at the tableside. Cuts of prime steak mixed with sweet butter, fresh chives and other seasonings were flamed with cognac and sherry at the tables of an eclectic and well-heeled crowd. Providing the ambience at The Drake Room was a famous salon piano player, Cy Walter. So renowned was the pairing of pianist Walter at The Drake Room, Turkel arranged for MGM Records to record an album. Released in 1966, the cover of the record, Cy Walter at The Drake, was a photograph of Walter with his Steinway grand piano outside the Drake entrance, on 56th St. - Traymore Hotel (1879), Atlantic City, N.J.; demolished

- Vemon Manor Hotel (1924), Cincinnari, OH.; convened to ahospital building.

- Savoy Plaza Hotel is now the site of what was the GM building. For a time, it was the Savoy Hilton Hotel.

- Ambassador Hotel on Park Avenue, which was Sheraton Ambassador for a time.

- Hotel Theresa opened in 1913 on 125th Street and Seventh Avenue in Harlem. It became famous for accepting both races in the 1940s. It closed its doors as a hotel in 1970. In 1971, the hotel was converted to an office building with the name Theresa Towers and was declared a landmark in 1993 by New York’s Landmark Preservation Commission.

- GROSSINGER’S CATSKILL RESORT AND HOTEL In its heydays Grossinger’s Catskill Resort Hotel was attracting more than 150,000 guests per year to its 35 buildings, a golf course, beauty salon, pool, and even artificial ski slope. The 1972 death of its legendary hostess, Jennie Grossinger, though, coincided with the death of the hotel’s heyday as the rich and famous sought glamour elsewhere. Abandoned in 1986, the Catskills resort provided the location one year later for Dirty Dancing.

Kauai, Hawaii

- COCO PALMS RESORT Once a star-studded luxury resort on the Hawaiian island of Kauai, Coco Palms was so badly damaged by hurricane Iniki that it was forced to close in 1992. Left abandoned since then, the hotel that once hosted the Elvis Presley movie Blue Hawaii was further gutted by fire in 2014; it remains unclear whether the blaze was started by the ghost of the King ... but we think it probably was.

Philadelphia

- DIVINE LORRAINE HOTEL Standing at the corner of Broad Street and Fairmont Avenue in North Philadelphia, The Divine Lorraine Hotel is an abandoned hotel with a future. Derelict since 1999, the hotel has attracted ruin aficionados, graffiti artists, and vandals to its 11-storey playground — but plans are well underway to restore the iconic building to its former glory. Once home to a cult, the Divine Lorraine is also significant as the first racially integrated hotel in America. Following a $US44 million ($57 million) renovation, the blighted building could open as early as the end of 2016, which would make it the first (and only) former creepy abandoned hotel on our list.

Pocono Mountains

- BUCK HILL INN closed in 1990. At this time — when owner Jacob Keuler’s wife fell ill — Keuler drove her to the hospital, checked her into the psychiatric ward, went back to the hotel, and shut the whole place down, leaving everything as it was.

Kansas City

- Muehlebach: The original 12-story building was constructed in 1915. It was designed by Holabird & Rocheand, 144 feet (44m) high and owned by George E. Muehlebach, whose father, George E. Muehlebach Sr., founded the Muehlebach Beer Company. The younger Muehlebach also built Muehlebach Field, which achieved its greatest prominence under the ownership of Barney Allis. In 1952 a 17-story western annex and parking lot were added. The entire hotel underwent a major restoration in 1976 and operated for a time as the flagship of the Radisson hotel chain under the name Radisson Muehlebach Hotel before finally closing in the 1980s.

Charleston

- West Virginia, Daniel Boone Hotel, opened in 1929, closed 1981

Chicago

- The Edgewater Beach Hotel was a hotel in the far-north neighborhood community of Edgewater in Chicago, Illinois. Designed by Benjamin H. Marshall and built in 1916 for its owners John Tobin Connery and James Patrick Connery, it was located between Sheridan Road and Lake Michigan at Berwyn Avenue. An adjacent tower building was added in 1924. The hotel closed in 1967, and was soon after demolished.

The Edgewater Beach Apartments were completed as part of the hotel resort complex in 1928. The "sunset pink" apartments, complimented the "sunrise yellow" hotel in a similar architectural style. The apartments remain standing and have been listed on the National Register of Historic Places. More history --> Wikipedia - The Raymond Hotel dominates the South Pasadena landscape. It opened in 1886. The Raymond remained Southern California's leading resort hotel until Easter Sunday, 1895. On that day, an ember flew from one of the Raymond's 80 chimneys landed on the hotel's wood-shingle roof. No lives were lost, but within a couple hours the Raymond was no more. In 1901 Walter Raymond was able to rebuild and reopen his hotel. With 400 rooms, golf links, and formal gardens, the Raymond's second iteration was even grander than the first. At the entrance, a new floral display, augmented by 575 electric lights, announced in ten brightly colored letters that visitors had arrived at "THE RAYMOND." Guests then entered a tunnel -- which still exists today, though sealed, under Raymond Hill -- and ascended into the hotel via elevator. In the 1930s, facing intense competition from Pasadena's newest luxury resort, the Huntington Hotel, the Raymond was unable to remain profitable. A bank foreclosed on the aging property in 1931 and, in 1934, the Raymond was demolished.

This list is growing — with the help of our corresponding friends. Please send us names and photographs of lost hotels.

Thank you

- bristol

- budapest

- cairo

- china

- continental

- egypt

- excelsior

- frank sinatra

- germany

- grand hotel

- hilton

- hong kong

- hotel metropole

- hungary

- imperial

- india

- jacksonville

- lost hotels

- metropole

- muhammad ali

- national

- new york

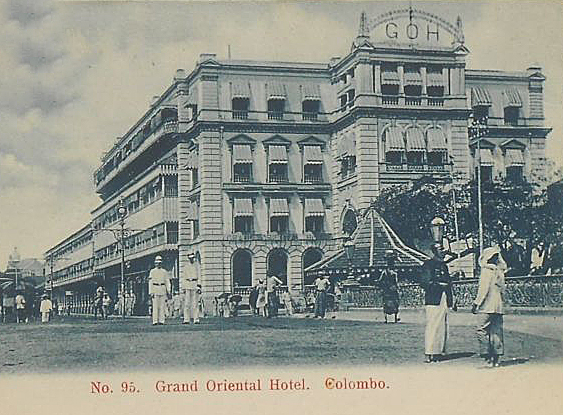

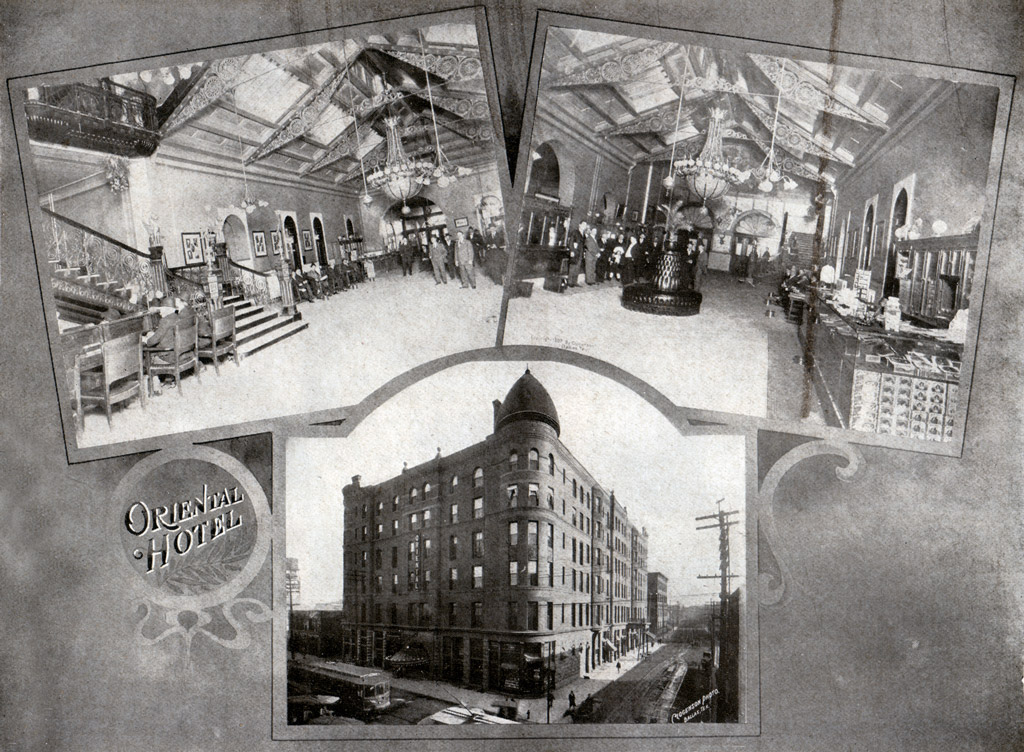

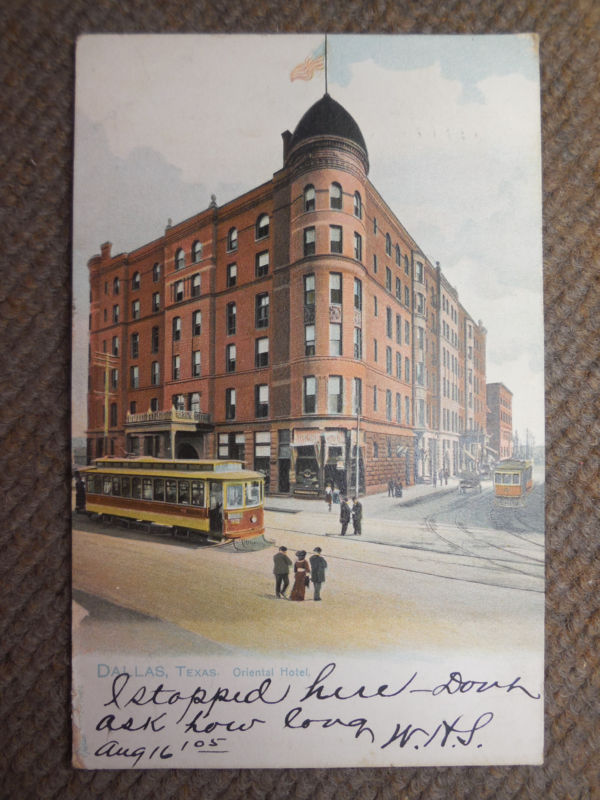

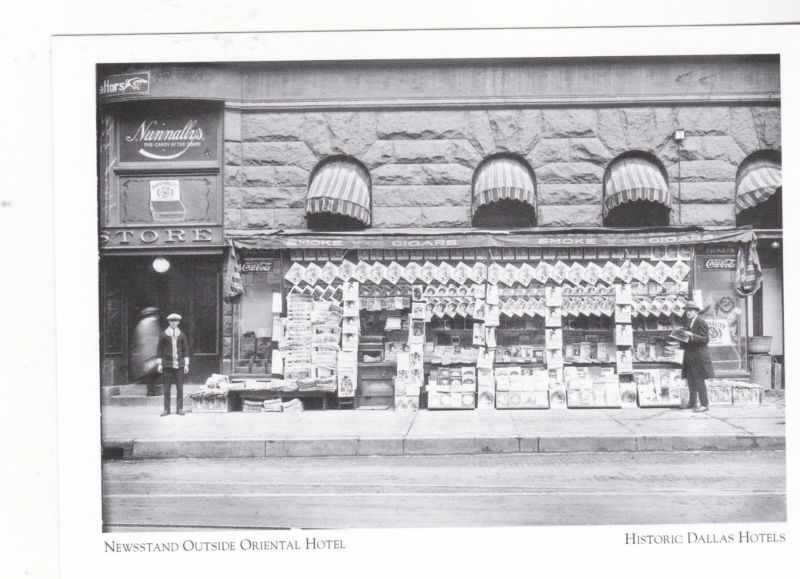

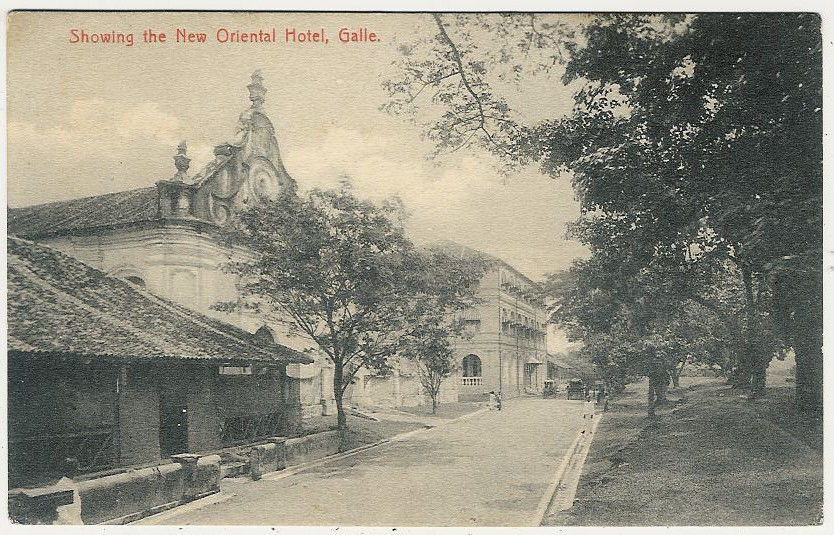

- oriental

- oriental hotel

- penang

- pera palace

- prince of wales

- queen victoria

- russia

- savoy

- schlosshotel

- semmering

- shepherd

- shepherds

- sinatra

- stan turkel

- sting

- südbahnhotel

- thomas cook

- thomas mann

- uk

- usa

- vienna

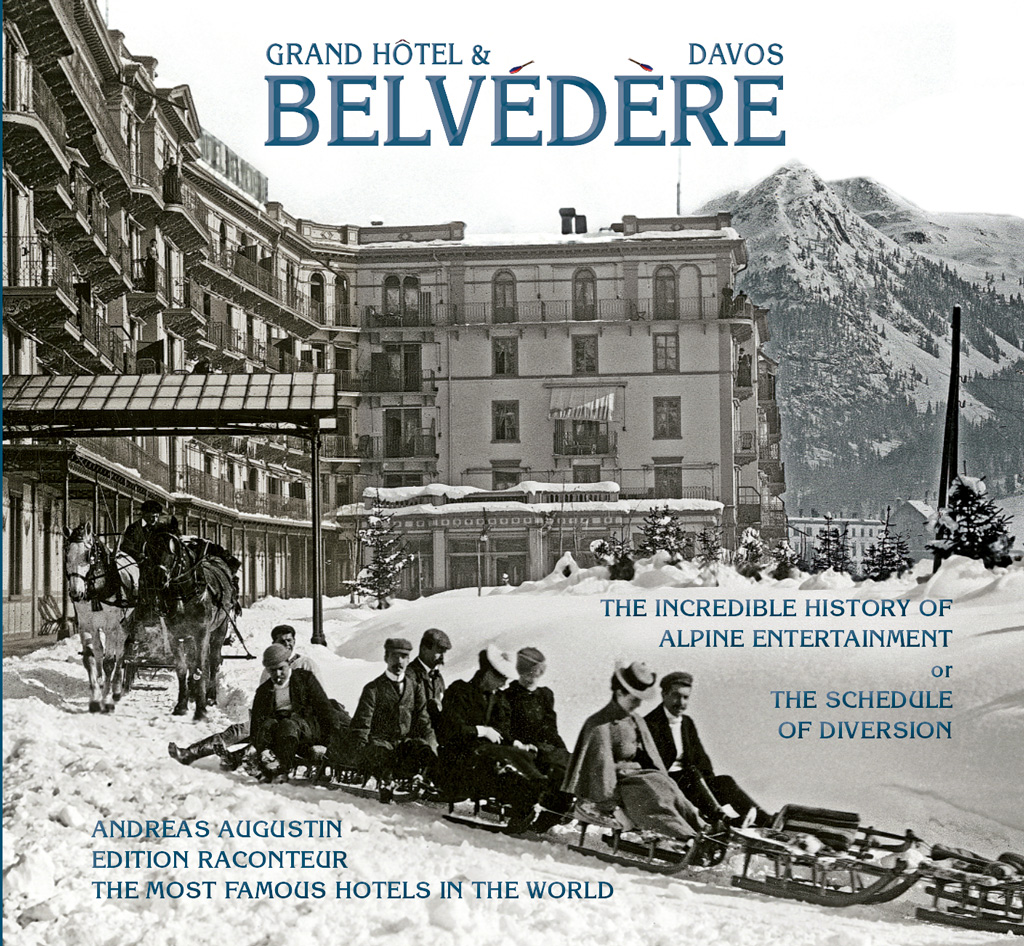

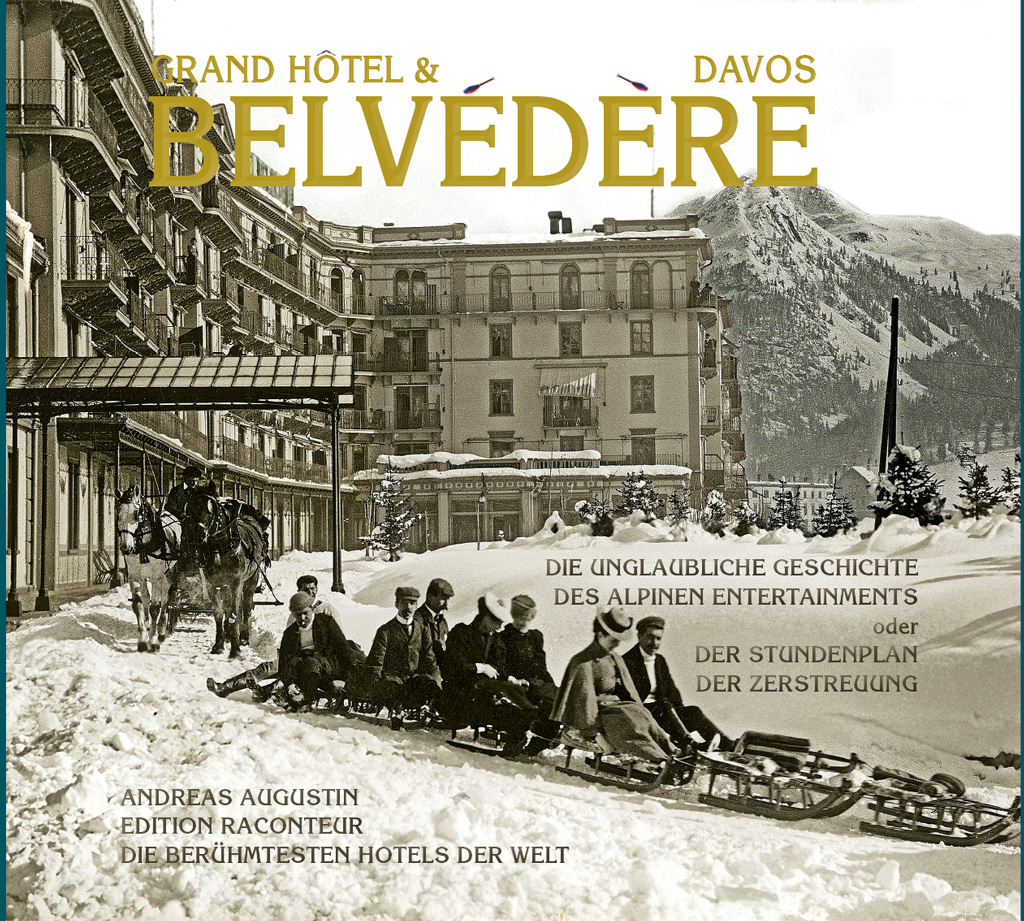

A Winter Arrival at the Grand Hotel BELVÉDÈRE

( words)

A Winter Arrival at the Grand Hotel Belvedere

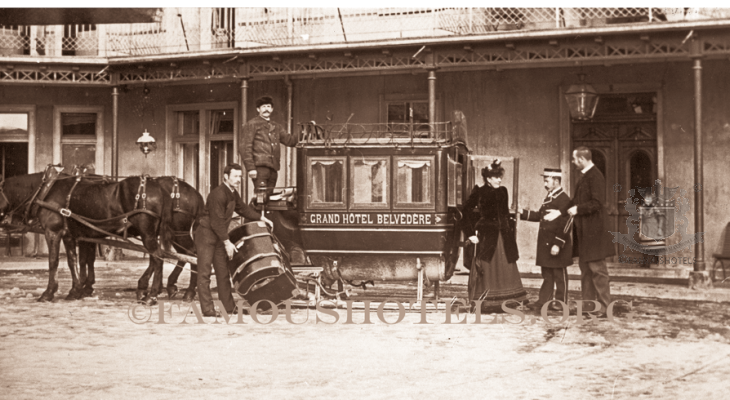

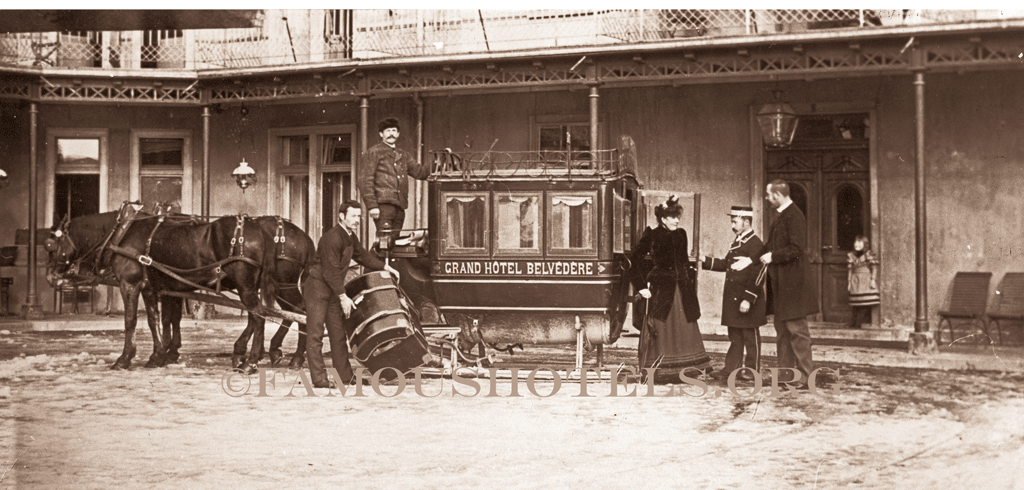

In a winter around 1900, a horse-drawn carriage on runners glided to a halt before the Grand Hotel Belvedere in Davos, Switzerland. The snow-covered landscape framed an elegant arrival: two uniformed hotel staff swiftly unloaded luggage from the carriageâ's roof, their breath almost visible in the crisp alpine air. A distinguished lady, dressed in a flowing black gown, stepped carefully onto the packed snow. At the entrance, a senior hotel official, impeccably dressed, extended a warm welcome.

This remarkable moment was captured by A.L. Henderson, court photographer to Queen Victoria. His lens preserved not just a scene, but an era—the golden age of grand hotels, where winter retreats in the Swiss Alps were a mark of sophistication and health. The Belvedere, already a renowned sanatorium and luxury retreat, stood as a beacon of hospitality, offering warmth, refinement, and impeccable service to Europe's elite.

Henderson's photograph remains a treasure of both photography and hospitality history, a glimpse into a world where the arrival at a grand hotel was as much a spectacle as the stay itself.

---------

Alexander Lamont Henderson (1838*/“1907) was a Scottish-born photographer renowned for his contributions to Victorian-era photography. His work included portrait photography, as evidenced by cartes-de-visite and cabinet cards from the 1860s to the 1880s.

In 1884, Queen Victoria awarded Henderson a Royal Warrant, recognizing his skill in capturing everyday royal life. This honor allowed him to document various aspects of the royal household, contributing significantly to the visual history of the British monarchy. After Queen Victoria's death in 1901, Henderson retired from professional photography. He then embarked on photographic tours across Europe, visiting countries such as France, Italy, and Spain, further enriching his portfolio with diverse cultural scenes. Henderson passed away in 1907, leaving behind a legacy that offers a valuable glimpse into 19th-century British society and the royal family.

The Fall of a Jewel: The Attack on Hotel Bristol, Odessa, Ukraine

( words)

The Fall of a Jewel: The Attack on Hotel Bristol, Odessa

The Fall of a Jewel: The Attack on Hotel Bristol, Odessa

Odessa, often called the Nice of Ukraine, mirrors the charm of the Côte d'Azur with its Black Sea coastline, elegant boulevards, and vibrant cultural life. Its sun-drenched beaches and historic architecture make it a timeless seaside retreat. On the night of January 31, 2024, the heart of Odessa trembled. Russian missiles rained down upon the historic center, shattering not only buildings but the spirit of a city steeped in history. Among the wounded was a symbol of Odessa’s grandeur—the illustrious Hotel Bristol.

Since its grand opening in 1898, the Bristol stood as a beacon of elegance. Designed by renowned architects Alexander Bernardazzi and Adolf Minkus, its façade, a masterpiece of Renaissance revival, spoke of an era when Odessa was the gateway between East and West. It welcomed dignitaries, artists, and travelers, its marble halls echoing with conversations of empire, revolution, and rebirth.

Through wars, political upheavals, and the shadow of the Soviet era—when it was renamed *Hotel Krasnaya*—the Bristol endured. After the fall of the USSR, it faced years of neglect, but like the city itself, it rose from decay. Painstakingly restored, the hotel reopened in 2010, reclaiming its place as a crown jewel on Odessa’s skyline.

But history, it seems, repeats its tragedies. As missiles tore through the night sky, the Bristol’s storied walls crumbled. The same halls that once hosted grand balls and whispered secrets of a bygone age now stood in ruins, a silent witness to the brutal assault on Ukraine’s cultural soul.

But history, it seems, repeats its tragedies. As missiles tore through the night sky, the Bristol’s storied walls crumbled. The same halls that once hosted grand balls and whispered secrets of a bygone age now stood in ruins, a silent witness to the brutal assault on Ukraine’s cultural soul.

The Bristol’s fall is more than the destruction of a building—it is an attack on memory, on heritage, on the very essence of Odessa. Yet, as history has shown, this city and its treasures have a resilience no bomb can erase.

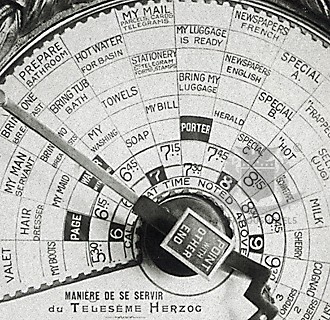

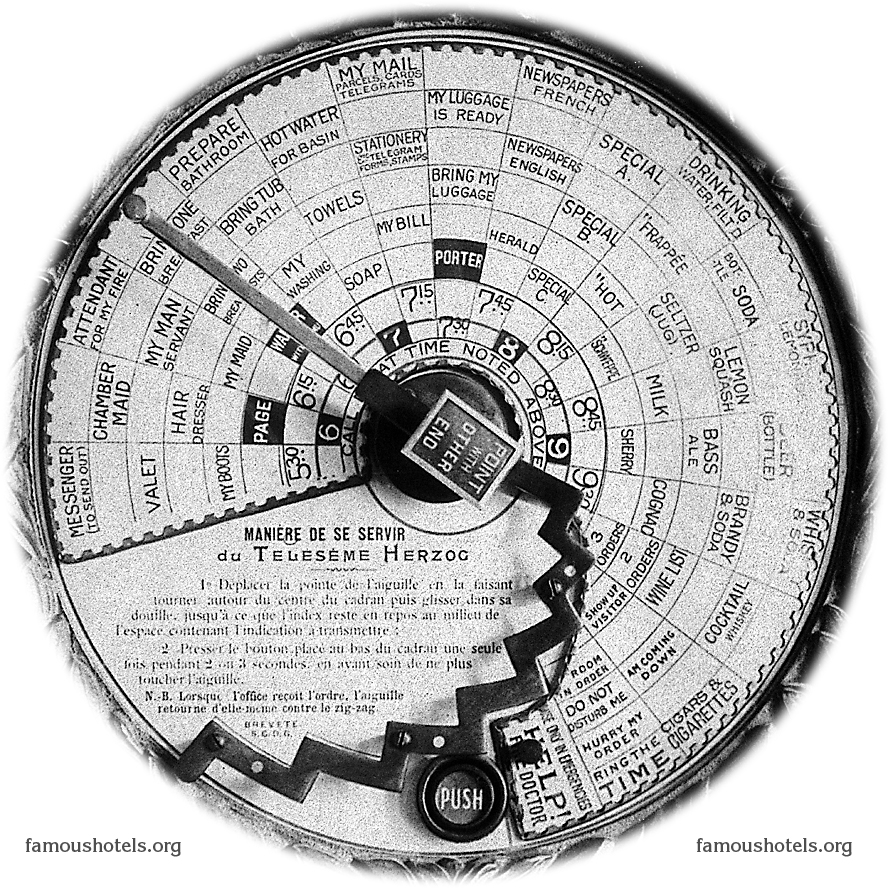

Teleseme: 104 good reasons to call the staff

( words)

By Andreas Augustin / famoushotels.org

International hotels around 1900 were filled with inventions lavishly described in their promotional literature. Guests were assured that the air they breathed was the freshest possible, thanks to novel ventilation systems. Doors closed quietly on nonslamming hinges. To open them, you didn't have to leave your bed. Services like shoe-polishing were provided unobtrusively via the 'servidor, a compartment in the room door accessible by small doors on either side (still in use at The Oriental in Bangok and at The Peninsula Hong Kong, for example). Once central clock was in charge of the clocks in all rooms. And so on.

Here we have a sophisticated machine for you: the Herzog Teleseme.

In 1894, *The Electrician* reported that a New York hotel had replaced its new telephone service with a teleseme system. The hotel cited guest complaints, especially from women using phones to lodge grievances, and operators overwhelmed by calls. The teleseme, invented in the 1880s by F. Benedict Herzog and Schuyler Wheeler, became an emblem of hotel luxury before the widespread adoption of telephones in guest rooms.

The teleseme allowed guests to make specific service requests through a dial mechanism offering over 100 options. Requests, ranging from food and beverages to specific staff like valets or chambermaids, were sent to an office where attendants processed orders. This streamlined process avoided delays caused by buzzing the front desk and waiting for a staff visit. For example, guests could order anything from lemon squash to oysters or newspapers to laundry service.

Herzog, an American electrical engineer and inventor, founded the Herzog Teleseme Company in New York, which manufactured the devices. The company marketed telesemes as modern, efficient, and capable of integrating into existing hotel wiring. Patented in 1895, they were installed in prestigious hotels like the Élysée Palace in Paris, the Jefferson Hotel in Richmond, and Statler Hotels. The teleseme’s dial even included options like “call me at a specific time but do not disturb until then,” highlighting its innovation.

Despite its popularity, the teleseme had limitations. It could not handle complex requests, sometimes leading to errors. For instance, one guest requesting water was receiving champagne instead. By the 1910s, hotels transitioned to PBX systems, which provided telephones in every room, rendering telesemes obsolete. Some hotels resisted the change initially, but the technological shift eventually prevailed.

Herzog later adapted the teleseme’s principles for police signaling in New York, but the original device disappeared from use. Today, the teleseme remains a fascinating relic of hospitality history, though finding an intact example for museum purposes has proven elusive.

Here one could press for example for

My fire, prepare my bathroom, my mail post cards telegrams, newspapers in French, my luggage is ready or bring my luggage, porter, Herald, frappée, bottle of soda water, drinking water, Sherry, Cognac, Brandy and soda, cigars and cigarettes, I am coming down or show up visitor, hurry my order or do not disturb me. The first (or last) button was dedicated to the simple outcry HELP, fire, doctor!

The Teleseme was invented to send instructions to the staff from a guest's room, long before telephones became a standard in every room. Its list of services shows us the standards of a true luxury hotel around 1900. We have added a high resolution picture for our readers to print out.

The Teleseme was – as described in historic technical papers – a system of apparatus for electric signals to be transmissioned by moving an indicating finger or index of as many as 104 different buttons, each connected by a separate wire with the push button (at the bottom of the device).

A teleseme from Electric Telegraphy (1896) came with the following instructions:

GRASP the crank PIN, and move it IN or OUT, from centre, and RIGHT or LEFT, until it REMAINS AT REST on what you want AFTER you remove your hand then PRESS the red "push" button once firmly, and don't touch the pointer after that. OBSERVE: The pin remains where you set it, until your want is known. Then it moves back to the "rib."

Art in Hospitality

( words)

Top: Edward Hopper, Hotel Magazin

Curated by Andreas Augustin

To view all pictures in full beauty, please open them in a separate window (mouse right click)

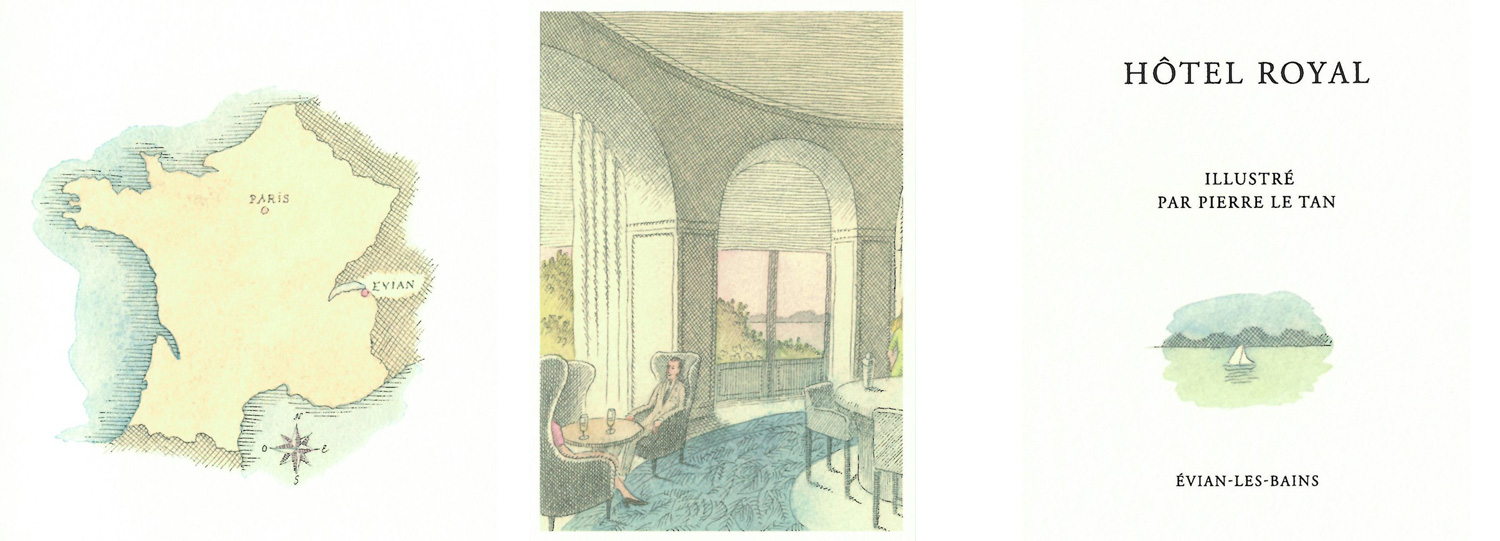

Pierre Le-Tan

Pierre Le-Tan (1950–2019) was a distinguished French illustrator and painter, celebrated for his unique ability to encapsulate the charm and ambiance of various settings, notably hotels. Born in Paris to a Vietnamese father and a French mother, Le-Tan's multicultural heritage deeply influenced his artistic perspective. His father, Lê Phổ, was a renowned painter, which immersed Pierre in a world of art from an early age.

Pierre Le-Tan (1950–2019) was a distinguished French illustrator and painter, celebrated for his unique ability to encapsulate the charm and ambiance of various settings, notably hotels. Born in Paris to a Vietnamese father and a French mother, Le-Tan's multicultural heritage deeply influenced his artistic perspective. His father, Lê Phổ, was a renowned painter, which immersed Pierre in a world of art from an early age.

Le-Tan's illustrations are characterized by delicate lines, subtle color palettes, and a nostalgic aura that transports viewers to serene environments. His work often graced the covers of esteemed publications like *The New Yorker*, *Vogue*, and *Harper’s Bazaar*, showcasing his versatility and appeal.

One of his notable projects includes illustrations for the Hôtel Royal Évian, where he masterfully depicted the hotel's grandeur and tranquil surroundings. These artworks not only highlight the architectural beauty of the establishment but also evoke the serene atmosphere experienced by its guests.

Le-Tan's legacy extends beyond his illustrations; he was also an avid collector, amassing a diverse array of art and antiques that reflect his eclectic taste and artistic vision. His personal collection was so remarkable that it was featured in a Sotheby's auction, underscoring his profound appreciation for art in various forms.

In essence, Pierre Le-Tan's work offers a unique lens through which we can appreciate the intricate relationship between art and hospitality. His illustrations serve as timeless representations of hotel spaces, capturing their essence and inviting viewers to experience the subtle beauty of these environments.

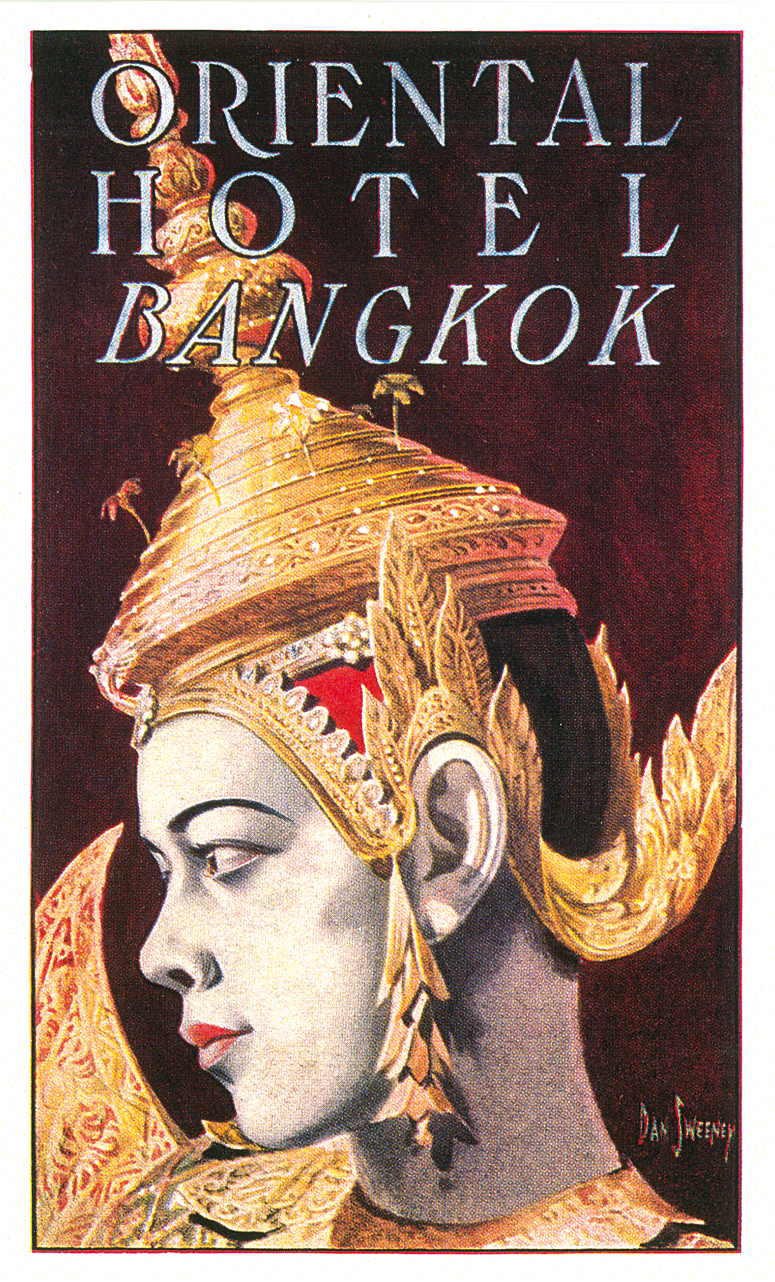

Dan Sweeney's Hotels

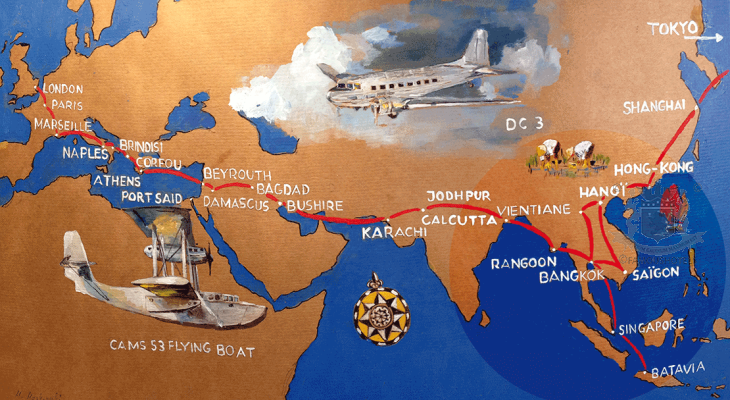

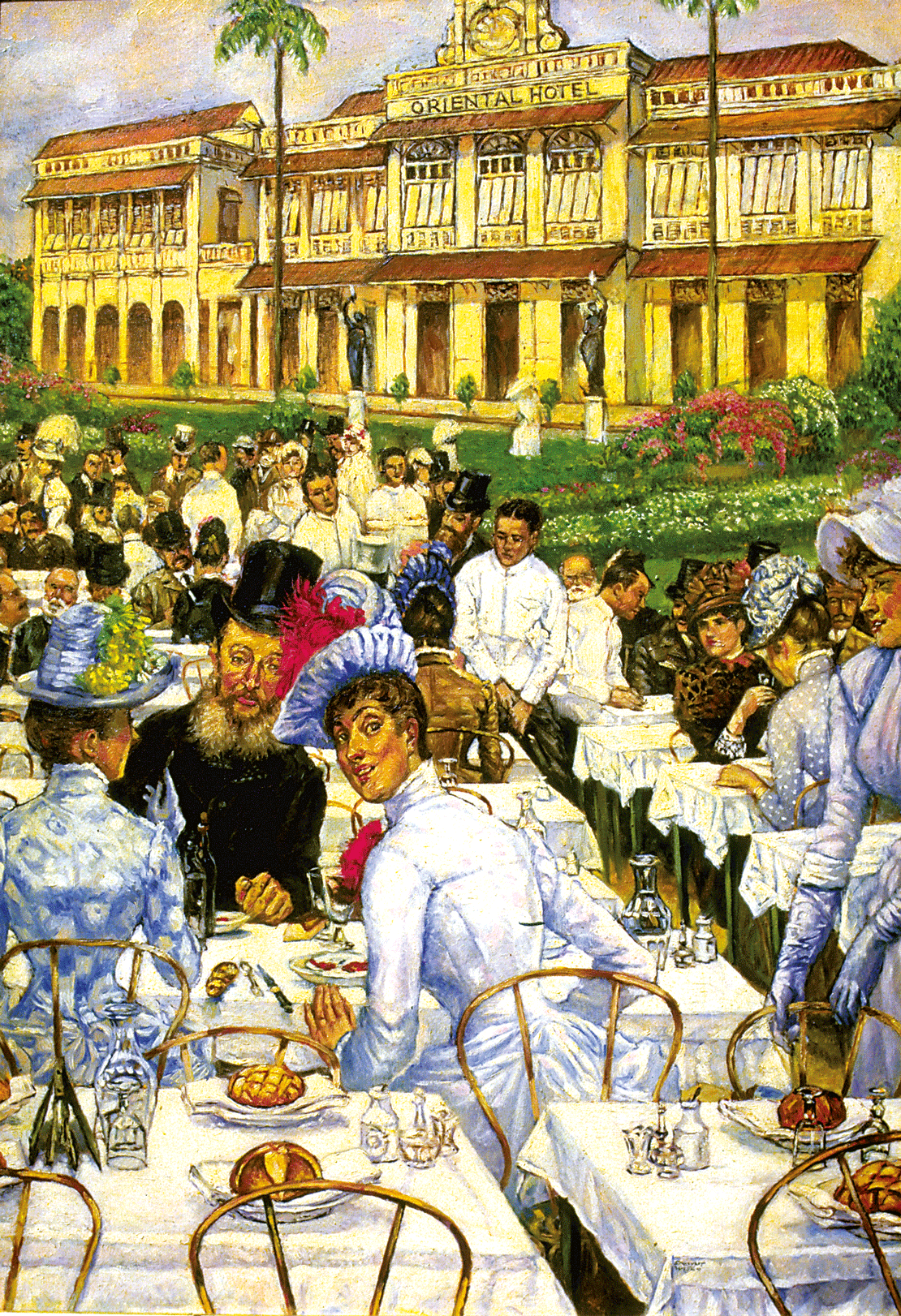

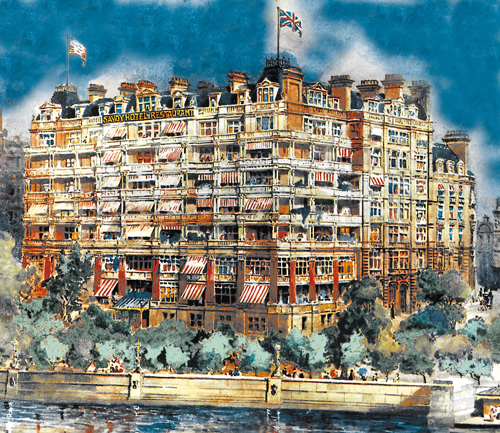

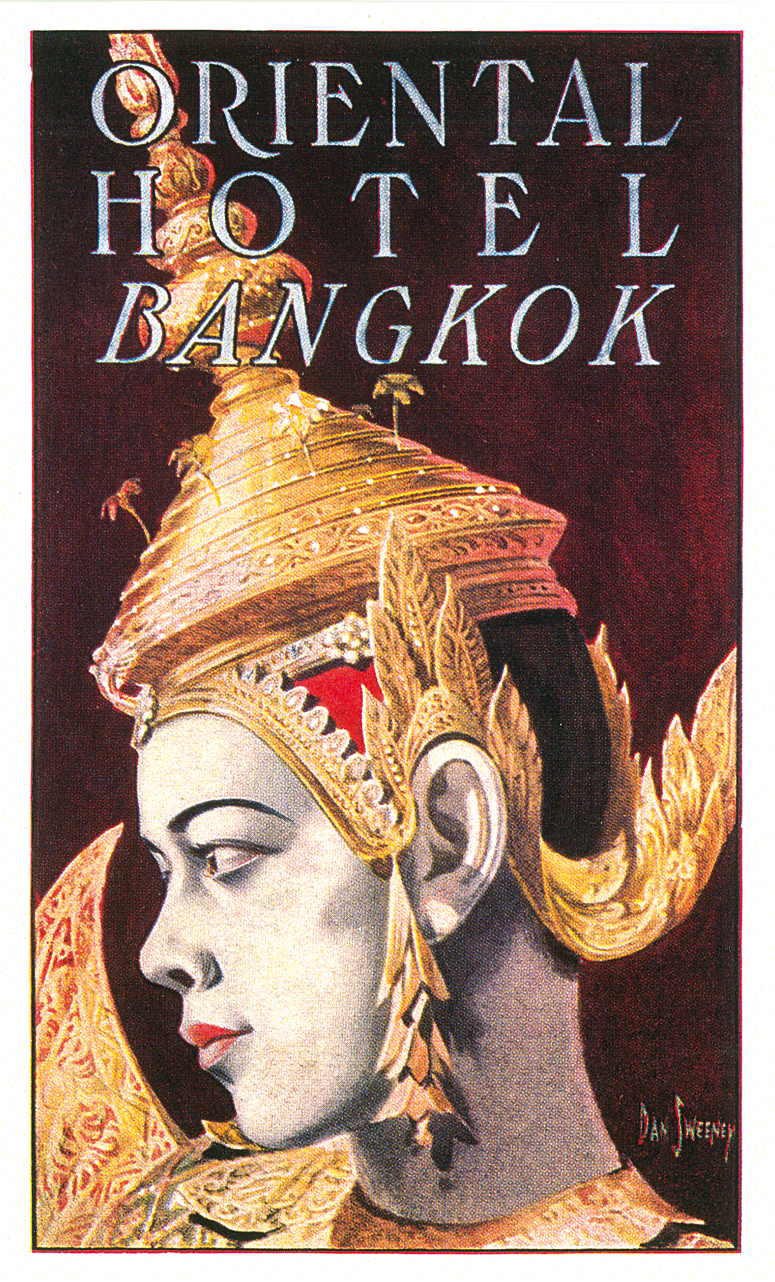

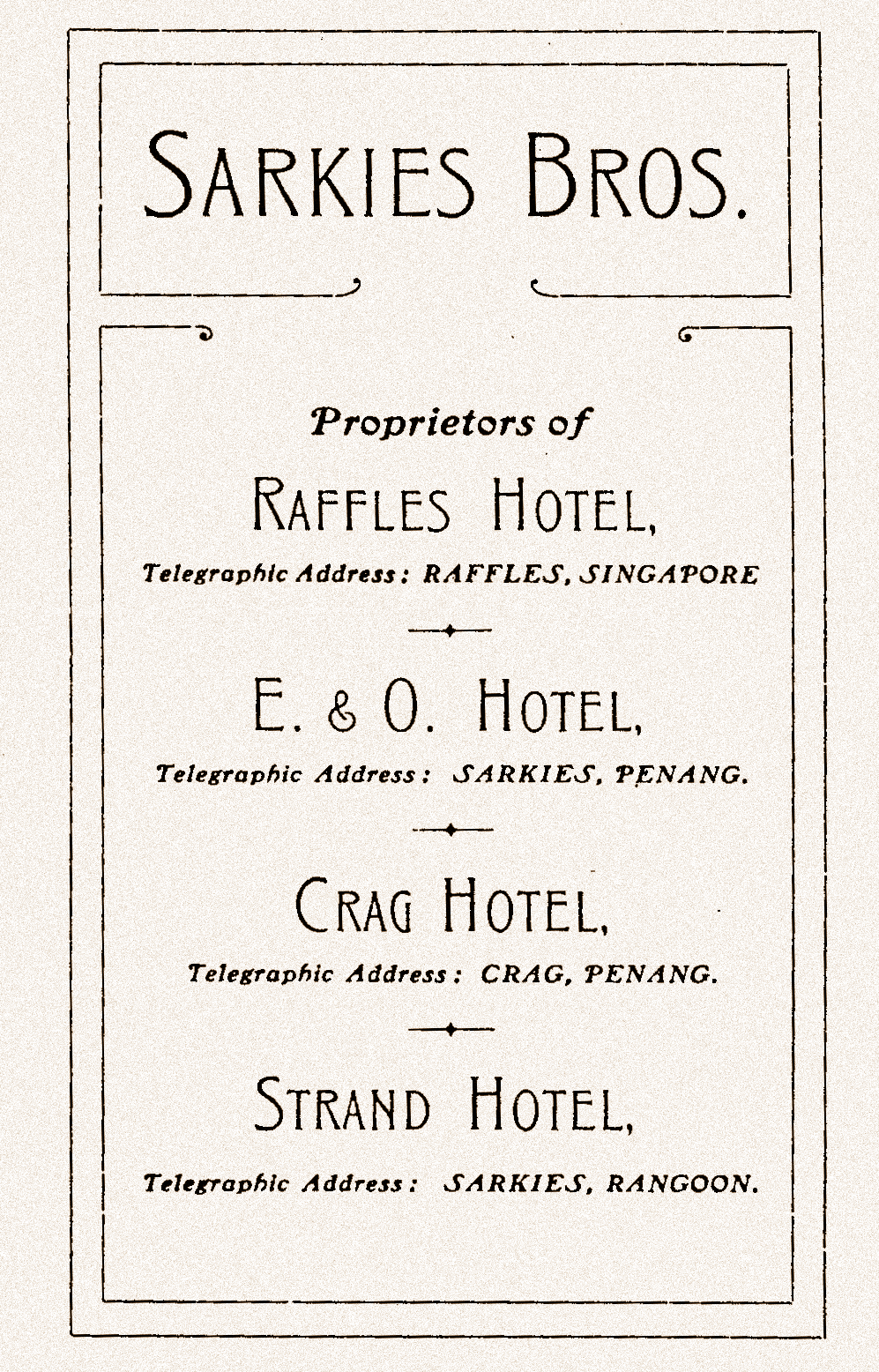

During the 1920s an American was the first to introduce the art of "hotel posters" to the leading hotels of Asia. He helped them to establish a corporate identity of a very special nature. His fine posters were used as labels or covers for hotel brochures.

His name was Daniel C. Sweeney (*1880, Sacramento, California, †1958). Sweeney was a seasoned illustrator with a track record going back to the San Francisco Chronicle and World Traveler Magazine. Sweeney also painted posters for theater lobbies, which led to doing travel posters. He began work for several steamship lines and traveled around the world, to many out-of-the-way places, doing background research for unusual poster subjects. One of his most successful series of pictures was of pirate subjects for the Grace Lines.

For many years, Sweeney was a steady contributor of fiction illustrations to Collier's magazine, particularly of sea and Western subjects rendered in wash or transparent water-colour.

For many years, Sweeney was a steady contributor of fiction illustrations to Collier's magazine, particularly of sea and Western subjects rendered in wash or transparent water-colour.

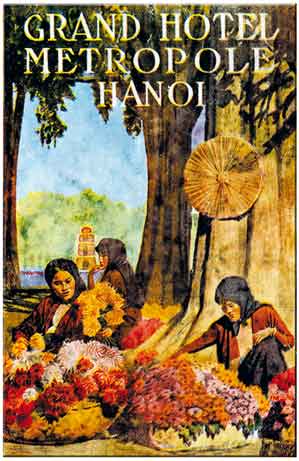

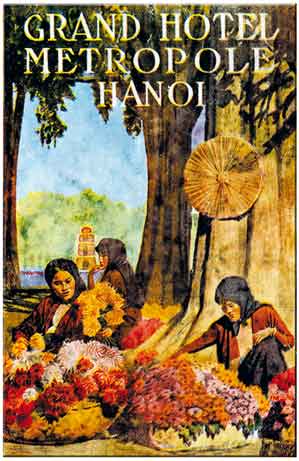

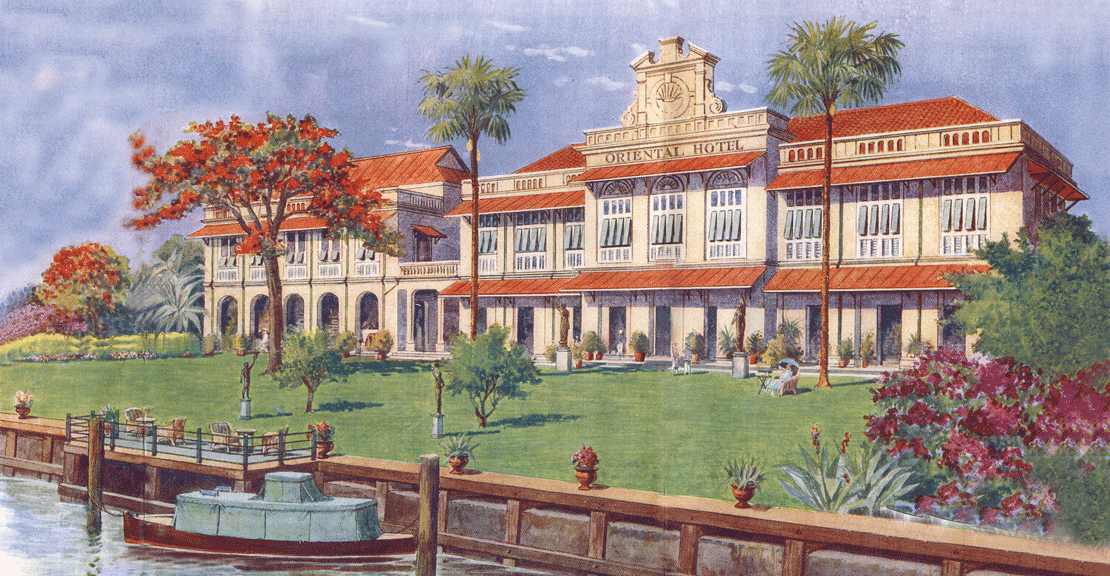

He was most likely discovered for Asia by The Oriental Hotel in Bangkok, where he created a poster depicting a Thai dancer. This poster soon graced the 1920s sales brochure of the hotel. Sweeney also drew posters for The Peninsula and the Hong-Kong Hotel as well as The Peak Hotel, Repulse Bay Hotel, all in Hong Kong; Grand Hotel des Wagons-Lits, Peking; Astor House, Shanghai; Majestic Hotel and Palace Hotel, both in Shanghai; the Continental Palace Hotel, Saigon; the Manila Hotel and the Metropole in Hanoi.