The Savoy

The Savoy has reopened on 10.10.2010 after an extensive renovation. The hotel is back to its great heritage, fully equipped with state-of-the-art technology and certainly fit for the next decades.

The two Tonys and Peter, the doormen, still greet you at the entrance. Inside you dine at 'Oscar', the resurrection of the River Restaurant, have high tea at the lobby or a drink at the bar.

In the summer of 1889 – the days of Gilbert and Sullivan, the heroes of English operetta – The Savoy opened its doors. It was the creation of theatre impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte. He engaged an aspiring young Swiss, César Ritz, to manage the hotel. Rith brought in Auguste Escoffier – a young chef who would rise to become the ‘Emperor of all chefs’.

Enrico Caruso sang at The Savoy, Sarah Bernhardt, Oscar Wilde and Dame Nellie Melba of Pêche Melba fame (created at The Savoy) – made it their London residence. Hollywood stars arrived. The American Bar became the watering hole of american prohibition refugees. Every Prime Minister chose The Savoy as a refuge of privacy (Sir Winston Churchill founded ‘The Other Club’ at The Savoy, which still meets here). From Chaplin to Pavarotti, from James Bond to Harry Potter – this is the place to be seen, to party, or to hide.

How the Stage was Set

HISTORY IN BRIEF 1889: Opening year. 2005: Fairmont bought the hotel

HISTORY IN DETAIL

1889: a new company was registered on 28 May, its purpose being to 'acquire the large building, called The Savoy Hotel', and a prospectus issued to potential investors. It had a share capital of £200,000, split evenly between £10 ordinary and £10 preference shares, and a further £140,000-worth of debentures.

1889, 27 July (a Saturday): The Savoy opens. 250 apartments, 60 private sitting rooms, 67 bathrooms. Shaded electric lights everywhere, no gas used! No charge for baths, lights or attendance! Large asscending rooms (lifts) running all night (making the usual hard to sell top floor rooms equal in in every respect to the lowest).

1889, December-1898, March: Cesar Ritz is general manager of the hotel, chef de cuisine is Auguste Escoffier Ritz did everything he could to abolish old fashioned attitudes. With the support of the press and even members of parliament, he introduced Sunday evening dinners and made it fashionable to attend them. The sudden demand for fresh bread on Sundays (no London baker would provide fresh bread on the day of the Lord) led to the employment of a baker from Vienna, a tradition that has been upheld for over a hundred years. This baker brought with him the delights of Viennoiserie, from crisp dark rye bread to rolls and croissants, and the mouth-watering delights of Austrian cakes, strudels and pastries.

1893: Oscar Wilde stayed at the hotel (see 'famous guests').

1894: The Grand Hotel Rome opened as part of the hotel group, (third hotel in the group: Claridge's, London)

1910: The Embankment façade was extended outwards to increase the size of the river-front suites and to provide space for new bathrooms. It was given a new front and crowned with an extra storey. It was time to say farewell to the pillared balconies that were such a feature of the original design. The 1910 renovations also brought 100 new telephone ‘instruments’, new radiators and the total number of bathrooms to 244.

1923: The Savoy had ‘500 Bedrooms and Bathrooms’ and was described in Muirhead’s London as ‘a very large hotel overlooking the Thames, with a cosmopolitan clientèle, a fashionable restaurant and glass-covered terrace.’ Prices for a single and double started from 15s 6d and 25s a night, respectively with an en suite bathroom from 30s and 42s, while suites began at 63s. In contrast, the price of meals was proportionately much higher than today. Breakfast was available at 3s 6d, the set lunch was 8s 6d, dinner 12s 6d. The weekly dinner and dance was 15s 6d.

1945: No dinner was welcomed with greater emotion than the restaurant’s victory-night celebration. Requests for tables from optimistic regulars had arrived as early as 1941. Chicken – easily available – was the main course.

1990: On 12 February, a fire razed the Savoy Theatre to the ground.

1999: The Savoy received the prestigious “Investors in People” award, a national quality standard which sets a level of good practice for improving an organization’s performance through its employees. This is a most significant award, as it looks behind the scenes and tells everything about the management’s attitudes to human resource management issues.

2005: The Savoy was bought by the international hotel group Fairmont.

2016: The Savoy, a copy of the book by Andreas Augustin and Andrew Williamson, fetched US$2.800,-- at an auction in New York.

Marilyn Monroe held a press conference at The Savoy. In the beginning we meet Helen Porter Mitchell alias Nellie Melba – named after her hometown Melbourne. She had pêche Melba on good days and Toast Melba when she was on a diet. The thin slices of toast were actually invented for Marie Ritz, but the wife of the manager relinquished the honour of having a toasted slice of bread named after her and left the pleasure to Madame Melba.

In 1893 Oscar Wilde stays at the hotel. His homosexual affair with Lord Alfred ‘Bosie’ Douglas brought his flamboyant lifestyle at The Savoy to a bitter end. He had taken adjoining rooms on the third floor for himself and Lord Douglas. Bosie’s father took his son’s homosexual relations with Wilde as a personal affront and instituted legal proceedings. Wilde was charged in 1895 with committing acts of ‘gross indecency’ with a string of young men. A handful of Savoy employees were among the key witnesses for the prosecution. Wilde was found guilty and sentenced to two years’ hard labour. Thus, the hotel lost one of its most flamboyant guests.

Albert Einstein had his own theory about the outcome of the dreadful Second World War. Over a Savoy dinner he was asked if he believed his theory of relativity to be correct. The Nobel prize winner replied: ‘There is no knowing until I am dead. If I am right the Germans will say that I am a German, and the French will say I am a Jew. If I am wrong, the French will say that I am a German.’

Austrian painter Oskar Kokoschka: ‘Here I am living on the 8th floor of the smartest hotel in Europe. I have to live this high up because from here I can paint the broadest vista of the Thames!’

Noël Coward was very particular about his toiletry articles. Every brush, comb and nail file had its place. To get the arrangements right every day, housekeeping simply took a photograph of the set-up and handed it to the butler in charge.

The Savoy archives proudly keeps early guest records of arrivals of Fred Astaire, Alfred Hitchcock, Katharine Hepburn, Enrico Caruso, Vittorio de Sica, William Holden, Marlene Dietrich, Josephine Baker and Maria Callas.

Agatha Christie: The Mousetrap – written in 1952 for Queen Mary’s jubilee (the grandmother of Queen Elizabeth II) – had developed from a 20-minute radio play into an evening-filling stage drama. Richard Attenborough and his charming wife Sheila Sim played the leads on its opening night. Producer Peter Saunders estimated it would run approximately 14 months. Ten years later, he threw a party at The Savoy celebrating the first decade of The Mousetrap. He had asked Agatha Christie to arrive half an hour early so they could discuss some details for the evening. Christie tried to go into the ballroom. An attentive assistant banqueting manager who didn't recognise her stopped the totally surprised playwright; ‘You cannot go in there, Madam. The function starts only in half an hour.’ It did indeed start and 1,000 guests celebrated with a birthday cake that weighed half a ton. And as we know, it didn’t end there. In December 2000, Sir Richard Attenborough and Jessica Spencer from the original 1952 cast celebrated the 20,000th performance with a lunch at The Savoy. Over nine million people have seen the play.

The 1960s brought us The Beatles, Bob Dylan, Yuri Gagarin – the first man in space – Kennedy’s assassination, the Vietnam war and England winning the World Cup. There was also a former chorus boy, body builder and model chosen by a Daily Express readers’ poll to play the role of Ian Fleming’s superspy, James Bond: his name was Sean Connery. Two years before his death in 1964, Fleming saw his hero on screen for the first time, hunting the evil Dr No. Sir Sean – he has since been knighted – recently combined the pleasure of staying at The Savoy with his profession, while shooting Entrapment with Catherine Zeta-Jones. One of the scenes of the film was shot at the hotel at four o’clock in the morning.

Frank Sinatra made it very clear that he would not give a concert in London unless his manager could secure him a room at The Savoy. In the event, ‘He contented himself with 15 rooms on the sixth floor,’ remembers journalist Stephen Black. His yellow guest card – kept discreetly by the unforgettable reception secretary Dodie Cotter, noted exactly where his espresso machine was stored and how many coat hangers had inadvertently slipped away with his entourage last time he had occupied the floor. Only recently, Sinatra’s daughter Nancy came to stay at The Savoy: ‘I want to stay where daddy stayed’. The same suite was prepared, decorated with hundreds of white flowers, but when Nancy entered the room, she paid little attention to all the lavish preparation and went straight to the window, opened it and sighed: ‘My father loved this view!’

Barbara Cartland recalled the London of the 1920s: ‘The Ritz stood for stuffiness and standards; The Savoy was rather fast.’

1960, Oct 14 Bing and Kathryn Crosby arrive at the Savoy Hotel in London. Bing is interviewed by Derek Hart for the BBC-TV program 'Tonight' at Sunningdale Golf Course, Berkshire. The interview is transmitted on October 19. Oct 20 At the Savoy Hotel, Bing is presented with an engraved silver cigarette case in gratitude for his large donation to a West Indian association which is forming a rehabilitation centre in London.

The Queen Mother celebrated her 90th birthday on 4 August 1990. On her birthday, her secretary reserved a table at The Savoy. When Her Majesty arrived, guests of The Savoy all joined together in a Happy Birthday chorus. Her Majesty had a splendid time at dinner and stayed until long after midnight. (All this was under the shadow of the events of 2 August, when Iraq suddenly invaded Kuwait, leading to a quick response by the Western allies.)

John Major became Prime Minister. He also fell for the private atmosphere of The Grill (indeed, he liked the restaurant so much that he and his wife regularly held their annual Christmas luncheon with his office staff there).

The most sought after party in the entire UK, perhaps the world, was recently held on a Sunday. The Savoy saw a group of young stars born and old ones confirmed. Daniel Radcliffe, Emma Watson and Rupert Grint (better known as Harry Potter, Hermione and Ron) walked into The Savoy that afternoon to attend a party of a lifetime to celebrate the release of the first Harry Potter film Harry Potter and the Philosopher‘s Stone. Dame Maggie Smith, Robbie Coltrane, Richard Harris, Julie Walters and all the other British superstars of this good attempt at turning an excellent book into a movie plus 480 guests enjoyed a reception at the Abraham Lincoln Room, followed by a dinner in the Lancaster Ballroom.

and trust us: the stories go on and on and on and ...

If you copy a story quote the source. "From the book SAVOY LONDON by Andreas Augustin and Andrew Williamson"

On the opening night of the hotel, entrepreneur and impressario Richard D’Oyly Carte confessed: ‘I extricated the hotel by great work and owing to my relations with the world of finance. I have not spoken much of it, but it was the most difficult and dangerous position in my life.’

In 1889 The Savoy was proud of its suspended lifts installed by the American Elevator Company Otis. The new lifts were all fitted with a superior safety feature, an emergency brake, making the vertical journeys smooth and pleasant. There were two ‘ascending rooms’ for guests and four for staff, and, it was eagerly pointed out, that ‘They never stop, they are absolutely safe, and the transit from earth to the realms is swift, the finest elevator service yet seen on this side of the Atlantic.’ Thanks to these lifts, the rooms on the upper floors were as desirable as those lower down and if one elected to live ‘up aloft’ one had the benefit of the better view and the cleaner air.

Speaking Tubes Although room telephones had not yet been introduced, there was a system of electric bells and ‘speaking tubes’ on each floor that were used to obtain room service. If the guest desired strict privacy, he or she could communicate with the Restaurant, and breakfasts, luncheons or dinners would arrive in no time.

The Savoy was lit throughout by electric light and the publicity boasted that ‘this Hotel was the first to introduce an all-night service of light, so that the oft-maligned man who “reads in bed” can do so with easy comfort and with no fear of setting himself, his sheets, or his fellow-guests on fire.’ There was also an ‘unfailing supply of hot and cold soft water right through the vast structure.’ The hotel’s own basement was the source of both of these modern wonders. It contained an artesian well, sunk to a depth of some 420 feet, an electricity generator, which also provided power to the neighbouring Savoy Theatre and to D’Oyly Carte’s nearby home at 4 Adelphi Terrace, as well as four huge water boilers.

A Valet For Each Guest (San Francisco Chronicle, 30 August 1891) There was quite an exciting discussion the other evening among a number of Californians at the Coleman, in which General John T. Cutting was a central figure. Some one (sic) of the Californians present had been reading in the Sunday CHRONICLE the views of General Cutting upon the superior service of the European hotels as compared with our American hostelries. Said the General, rather warming up to the situation: ‘I’ll tell you, gentlemen, that, although I only visited London and Paris, I maintain that for service there is no hotel in the United States to compare with that Hotel Savoy in London. There is no rush nor excitement when you arrive. You are courteously escorted by an attendant to your apartment, not by an officious bellboy who wants to wear his whisk-broom out on your clothes in the expectation of a tip. You open your trunk and lay out your crumpled clothes and go to your breakfast. Every wish seems to be almost anticipated, and you don’t feel like being obliged to lay down a fee for attendance. You return in the early evening to dress for dinner, and your dress suit is there freshly pressed and ironed for use. In the morning your day suit is similarly fit to wear. You couldn’t have your wants better attended to if you were at home. In fact, the hotel supplies special attendants for every want, and I never had to call for any special service—you don’t have to ring for ice water, it’s there. That’s the way to keep a hotel.’ And then there was silence, and more cigars were ordered.

Conspiring with some of the leading lights of female society, Ritz and D’Oyly Carte paved the way for ladies to attend dinners after the theatre and late in the evening. Sunday night dinner became the highpoint of the week and after theatre suppers became all the rage. If anybody expected members of the fair sex to disappear long before Cinderella’s magic hour, they were mistaken. The female clientele stayed on and it became clear how much the ladies enjoyed this welcome bridge to a new self-awareness. In 1896, Elizabeth de Grammont was reputed to be the first woman in London to smoke a cigarette in public. This she did in The Savoy Restaurant. She was on honeymoon with her husband, the Duc de Clermont-Tonnerre, who talked a lot, while she smoked a lot. The other guests stared shamelessly at this astonishing performance, expecting something extraordinary to happen. However, Elizabeth de Grammont neither exploded nor went up in flames, or even burn her lips.

The Savoy Theatre was the first theatre in the world to use electricity throughout the house. Space was reserved for orderly queues to pit and gallery, and patrons were served tea while they waited. In the first 11 years, the three partners split nearly £300,000 between them, but personal relationships became strained. Gilbert more than once quibbled over small financial matters and came to resent the warm friendship between D’Oyly Carte and Sullivan.

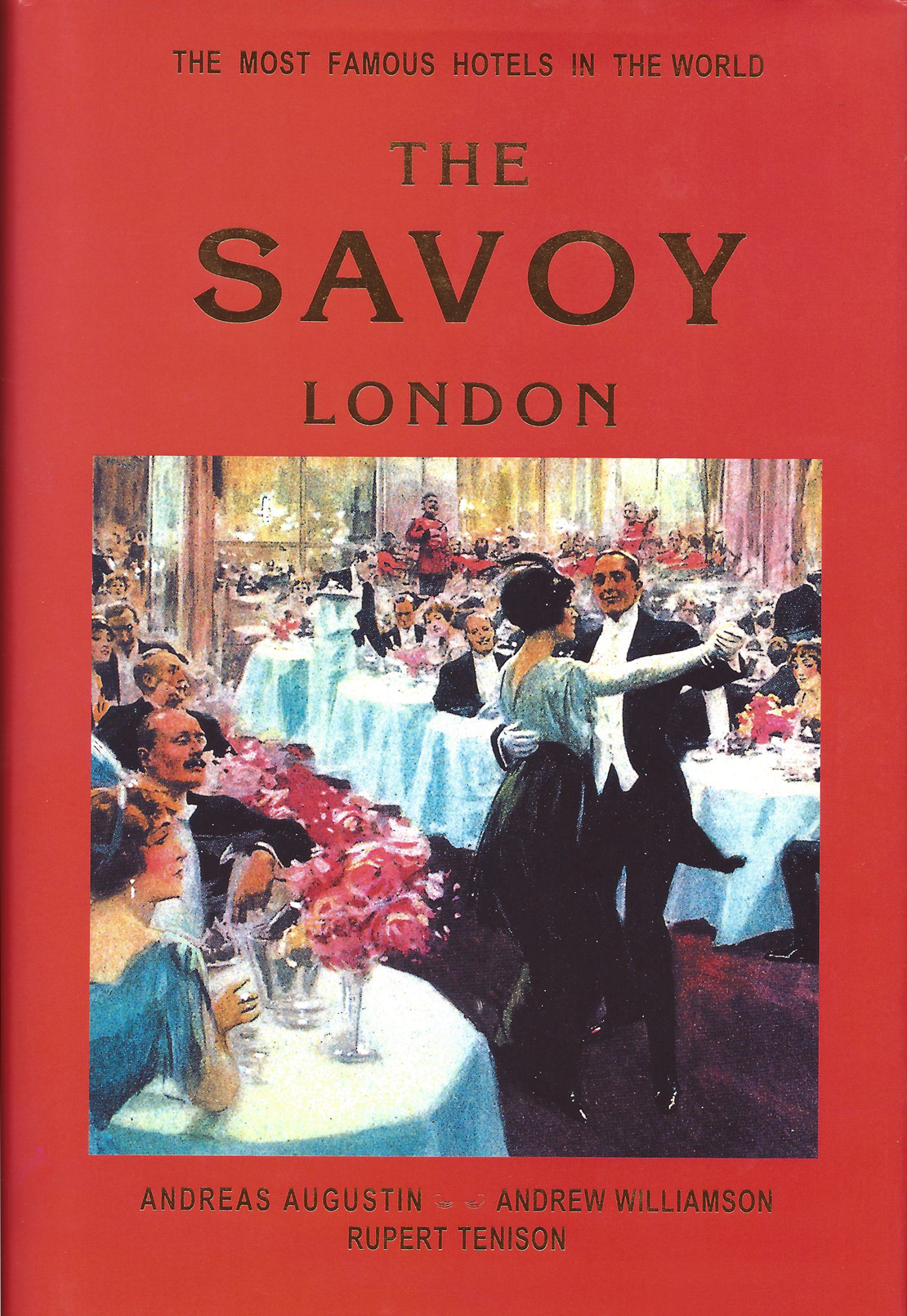

The first coloured painting of The Savoy Hotel and Restaurant in 1889 is displayed in the book. It was to the Thames that the hotel showed its most attractive face. Here were The Savoy’s public rooms. Balconies wrapped around each floor were supported by cream-coloured pillars with gilded capitals. A splash of colour was added by red-and-white striped blinds that could be drawn at guests’ leisure. The west side of the basement, now the Abraham Lincoln Room, was occupied by a ballroom, decked out in white and gold; the eastern half was split into reception and billiard rooms. The latter had ‘three full-size tables and one French table’ and was fitted out at a cost of £557 17s 3d. The room above the ballroom, today’s River Room, had originally been intended as a private banqueting room that could be hired out for meetings and dinners. It was instead converted into the Salle-à-Manger, the hotel’s fixed-price dining room. Here a plain breakfast was available for 2s, with meat or fish it cost 3s 6d, while dinner was 7s 6d. On the east side were ‘lounge-rooms, bureaus, cloakrooms, smoke-rooms, and other conveniences which are the outgrowth of modern civilisation.’

A number of concessions were provided for guests’ convenience. They included a flower stall, a ticket booth run by Keith Prowse & Co, an office of Thomas Cook & Son the travel agent and a hairdres-sing salon. D’Oyly Carte did not live to see his idea of a swimming pool and a Turkish bath realised. More delights awaited guests once they reached their rooms. It was noted that ‘The custom of residing more or less permanently, or for a certain time of the year, in Hotels, saving the trouble of housekeeping and servants, is largely increasing’ and so accommodation consisted mainly of suites of rooms. Each had a bedroom and sitting room, both elegantly furnished by Maples, and also the great luxury of a private bathroom. The ratio of 67 bathrooms to some 150 bedrooms was remarkable for the time.

The River Restaurant was ‘splendidly mounted in mahogany, carved and inlaid, and the chairs covered with red leather.’ From here, French windows opened onto a broad balcony where meals were served, including luncheon at 4s, or ‘the grateful cup of coffee and cigarette may be enjoyed in the open air.’ This unique feature of the hotel was ‘enclosed with glass and warmed in cold weather, but open in warm weather.’ The cuisine of the restaurant, it was announced, ‘is intended to be cosmopolitan. The French cuisine will naturally occupy the first position; but it is proposed to provide also purely English cooking, as well as Indian, Russian, and German dishes, while a marked importance will be given to the special products of the United States, bearing in mind the increasing number of American tourists.’

A young female guest, not used to taking no for an answer, returned from a stroll with her nanny clutching 45 yellow canaries. The birds spent the night in a cage in the girl’s room, after which she insisted on bringing them down to the more spacious confines of the foyer. She then decided that the cage was too cramped and so let them loose. The staff spent an energetic morning rounding up stray canaries, one of them having even found its way into the barber shop.

Anna Pavlova (1885–1931) danced at The Savoy in 1910. Born in St Petersburg, trained at the Imperial Ballet School and world famous for creating roles such as ‘The Dying Swan’, she began touring Europe with her own company in 1909.

Gondolas have a special place in the annals of The Savoy. Gilbert and Sullivan’s first new comic opera written after the hotel opened its doors was The Gondoliers, which premiered at the Savoy Theatre in December 1889. And the hotel’s courtyard, which had been roofed over in 1903, was turned into Venice’s Grand Canal for the legendary Gondola Dinner. Marie Louise Ritz, in her hagiographical biography of her husband, credits César Ritz with organising this landmark affair, complete with singing gondoliers, for the South African millionaire Alfred Beit. This accolade actually belongs to George A Kessler, the American representative of Moët & Chandon champagne. Kessler gave general manager Henri Pruger carte blanche to arrange something spectacular to celebrate Edward VII’s birthday in June 1905. The result was a masterpiece that quickly became part of entertainment folklore. The walls were covered with Venetian scenes; 400 Venetian lamps and 12,000 fresh carnations and roses decorated the yard; a large, stationary gondola was built to house the dining table; and the floor was flooded with water, which was then dyed a dark blue (though unfortunately it proved fatal to the swans brought in to populate the lagoon). A hundred white doves flew to freedom and a baby elephant lumbered in with a five-foot birthday cake on its back. Enrico Caruso – a declared member of the ‘Savoy Family’ – provided the evening’s musical entertainment. His fee was an imposing £450, the total cost for the evening was £3,000. Kessler added a £1,000 tip for the staff.

Melba today: pêche en Tulip à la Melba, created by Anton Edelmann It is a shame that Escoffier is best remembered for a dish of raspberry sauce poured over half a peach and vanilla ice cream. Pêche Melba was just another of his many little inspirations while Australian soprano Nellie Melba lived at The Savoy Hotel from 1892–93. Escoffier was an enthusiastic visitor to Covent Garden and the swan which appears in Lohengrin gave him the idea of preparing a surprise for the marvellous singer. The following evening, Melba had invited some friends to dinner. Escoffier had peaches served on a bed of vanilla ice-cream in a metal dish, set between two wings of a magnificent swan shaped out of a block of ice and covered with a layer of icing sugar. Only years later on the day of the opening of the Carlton Hotel in London (1898) did Escoffier decide on the sauce which was to give this dessert its real claim to distinction. He chose raspberry.

One of The Savoy’s most enduring groups is the Other Club, which was founded by Winston Churchill and F E Smith (later Lord Birkenhead) in 1911. The origins of the club are obscure. One story asserts that it was founded to meet outside the ‘real club’, the House of Commons. There are only three rules: 1) The object of the Club is to dine. 2) Nothing in the intercourse of the members shall be allowed to interfere with the full rigours of party politics. 3) The names of the members of the executive committee shall be wrapped in impenetrable mystery. It still meets once a fortnight at the Pinafore Room while parliament is in session but now includes eminent people from outside the political arena. The Other Club usually starts its gathering with a glass of champagne. The fare is rather simple: smoked salmon or dressed crab, followed by the traditional roast beef or roast lamb, and pudding. ‘Mr Vojo’ Lijesevic has had the honour of serving The Other Club for over 30 years. Mr Vojo’s personal attendance is part of the ceremony. The Princess Ida and Pinafore Rooms are always set aside to host the exclusive circle. During Vojo’s first years, Churchill still made it a point to attend as many of the 10 Thursday gatherings a year as possible. The guest list of an average of 20 arrives two days before the event and is discreetly handed over to the general manager by the secretary of the club. The manager passes it on to Mr Vojo. Nobody else knows the names, although some would like to: ‘Journalists sometimes can be very pushy, but they have come to the wrong person,’ smiles Vojo, the man from Montenegro.

On 1 July 1923, 22-year-old Ali Fahmy Bey, a wealthy Egyptian with a playboy reputation, registered at The Savoy. His stay would end tragically. Fahmy was accompanied by his French wife of six months, Marguerite. In contrast to Fahmy’s privileged background, Marguerite, 10 years her husband’s senior, was the daughter a lowly Parisian cab driver. Hers was – to say the least – a colourful life before starting the long haul up the social ladder as mistress to a string of wealthy businessmen. While accompanying her latest conquest to Egypt in 1921, she met Fahmy. After a brief relationship, the two were married. From the outset, their marriage was tempestuous. Disagreements, quarrels and arguments spiralled into emotional and physical warfare. By the time they arrived at The Savoy from Paris, Madame Fahmy had taken to sleeping with a .32 semiautomatic Browning pistol under her pillow. It was with this gun that she shot her husband in the early hours of Tuesday, 10 July 1923 outside the door to their suite on the fourth floor of Savoy Court. On the surface it was an open-and-shut murder case. But then in stepped lawyer Edward Marshall Hall for the defence. In one of the most-sensational cases of the decade, he painted a picture of Fahmy Bey as a cruel, depraved, lascivious and untrustworthy individual. His character assassination was tinged with more than a hint of racism and homophobia. Marguerite, he claimed, had acted simply to save her on life. The jury responded to its own prejudices and delivered a verdict of not guilty. Marshall Hall duly celebrated his victory at The Savoy. ------ At an after-theatre supper at The Savoy in 1913 a professional Argentine dance couple paraded down the red carpet to entertain the amazed crowd. ‘The Dance of the 200 steps – The Argentine Tango has become quite the rage in this country, more particularly in London; and this not only on the stage, but in ball-rooms and in restaurants.’

A Unique Wireless Reservation System The picture is misleading. There was no Royal Suite at The Savoy. Every guest was a king. In fact, telegraphing words cost money, so brevity was the key. A clever code was developed to transmit the desired message. Roman Emperors were usually used to represent over a dozen room combinations, e g one double and one connecting single with bath was AUGUSTUS; if you wanted a sitting room with your suite you would have cabled HANNIBAL; and to ensure your servant had cosy quarters for the night, one simply wired MARCUS. For one single with bath, for example, the message would simply have been HADRIAN. A cable received by The Savoy’s reception, saying CAESAR STOP VANDERBILT STOP and a reservation for two doubles with bathrooms and a sitting room was made in the name of Vanderbilt .

François Latry Among the men who carried Escoffier’s enduring legacy into our time, was maître François Latry (at The Savoy 1919–1942). Here he is shown in 1924, preparing a chocolate Easter egg, specially commissioned to be filled with diamonds and jewellery worth £7,000. On 12 August every year the heavily discussed grouse season starts. For over a century, The Savoy and The Connaught have prided themselves on being the first hotels in London to have the birds in the oven. In the old days, a page boy raced to the station to pick up the birds.

The Indian princes, the maharajas and the Nizams, made their annual pilgrimage to London for the Season. The Maharaja of Patiala came with a large retinue that included a personal chef, private secretaries, chauffeurs and bodyguards who spent the night curled up outside their master’s bedroom. The buffets for his dinner parties were adorned with elephants and camels, sculpted in ice. Below: The Music Hall Ladies’ Guild celebrates in style and costume. ‘When we celebrate at The Savoy, we are always in larger numbers. Families seem to triple by the time the invitation is delivered. You see, money is relative. The more money, the more relatives!’

A famous historic hotel is always steeped in anecdotes, half true in the beginning and well embroidered by the end, diligently passed down by countless generations of managers, headwaiters and cloakroom attendants. One of the Savoy favourites was spun by the late Marie Louise Ritz, the widow of César Ritz. According to this legend, César Ritz, who managed the hotel at the beginning, engaged Viennese ‘king of the waltz’ and bandleader Johann Strauss to perform in the hotel’s restaurant. Unfortunately, we are unable to confirm this legend as Strauss was last known in London in 1867, 21 years before the Savoy opened for business.

The hotel’s most-frequent diner is a wooden cat called Kaspar. This friendly feline was created from a single piece of plane tree in the 1920s from a sketch by Basil Ionides, who also did the decorative designs when The Savoy Theatre was rebuilt in 1929. Whenever 13 dine in the hotel, Kaspar is called upon to even up the numbers. He duly takes his place around the table where, with a napkin tied around his neck, he is served the full complement of courses. The origin of this custom is said to date from 1898. The mining magnate Woolf Joel gave a dinner party prior to returning to South Africa. A last-minute cancellation meant that only 13 sat down to the feast. The old superstition that the first to leave a table of 13 people would be the first to die proved tragically true. Joel was shot by a blackmailer shortly after his return to the Cape. After that, a member of staff was recruited to make up the numbers but this proved intrusive and so Kaspar was born. -------- The Savoy’s resident bands became known to an international audience thanks to their association with the fledgling British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC), the hotel’s neighbour on Savoy Hill founded in 1922. On 13 April 1923, Bert Ralton’s Savoy Havana Band made its first live broadcast from the hotel. It was joined in September by the newly formed Savoy Orpheans under Debroy Somers and, together, they became household names in England. In October 1923, ‘Dance Music from The Savoy Hotel in London’ was first broadcast over the crackling airwaves. Millions tuned in their crystal radio sets, cleared rugs from floors and danced to the music of Ralton and his Havana Band and to the Somers Orpheans. The Orpheans had an average weekly audience of 2.5 million and they sold more than 3 million records worldwide. It was hard to say who was the star of the show when guest George Gershwin joined the band on the ivories and treated London to the first airing of his Rhapsody in Blue.

Just checking Charlie Chaplin and his family occupied the same suite virtually every year for four weeks in August. In his book Hotel Reservations, Derek Picot (at that time assistant manager) recalls a story about a receptionist. The young man was anxious to meet Chaplin and made sure that he was on duty when the living legend arrived. On the great day Chaplin, now Sir Charles – confined to a wheelchair – was wheeled into the lobby by a nurse, Geraldine and Lady Oona following behind. The assistant manager brought them up to their room and went into every possible detail so as to spend as much time as possible in the presence of his idol. Chaplin and the family weren’t in the mood for talking. The assistant manager went on and on with useful explanations ‘This is your TV set. This is a bedroom, here is your bathroom, may I show you how to turn on the hot water?’ until he finally sensed that his presence wasn’t welcome. He decided to cut short his dissertation on the hotel’s amenities and left, with a discreet bow, through one of the four identical doors into their sitting room. As he closed the door the light went out. It slowly dawned on him that he was not in the sitting room but that he had taken the wrong door and was between the communicating doors to the next suite along. In the tradition of the establishment, he did not panic. It didn’t take him long to find out that there was no keyhole to any of the doors. He took a step back and in the darkness hit his head on a moveable object. It swung back and hit him again. He realised; ‘if that was a coat hanger, then this must be the wardrobe.’ The situation was resolved in true Savoy style. Instead of panicking, he left the wardrobe after one solid minute of strategic planning. The silence outside nourished his hope that the Chaplins had all gone to the next room. To his horror, there they all were, gathered together as if sitting for a family portrait, their faces turned to the wardrobe and their unanimous expression far too easily translatable as: ‘You incompetent cretin.’ ‘Just checking,’ the young man mumbled and – taking the correct sitting room door – he disappeared.

The Savoy received a letter from Czechoslovakia addressed to ‘The Greatest Hotel in London’. The postmaster suggested ‘Try Savoy Hotel WC2’. He was right. Decades later, The Savoy’s marketing department had this skilful photograph taken. It was used in an advertising campaign saying: ‘Nowadays, people tend to use our Internet address.’

The Grill – sandwiched between the residential suites and the lobby, with its main entrance off Savoy Court – was called the Café Parisien. With its Garden Terrace for summer use, it was quickly adopted by the business, press, literary and theatrical worlds for their working lunches and post-theatre celebrations. It was hailed as very French. One guest, however, joked: ‘Everything at The Savoy is French except the prices. They are tropical and grow to a great height.’

At the Grill's early days, the guestlist included Louis Mayer and Samuel Goldwyn, Harry Warner and Adolph Zukor, Joe Schenck and Marcus Loew and directors such as D W Griffith, one of the founders of United Artists. For the nostalgic, there was the chance to spot Louis Lumière, the film pioneer and in a corner of the restaurant Austro-Hungarian-born composer Franz Léhar sipped his Tokay. Olivia de Havilland lunched here. She was discovered in Hollywood by Max Reinhardt, who loved to eat at The Grill with Eveline Leigh. A P Herbert discussed the improvement to the divorce law with Lady Diana Cooper. Chansonnier Maurice Chevalier dined on plain English fare, struggling for physical fitness and to kick his habit of at least 50 cigarettes a day. The Queen of Yugoslavia dined at The Grill on smoked turkey and smoked salmon and took a large hamper with her back to wartime Yugoslavia. Vivien Leigh, born in Darjeeling, and Laurence Olivier, born in Dorking, met at The Grill of The Savoy and fell in love. Auguste Laplanche, a Norman, arrived shortly after the end of the war and was maître chef at The Grill for almost 20 years. The lovely Paulette Goddard, wife of All Quiet on the Western Front Erich Maria Remarque and ex-wife of Charlie Chaplin, cheerfully admitted to having a hearty appetite and used to ward off hunger pangs during the night by hoarding provisions in her dressing-table. Siegfried Sassoon, T E Lawrence and arch-critic Hannen Swaffer, Lord Beaverbrook, Noël Coward and Gertrude Lawrence were always the centre of attention. Playwright Coward would come by after a show, have a glass of wine and a bowl of bouillabaisse laced with garlic. At the Savoy Theatre, his Broadway musical Sail Away ran for 252 performances, several weeks longer than in New York. A decade earlier, in 1951, he had given The Savoy a rousing hit with his comedy Relative Values. Greta Garbo, the cool Swede, lunched here under a sombrero, H G Wells and Gerald du Maurier came here for lunch, as did Somerset Maugham (perhaps it was The Savoy that changed his belief that ‘To eat well in England, you must have breakfast three times a day’). In 1962, maître chef Abel Alban retired from The Grill after 40 years of faithful service. His successor was Silvino Trompetto, the first London-born maître de cuisine of The Savoy. One night, General manager Griffin asked Sir Winston Churchill what he had thought of the dinner prepared with greatest care by Trompetto. Sir Winston didn’t reply immediately. Griffin thought there was something very wrong. After a while, the great statesman sighed and said: ‘When I die, and if I have a choice, I’d rather have The Savoy staff looking after me in heaven instead of angels.’

Of course, it was not always plain sailing in British hospitality waters. The Savoy sits at the top of many shopping lists. Some offers were appreciated, some less so. Conrad Hilton expressed an interest in adding The Savoy to his chain of hotels. (He clearly had a soft spot for historic grand hotels. The group acquired the Waldorf-Astoria in New York and, more recently, manages the historic Langham and GWR Paddington in London). The Savoy’s board of directors was able to respond amiably that they were not too enthusiastic about the idea. An unwelcome takeover attempt was fought off by Sir Hugh when Charles Clore and Harold Samuel tried to acquire the majority of the shares in 1953. Shortly after that Sir Hugh created a new share system that would prove most helpful in the future. A serious takeover attempt was made in 1971 by Trafalgar House (Nigel Broakes and Victor Matthews) and in 1981 by the famous Forte family. Wontner successfully fought off the bid by pulling his system of A and B shares out of a magic hat*. Forte Hotels had to learn that it had indeed acquired a very dominant ownership position financially but was in fact powerless in the boardroom due to a two-tier share structure. Now the splitting between the ineffective A shares and the powerful B shares made sense. The A shares served to give the public participation in the nations most legendary hotel group, but only limited voting rights, which were heavily weighted to the B-share owners. The takeover did not take place. Looking back, stock specialists express serious doubts as to whether such a manoeuvre would be possible today. Later, the Forte family lost all their Savoy shares to Granada in a successful hostile takeover bid, which led to Gerry Robinson taking a seat on the board and playing a role in guiding the ship back to private ownership. * In a vote, the 10p A shares carried one vote for each £1 in nominal amount; the 5p B shares carried 10 votes for each 25p in nominal amount.

TRAINING: Olive Barnett had joined The Savoy in 1928 and was awarded an OBE in 1981. It was she who interviewed Hugh Wontner for a job at The Savoy and recommended him as a ‘quite promising young man’. In 1966, she was instrumental in setting up the elite Professional and Technical Training Department of The Savoy Group in a building adjacent to The Berkley Hotel. This programme was considered the best training in the industry and became a testament to The Savoy’s contribution to training and developing management all over the world. Since 1975, the Savoy Gastronomes (see page 212) offer the ‘Olive Barnett Award’ to motivate young trainees. The five-year management scheme included one month of ‘meat’ and one month of ‘flora’ (fruit and vegetables; getting up at 4am, going to the market at Covent Garden, etc.), the rest of the first year was devoted to the kitchen, six months to the bar, one year to offices, one year abroad (especially to improve students’ French) and one year of front office. There was also a special ‘Savoy English Course’ by Basil Lord and Michael Coles. Today, The Savoy’s educational tradition is continued by its sister organization, The Savoy Educational Trust (SET), under the management of Julia Sibley. This independent charitable trust was established in 1961, receiving a pack of valuable B-shares as financial backing. When the company was sold in 1998, the SET realised its share for £38.5m, which gave it solid working capital to support the educational needs of the UK’s hotel management future. ------- As the traditional playground of mixed political parties, The Grill is nicknamed ‘the second House of Lords.’ In the 1960s, the maître d’hôtel used to ring a bell when the members of parliament had to go back to vote. The Grill is closed in August, when parliament has its summer break.

Rudi Schreiner, reception manager in the 1970s and later general manager in Vienna, remembers a particularly attractive singer who was on stage during the days of supper cabaret at the Thames Foyer. When she began a particular number from Cabaret, all the guests would stare at the stage. When she came to the bit which requires a fair degree of upper torso movement while singing ‘Money money money . . . money money money . . .’, followed by a sound on the cymbal denoting an imaginary silver coin falling into her juggling cleavage, everyone was spellbound… Absolutely everybody, including the young waiter who was serving a large table of fourteen right next to the stage. Unfortunately, although he hadn’t put out any plates, he calmly started to serve the main course straight onto the tablecloth. Apparently no one noticed until the gravy was poured.

On 20 August 1989, 51 people lost their lives when the dredger Bowbelle collided with The Marchioness pleasure boat almost in front of The Savoy. A great number of wonderful young people were killed – the average age of those who died was 25. The Savoy, being the nearest possible place, offered its parlour and ball room as a temporary shelter. That night all the joyful moments those halls had witnessed during their first century were overshadowed by overwhelming hours of grief and sorrow.

Wimbledon is heralded at The Savoy by the ‘Cream of Strawberry Teas’. The Wimbledon Champions’ dinner is the highpoint of these two weeks of strawberries and cream. Here different challenges are met. The strategy is to have the correct flag standing behind the champion. Although the hotel has a collection of flags in store, sometimes extra flags need to be ordered. If there are two Germans in the semi-finals on Thursday, the banqueting department stands a fair chance of needing a German flag or two on Sunday. And hopefully a Union Jack in the near future.

Gastronomes and Society In 1971, The Savoy Gastronomes were founded to foster the spirit of the Savoy reception and to recognise the tutorship and guidance given to Savoy receptionists by Nicholas St. John Brooks who was for many years reception manager. Only those who have completed 9 months at Savoy reception can join. Today the organisation has 300 members in 44 countries, organizes The Savoy Gastronomes Olive Barnett Award, offers a club tie and scarf and an annual black tie reunion in such diverse locations as St Petersburg, Moscow, Jerusalem, New York, Paris, The Hague, Geneva, on board the QE II and many other sensational places. The Savoy Society was formed in 1990 under the aegis of the late Sir Hugh Wontner, to be a point of contact for former employees of the Savoy Group of Hotels & Restaurants. Membership of The Savoy Society enables friends and former colleagues to meet in a sociable environment to discuss matters of mutual interest. There are over 200 members.

Shower Power The 290-hole shower-heads provide a sensational jet of water (the shower-heads at The Savoy are connected via a 3/4“ British standard pipe thread and require 4bar or 56lbs of water pressure to maintain the required volume). The large-bore pipes fill the bath tub in thirty seconds, overflowing in thirty-five. Rod Steiger was just one of the many guests who ordered one of the shower-heads. Some simply unscrew and steal them. Sir Elton John can tell a story about the extraordinary water pressure in The Savoy: he turned the bathtaps on and went to the sitting room to make a telephone call. While he was on the telephone, the bath overflowed, pouring water into the suite below where composer Marvin Hamlisch was staying, and then below that, where Michael Parkinson and his wife were staying. They say it ‘never rains ...’

and so on. If you copy a story quote the source. "From the book SAVOY LONDON by Andreas Augustin and Andrew Williamson"

Entrapment with Catherine Zeta-Jones and Sean Connery was partially filmed at the hotel.

The Savoy Hotel

GENERAL MANAGERS in HISTORY

Hardwicke, William July 1889–December 1889

Ritz, César December 1889–March 1898

Robarts, H B March 1898–February 1899

Mengay, Henri February 1899–December 1900

Collins, W D January 1901–August 1903

Pruger, Henri November 1903–September 1909

Seggelke1, Gustave October 1909–July 1912

Blond, Marcel August 1912–December 1914

Soi, G January 1915–December 1919

Gelardi, G January 1920–January 1924

Graedel, H W February 1924–January 1926

de Bich, Clement January 1926–February 1928

Gilles, A March 1928–December 1940

Hofflin,W A January 1941–October 1960

Griffin2, Beverley H November 1960–June 1971

Contarini, Paolo January 1961–November 1971

Griffin, Beverley H November 1971–October 1978

Buttafava, Claudio C November 1978–December 1981

Bauer, Willy B G December 1981–June 1989

Striessnig, Herbert June 1989–April 1995

Palmer, Duncan Roderick June 1995–September 1997

Shepherd, Michael September 1997-2002

2002 Jean-Jacques Pergant

2004 Daniel Mann

2005 Mark Huntley

2006 Kiaran MacDonald

1 Also listed in one old list as Seggletz, but Seggelke is the correct version. ?

2 Mr Griffin and Mr Contarini were joint managers between January 1961and November 1971.

152 Rooms

50 Suites

The River Suites overlooking Thames River are world famous. ------ The hotel also boasts charming and practical family suites.

Between Victoria Embankment (the Thames River) and the famous Strand (a street's name), five minutes walk to the opera house "Covent Garden", in the heart of the theatre district.

Oscar's (former River Restaurant), American Bar, Thames Foyer, The Upstairs Champagne and Seafood Bar, The Grill Room (see Scandals, Stories and Legends)

The American Bar is a legendary institution at The Savoy. Although State-side visitors joked that the name ‘American’ indicated that they served chilled Martinis or – as some others suggested – that ice in general was actually served with the drinks, it was more a generic term for a bar specialising in mixed drinks. It had existed in various guises and locations since The Savoy’s earliest days. A booklet handed out to guests in 1893 proudly announced that room service could provide ‘anything from a cup of tea to a “cocktail” from the American Bar.’ From 1903, the bar was in the capable hands of Ada Coleman. She had started working at the bar of the newly reopened Claridge’s in 1899 before moving over to The Savoy. Coleman’s most famous gift to the cocktail world was the Hanky Panky, invented for Sir Charles Hawtry. The crusading prohibitionist William Eugene ‘Pussyfoot’ Johnson went back to America after his attempt to talk England dry – he lost an eye when he was struck and dragged from a lecture platform in London by medical students. Now the term ‘American Bar’ took on a new meaning when Prohibition in the States sent Americans flocking abroad in search of a proper drink. In their vanguard were the out-of-work bartenders, including the American Bar’s high priest of pre-WWII days, Harry Craddock. When he arrived at the hotel in 1920, the bar had displaced the reading and writing rooms to take up its now-familiar place off the lobby. Craddock’s creations included the Strike’s Off to mark the end of the General Strike of 1926. His most enduring testament to the cocktail age was The Savoy Cocktail Book, first published in 1930. It has become an essential reference work for mixers and shakers.

More figures? In an average year, the restaurants at The Savoy see the following: 25,000 bottles of champagne uncorked, 830kg of caviar served on crushed ice, 14t of Scottish smoked salmon sliced, 3,000 Dover soles grilled, 39t of French butter used, 2t of Strasbourg foie gras served, 6,000 portions of beef and 5,000 of lamb carved at the trolley and half a million English oysters consumed. All this doesn’t include banqueting, of course!

Tea at the lobby ------ Breakfast at the River Room overlooking the Thames River ------ A drink at the American Bar

Fitness Gallery, Sauna, Steam rooms, Swimming pool