New York: Washington Square, Ansonia, Wolcott

( words)

1. The Washington Square Hotel

A haven for writers and artists for more than a century, the Washington Square Hotel, located at Waverly and MacDougal, just off the northwest corner of Washington Square, occupies a unique place in Greenwich Village’s history. The hotel facilities include 150 guest rooms, a renovated lobby, 24-hour front desk service, fitness room, lobby bar and the highly acclaimed North Square Restaurant & Lounge. Complimentary wireless internet access is available in the lobby and lobby bar.

The Washington Square hotel was built in 1902 as a residential hotel named the Hotel Earle after its first owner, Earle S. L’Amoureux. The hotel occupied a single, eight-story, red brick building on Waverly Place, in the heart of Greenwich Village, now an historic landmark district. In 1908, L’Amoureux built an identical connecting building to create a grand apartment hotel, complete with reading rooms, restaurant and banquet facilities. Four years later, he added a ninth floor and, in 1917, he acquired an adjoining three-story building, bringing the hotel to MacDougal Street, at the northwest corner of picturesque Washington Square.

In the 1930s, Knott Hotels, one of the nation’s first hotel chains, owned and managed the Earle and advertised:

American Plan* from $3.50 single, $7.00 double

European Plan* from $2.00 single, $3.50 double

This was time of great change for the neighborhood. Once a staid, affluent community (as depicted in Henry James’ Washington Square and The Heiress), Greenwich Village was becoming the center of New York’s bohemian counterculture, reflected by the Beat generation who gravitated to the coffee houses and jazz clubs. The once-grand hotel was allowed to deteriorate into a shabby apartment hotel, making it an affordable location for struggling artists, actors, writers and musicians.

Ernest Hemingway stayed at the hotel for a few weeks in 1914, just before he went off to serve in World War I. Joan Baez, Bob Dylan, Bill Cosby, Barbra Streisand, the B-52’s, Maynard Ferguson and Bo Diddley have all been guests at the hotel.

In the 1950’s, Dylan Thomas and his wife Caitlin were evicted from the Beekman Hotel after, legend has it, the management got tired of his partying and excessive demands on room service. Seeking residence close to one of his favorite bars in Greenwich Village, the Minetta Tavern, Dylan checked into the Hotel Earle, then a somewhat well-worn hotel, with an easygoing atmosphere and staff.

He wrote a letter to his parents in May 1950 in which he described the Earle as “right in Washington Square, a beautiful Square, which is right in the middle of Greenwich Village, the artists’ quarter of New York.” In 1973, the Daniel Paul family purchased the hotel and began the process of upgrading the property. They converted the residential hotel into a transient facility, catering to both domestic and foreign travelers. They renamed the hotel in 1986, to reflect the proximity of the historic Washington Square, and the importance of the surrounding landmark neighborhood. In 1992, Judy Paul opened North Square Restaurant, a first-class New York bistro at the hotel. More recently, Judy Paul and her husband Marc Garrett have renovated the hotel as an uncommonly attractive boutique facility. It has unique and colorful tiles and paintings designed by Rita Paul.

The restaurant has large picture windows overlooking Washington Square Park which bathe the room with sunlight. A huge bouquet of fresh-cut flowers creates a warm welcome, as does the breadbasket loaded up with a selection from Amy’s Bread and Pain d’Avignon. The restaurant serves breakfast, lunch and dinner. They never close for breakfast, remaining open 365 days a year. On Sunday afternoons, they do a jazz brunch. A few years back, one of the breakfast waitresses asked if they’d let her perform. She gave them a demo CD to listen to. The Pauls were impressed and gave her the green light. She went on to win five Grammy Awards. That waitress was Norah Jones.

The Washington Square area is the soul of downtown Manhattan, alive with music venues, stylish restaurants, trendy clubs and distinctive shops. The adjacent neighborhoods of Little Italy, Chinatown, the East Village, West Village, Soho, Tribeca, the Meatpacking District and Chelsea are all within easy walking distance. In addition, New York University, Cardozo Law School, Cooper Union and The New School University are just steps away from the hotel’s front door.

2. The Ansonia Hotel

The Ansonia was built as a luxury residential hotel on the upper west side of New York in 1904. Its resplendent apartments contained multiple bedrooms, parlors, libraries and formal dining rooms with high ceilings, elegant moldings and bay windows. The hotel had a central kitchen and serving pantries on every floor so that residents could enjoy meals prepared by professional chefs. The original Ansonia also had tearooms, restaurants, grand ballroom, Turkish baths and a lobby fountain with live seals.

It was originally built by William Earle Dodge Stokes, the Phelps-Dodge copper heir and it was named for his grandfather, the industrialist Anson Greene Phelps. In 1899, Stokes commissioned architect Paul E. Duboy to build the grandest hotel in Manhattan.

In what might be the earliest harbinger of the current developments in urban farming, Stokes established a small farm on the roof of the hotel. He had a Utopian vision for the Ansonia - that it could be self-sufficient, or at least contribute to its own support - which led to perhaps the strangest New York hotel amenity ever. “The farm on the roof,” Stokes wrote years later, “included about 500 chickens, many ducks, about six goats and a small bear.” Every day, a bellhop delivered free fresh eggs to all the tenants, and any surplus was sold cheaply to the public in the basement arcade. Not much about this feature charmed the city fathers, however, and in 1907 the Department of Health shut it down.

The Ansonia has had many celebrated residents, including the baseball player, Babe Ruth; the writer, Theodore Dreiser; the conductor, Arturo Toscanini; the composer, Igor Stravinksy; and the Italian tenor, Enrico Caruso, who chose the hotel to live in because of its thick walls.

- A key player in the 1919 Black Sox scandal, first baseman Chick Gandil, had an apartment at the Ansonia. According to Eliot Asinof, in his book Eight Men Out, Gandil held a meeting there with his White Sox teammates to recruit them for the scheme to intentionally lose the 1919 World Series.

- Willie Sutton, the bank robber, was arrested at Childs Restaurant in the Ansonia.

- The Ansonia housed an infamous gay bathhouse, the Continental Baths, in its basement during the 1960s and 1970s. In 1977, the club became Plato’s Retreat, a heterosexual swing club. Bette Midler started her singing career at the Continental Baths with Barry Manilow as her accompianist.

- The Ansonia was also used as the apartment building where Bridget Fonda and Jennifer Leigh lived in the 1992 film Single White Female. The apartment scenes were filmed in a studio but the stairwell scenes were filmed on location at the hotel.

- In the Neil Simon film, The Sunshine Boys, the character Willie Clark, played by Walter Matthau, lives in the Ansonia.

- In the film, Perfect Stranger, Halle Berry plays a news reporter who lives in a “professional-decorated $4-million condo in the lavish Ansonia building on the Upper West Side.”

By the mid-20th Century, the grand apartments had mostly been divided into studios and one-bedroom units, almost all of which retained their original architectural detail. After a short dispute in the 1960s, a proposal to demolish the building was fought off by its many musical and artistic residents.

In 1992, the Ansonia was converted to a condominium apartment building with 430 apartments. By 2007, most of the rent-controlled tenants had moved out, and the small apartments were sold to buyers who purchased clusters of small apartments and combined them to recreate the grand apartments of the building’s glory days, with carefully-restored Beaux-Arts details. The building is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

3. The Wolcott Hotel

Although it opened on March 1, 1904, the Wolcott remains one of New York City’s best-kept hotel bargain secrets. Centrally located on 31st Street, just 3 blocks down Fifth Avenue from the Empire State Building, the Wolcott was designed by one of the most famous architects in the United States, architect John H. Duncan. He came to prominence in the early 1890s when he designed Ulysses S. Grant’s Tomb and townhouses for some of New York’s richest families. Duncan’s bold Beaux-Arts style was evident in his designs for the Wolcott. The Architects’ and Builders’ Magazine (September 1903) took note of the hotel’s “elaborately sculptured (exterior) decoration” and reproduced detailed drawings for ceiling design, window treatment, the neo-Greek vestibule and Louis XVI-style restaurant.

Unlike many 100 year-old hotels, the Wolcott’s interiors are remarkably intact: mosaic floors, crown moldings, stained glass and ornamental iron.

The original developer William C. Dewey had a shady past. It was reported that, as president of a Massachusetts carpet company, he was arrested in 1890 for obtaining $900 in goods from a New York vendor without the ability to pay and he spent at least one night in the Ludlow Street jail. Nevertheless, he was able to enter the real estate and hotel development business, which ultimately resulted in the construction of the Wolcott Hotel. After a delayed opening, Dewey leased the hotel to Colonel James H. Breslin (Gilsey House, Manhattan; Brighton Beach Hotel, Brooklyn; Auditorium Hotel, Chicago). By 1905, the American Mortgage Company took back the building and Dewey retired in obscurity. James Breslin’s lease was undisturbed and he moved into the hotel when it opened.

The 1915 census shows the employees who lived-in at the Wolcott: two cooks, eleven maids, two glass maids, a pantry girl, head cleaner and eleven cleaning women. The Corning Glassware Company used the Wolcott Hotel’s kitchen in 1908 to test its new ovenware; Corning salesman William Thompson’s father-in-law was the Wolcott’s general manager at the time.

Surprisingly, not much has changed on the street floor in the past 106 years. An original plan shows the lobby in its present location with the office on the right side and the lobby extending to the rear under a musician’s gallery (which still survives) into the restaurant at the rear. The ground floor had a ladies’ reception room and a café with a leaded glass ceiling at the front and a smoking room, children’s dining room and Palm Room on the sides. The Louis XVI-style lobby had tall French mirrors, mahogany chairs upholstered in green velvet with the hotel’s crest embroidered in gold. The Palm Room’s ceiling was stained glass over a trellis of vines, “giving the effect of being open to the sky.”

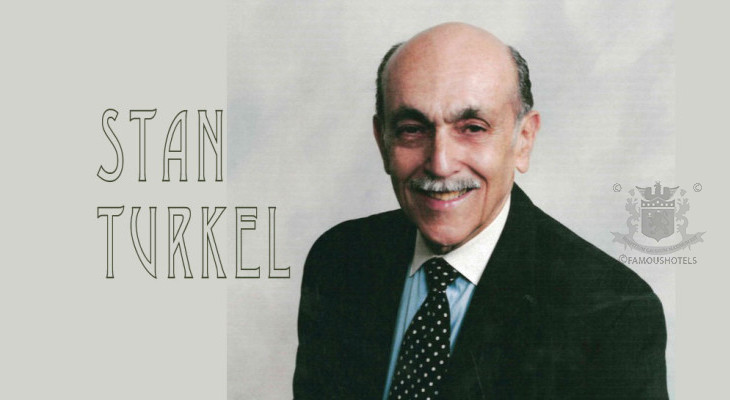

The perfect gift book for 2010:

Stanley Turkel has just published “Great American Hoteliers: Pioneers of the Hotel Industry.” It contains 359 pages, 25 illustrations and 16 chapters devoted to each of the following pioneers: John McEntee Bowman, Carl Graham Fisher, Henry Morrison Flagler, John Q. Hammons, Frederick Henry Harvey, Ernest Henderson, Conrad Nicholson Hilton, Howard Dearing Johnson, J. Willard Marriott, Kanjibhai Patel, Henry Bradley Plant, George Mortimer Pullman, A.M. Sonnabend, Ellsworth Milton Statler, Juan Terry Trippe and Kemmons Wilson. It also has a foreword by Stephen Rushmore, preface, introduction, bibliography and index.

Visit www.greatamericanhoteliers.com to order the book.

* The European Plan, sometimes abbreviated as EP in hotel listings, indicates that the quoted rate is strictly for lodging and does not include any meals. All food provided by the hotel is billed separately. Taxes and tips are usually additional as well. Some hotels offer guests the option of being on the American Plan, a Modified American Plan, a Continental Plan, or the European Plan. The advantage of the European Plan is that it encourages guests to try a variety of restaurant experiences, and they can often save money by eating at establishments that charge less than the hotel dining room.

The Continental Plan, sometimes abbreviated as CP in hotel listings, indicates that the quoted rate includes a continental breakfast. A continental breakfast normally consists of coffee or tea, juice, and bread. The bread may be as simple as a loaf or as appealing as a basket of freshly baked croissants, scones, and muffins. At some facilities, yogurt and fresh fruit may also be available. The Continental Plan breakfast does not include cooked foods, such as pancakes or eggs.

The American Plan, sometimes abbreviated as AP in hotel listings, means that the quoted rate includes three meals a day, i.e. breakfast, lunch, and dinner. In the American plan, the meals are provided by the hotel kitchen.

Some hotels offer guests the option of being on the American plan or paying a la carte for food consumed in their facility. Travelers choosing a hotel in a remote location where there are not many restaurants — or none at all — need to stay at a hotel that offers an American plan. In Europe this plan is simply called "full board".