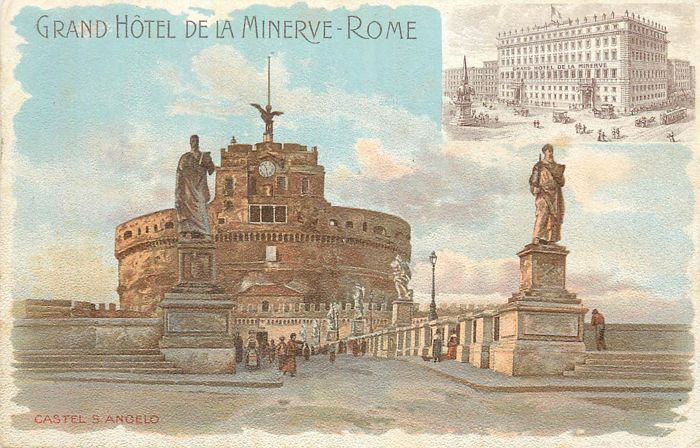

Mourby of Rome — Hotel Minerve

( words)

The view of Rome from the rooftop terrace of Grand Hôtel de La Minerve is justly celebrated. In 1917 Pablo Picasso, Jean Cocteau and Picasso’ s future wife Olga went up there to take photos.

At the time Picasso and Cocteau were staying at Grand Hôtel de Russie during the tour of Diaghilev’s new surrealist ballet Parade. Eric Satie had written the music, Cocteau had created the scenario and Picasso the costumes. The Russian dancer Olga Khoklova was a member of Diaghilev’s company and from the many pictures taken of her that day she had obviously captivated Picasso. The couple married the following year.

Some of these photographs are currently on display in the hotel’s lobby and they show that in 1917 the roof terrace had the same short brick pillars and metal balustrade that are up there today. Nowadays this nineteenth-century addition to the hotel is called the Minerva Roof Garden. In good weather it’s swathed in canopies and white table cloths and served by its own cocktail bar.

Some of these photographs are currently on display in the hotel’s lobby and they show that in 1917 the roof terrace had the same short brick pillars and metal balustrade that are up there today. Nowadays this nineteenth-century addition to the hotel is called the Minerva Roof Garden. In good weather it’s swathed in canopies and white table cloths and served by its own cocktail bar.

The view however is unchanged. As I sat up there waiting for the sunset I could see the gently curving roof of the Pantheon rising on the one side of Piazza della Minerva and the spire of Borromini’s Sant'Ivo alla Sapienza – if ever there was a masterpiece of Roman Baroque architecture this it – rising on the other. Meanwhile immediately below stood the Church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva, built directly over foundations of a temple dedicated to the Egyptian goddess Isis (and erroneously ascribed to Minerva by the Dominicans).

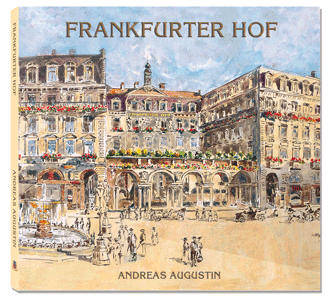

With so much architecture going on below it’s all too easy to neglect the Grand Hôtel de la Minerve itself . This substantial building, the size of an entire city block, was one of Rome’s earliest grand hotels. It was built in 1620 as a palazzo for the Fonseca family, aristocrats of Portuguese origin. During the French Revolution of 1789, a local aristocrat Princess Massimo, widow of the Roman duke Federico Cesi, took refuge here fearing the spread of mob violence.

In 1810 a French hotelier called Joseph Sauve took the palazzo over and converted it into a hotel. At this time Rome was part of Napoleon’s French Empire, administered as Département Rome. After the Fall of Napoleon, in 1815 the département ceased to exist and the Pope was reinstated as Rome’s ruler at the Congress of Vienna. Sauve’s hotel remained in operation, and was even enlarged, with an extra floor added at some point during the nineteenth century, giving us the current panoramic roof terrace.

The scene was set for the arrival of the hotel’s most important visitor. Not Picasso, who only visited, but Stendhal, the French author. He stayed for two years and actually wrote some important works in Grand Hôtel de La Minerve.

Stendhal (real name Marie-Henri Beyle) was a remarkable man, an essayist, novelist, autobiographer and egotist. Born in 1773 he had - according to his own unreliable memoirs - joined Napoleon’s army at the age of and in 1813 he had survived the long march out of Russia.

In 1814 after the Treaty of Fontainebleau, Stendhal left France for Italy, where he served as French consul at Trieste and then in Civitavecchia, the main port for Rome.

In the 1830s he resided in the centre of this city, claiming various addresses, not all of them credible. However we do know that between 1834 and 1836 he lodged at the hotel in Piazza della Minerva (by this time it was known as Palazzo Conti after the new owner, Giuseppe Conti).

Hotels have always changed their names, usually to announce a new owner or to attract a new market. After Stendhal’s time, in the heady years following Italian Unification in 1871, Palazzo Conti was renamed Hôtel Minerva-Cavour e Francia. In the twentieth century it was briefly Crowne Plaza Minerva before becoming Grand Hôtel de La Minerve as it is today.

Stendhal clearly loved Rome. In his idiosyncratic essay On Love (published in 1822) he compared the "birth of love" unfavourably to the city of Bologna but the “achievement of love” he saw as analogous to Rome. To Stendhal Rome represented the consummation of perfect love. He even drew a diagram to explain how one progressed metaphorically from one to the other.

While living at the hotel and working as consul in Civitavecchia Stendhal began his second major novel, Lucien Leuwen but he abandoned it out of fear that its Bonapartist politics might cause him to lose his government position. Stendhal considered King Louis-Philippe’s July Monarchy in France repressive. Lucien Leuwen was published posthumously in 1894. Stendhal also began his autobiography, Vie de Henri Brulard at the hotel. We even know the date he started it, 23 November 1835 but he abandoned this book too and it was only published in 1890 – to great acclaim.

Today the hotel that saw the commencement of these two important works of French literature commemorates Stendhal’s sojourn in a Stendhal Suite that is tucked behind reception and up a small flight of stairs. There is no reason to believe that Stendhal stayed in this exact sequence of rooms but they are remarkably and imaginatively preserved with arched and frescoed ceilings – a very different style from the rest of the more modern hotel. There is also a delicious view of Bernini’s elephant from the bedroom window.

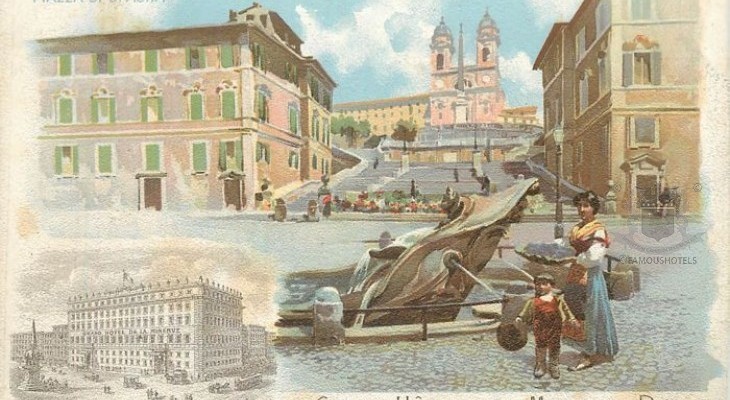

Gian Lorenzo Bernini’s elephant is an odd piece of Roman Egyptiana and once you’ve seen it you’ll never forget it. The statue stands therein Piazza della Minerva on a classical plinth swishing its preternaturally long, trunk. On the elephant’s back is a tall and presumably very heavy obelisk, hence the rather weary expression on the elephant’s face.

The statue was unveiled in 1667. The elephant itself was probably executed by Bernini’s assistant Ercole Ferrata while that the Egyptian obelisk itself was probably uncovered during excavations for the building of the church of Santa Maria sopra Minerva.

We know that Pope Alexander VII had been wanting for some time to do something monumental with the obelisk. Various preparatory drawings have been uncovered. One idea under consideration seems to be the figure of Father Time holding a scythe in one hand the obelisk in the other. Another proposal showed Hercules and various other allegorical figures supporting the obelisk. But Bernini’s idea - which looks to me very like an elephant waiting in the piazza while the owner of this obelisk delivery service finds out where his load is to be deposited – won out.

If the glamour of the roof terrace and the décor of the Stendhal Suite are not reasons enough to stay at Grand Hôtel de La Minerve then the fact that you open your shutters to gaze out on to Bernini’s bizarre obelisk-transporting elephant certainly is.