Bond of Brothers — the First Asian Hotel Chain

( words)

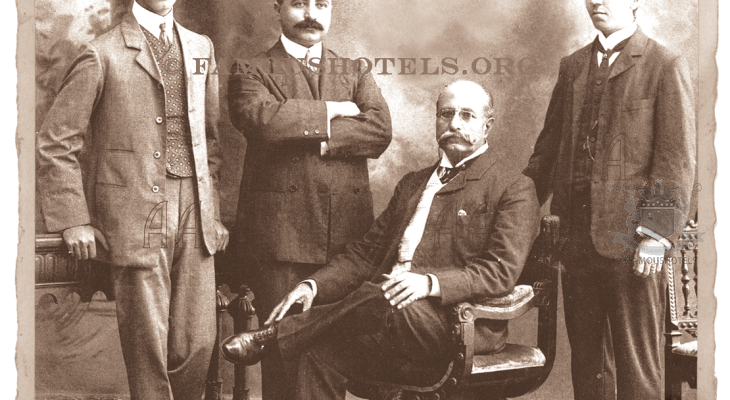

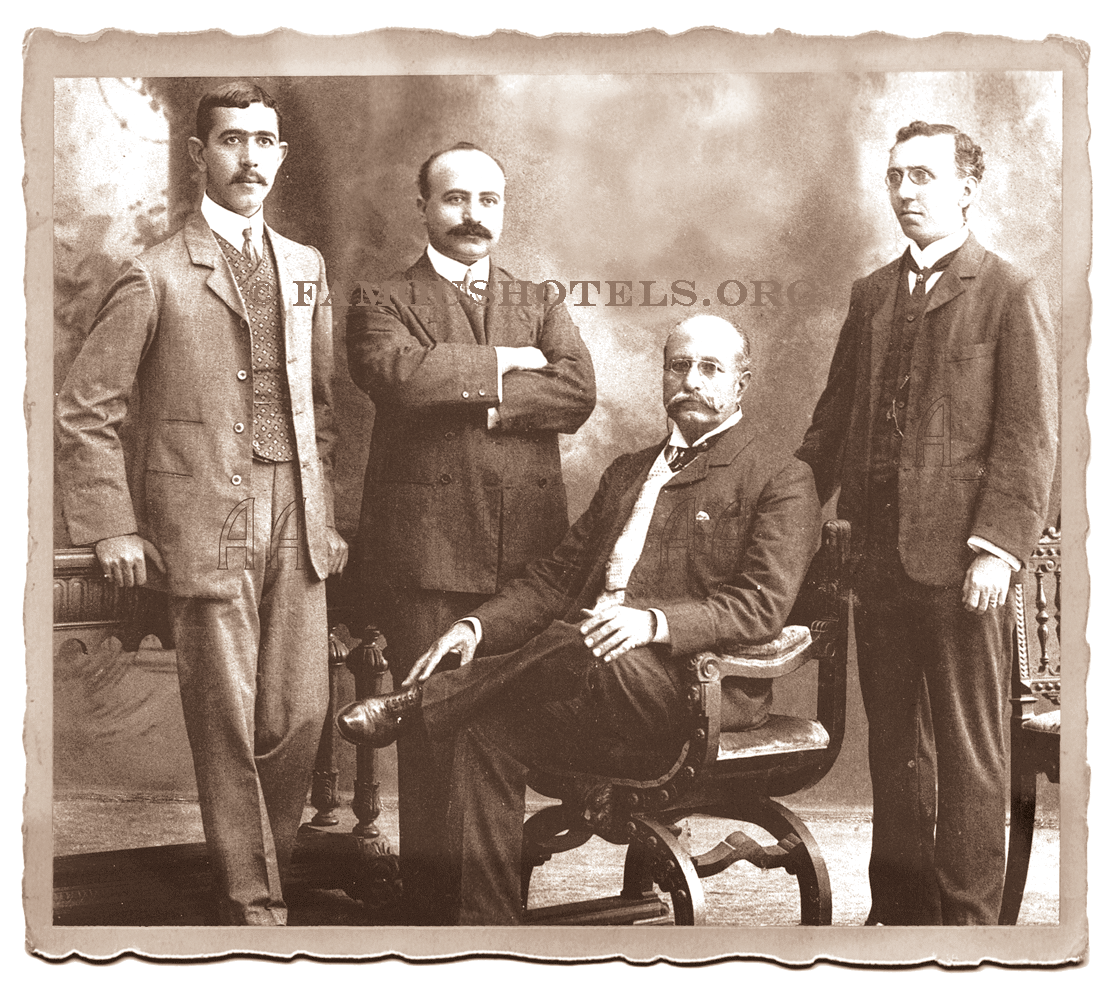

Martin Sarkies (seated) is surrounded by the young generation of successful hotelkeepers. Joe Constantine (left), his brother Arshak and Martyrose Arathoon, a Sarkies partner..

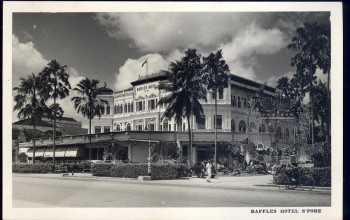

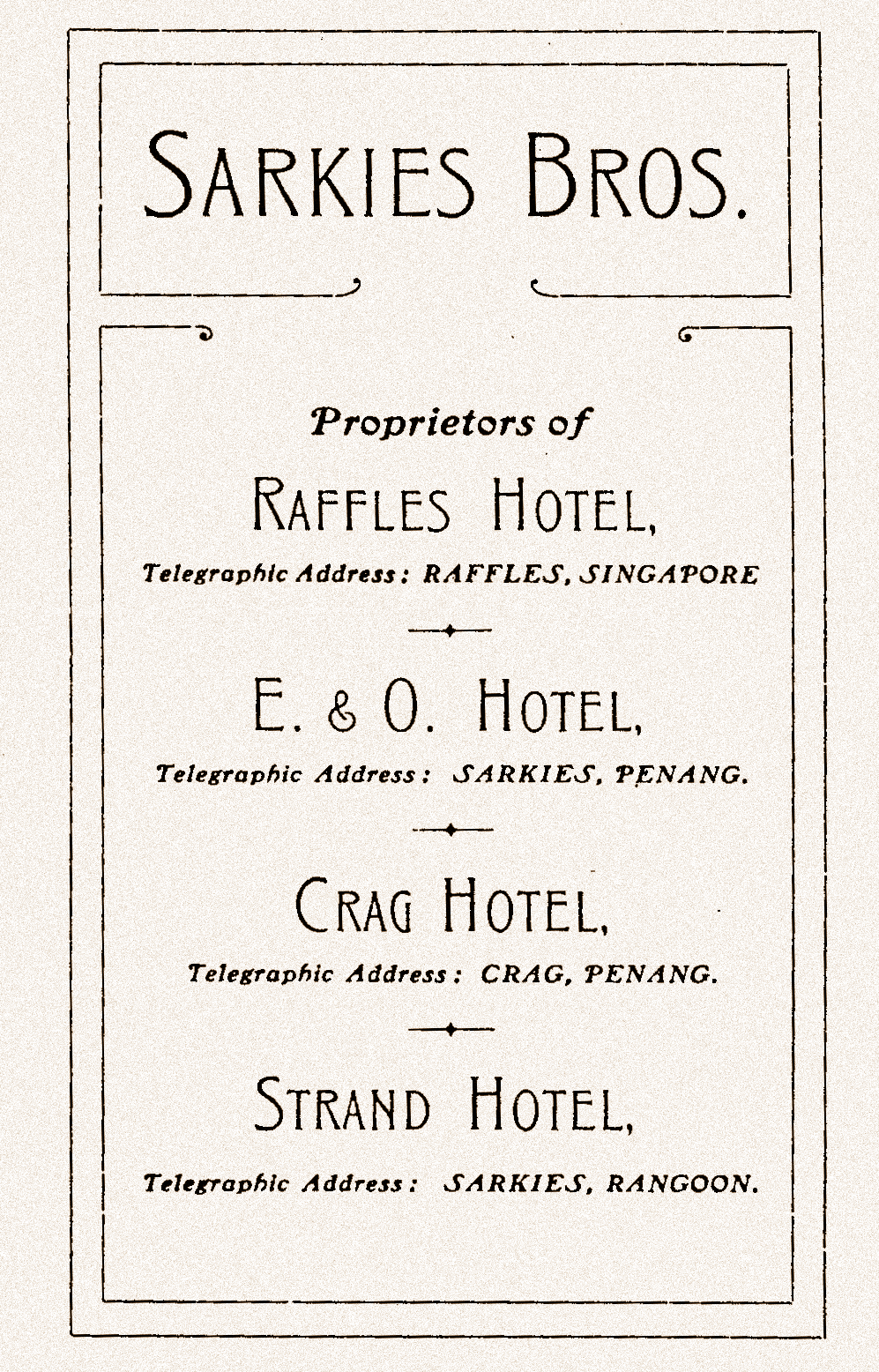

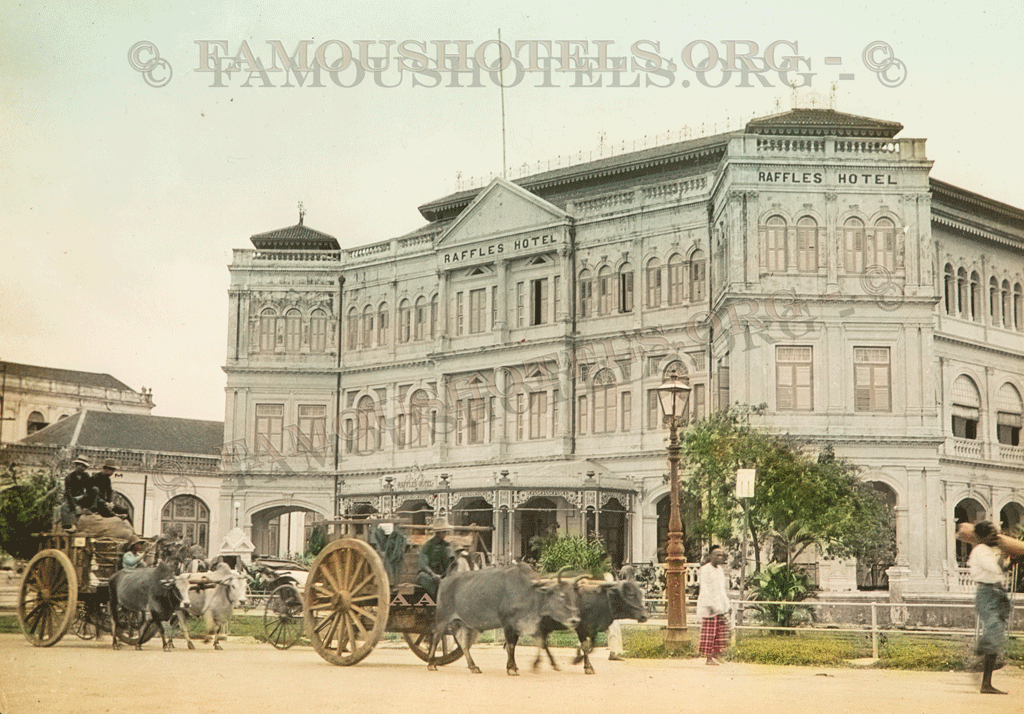

The Sarkies brothers - Martin, Tigran, Aviet and Arshak who came from Isfahan in Persia, became the foremost hoteliers of the East, their enterprises in Penang and Singapore dominating the hospitality trade in the Straits Settlements for nearly fifty years. With Raffles Hotel in Singapore, they had a remarkable flagship. Today, Raffles Hotel has been transformed into a global chain of luxurious caravanserais.

In the 1880s the Sarkies developed a new mixture of Asian-European hospitality hitherto unknown in Southeast Asia. Their background as traders and merchants, coupled with their lack of experience in international hospitality, helped them to develop a new view of the actual needs of potential guests, unhampered by prevailing notions. With Persian connections, they brought caviar from the Caspian Sea to Penang, Singapore and Rangoon. For almost five decades, they built, opened and ran hotels which have become legends in their own right.

The Sarkies had learned that the seashore was the best location. Inland – they instinctively felt – was dead land. Long ago, their ancestors had been traders in Isfahan in the highlands of ancient Persia, far away from the sea. For centuries they had benefited from the prosperous trade between Europe and the new colonies of India, the Malayan peninsula and the archipelago of Indonesia, on the main trade and transport route. Around 1820, they experienced the decline of this ancient trading route, known to us as the Silk Road. At some point there was no longer any need for caravans and their goods to cross the deserts, to climb the mountains and to follow the routes that Marco Polo had described. By 1869, with the opening of the Suez Canal, there was no longer any need to go through Isfahan. One day, the godowns surrounding the marketplace of Isfahan were empty. Once, they had been filled with tea from the highlands of Ceylon, sugar from Java, and opium, silk and porcelain from China and India. But now, even the local merchants who wanted to export their Shiraz wine had to take it to Ormus, at the shores of the Persian Gulf.

On the waterway between the shores of Asia and Europe, they met the swift sailing ships of the various East India companies. ‘Modern times’, they realized, and it became irrevocably clear that the day had come when the flourishing trade they had once plied in Isfahan was about to dry up like a pond in the desert. At that point, the clever Armenians of the desert cities of Persia, permanently pressed between the political interests of the Osman and the Russian Empires, packed their bags. As trade follows the flag they moved to the new and prospering ports of India and Asia.

Martin Sarkies (seated) is surrounded by the young generation of successful hotelkeepers. Joe Constantine (left), his brother Arshak and Martyrose Arathoon, a Sarkies partner.

The Sarkies family belonged to the first wave of Armenian economical refugees, paving the way for many to follow in this historically significant Diaspora. There is a saying about the famous Kadoorie family in Hong Kong; "they arrived on camels and left in Royce Royce".

However, the Sarkies had arrived to stay.

A certain Johannes Sarkies became an eminent merchant in Calcutta in the early 19th century. When Stamford Raffles founded – and soon after developed – Singapore in the 1820s, other members of the Sarkies family boarded one of the first sailing ships bound for the new trading place at the tip of the Malayan peninsula. Soon, two thirds of all Armenian trading houses in Singapore were owned by Aristarchus and Aratoon Sarkies. Another Sarkies, C Johannes Shahnazar, moved to Batavia (known to us as Jakarta) and founded Sarkies, Edgar & Co. of Batavia, Sourabaya and Singapore (1855-85). Another Sarkies branch settled in Dacca, while in 1869 a certain Martin Sarkies, an engineer, put down roots in Penang. He and his brothers Arshak, Aviet and Tigran, who arrived years later, were to become ‘our’ Sarkies, the farsighted hotel entrepreneurs.

Penang was an important port of call. Together with the city state of Malacca and Singapore, it formed the Straits Settlements. The island (with its capital, Georgetown) was the first English settlement east of Calcutta, founded by Sir Francis Light in 1786. Light had cannons of silver coins fired into the jungles to motivate his Indian coolies to clear the wood to build a capital: Georgetown. Its city hall, the high court, a respectable collection of public buildings and private villas appeared very European (with the notable exception that the city was planned on the drawing board, following a simple grid system, in comparison to the old, organically grown medieval European cities).

The Chinese who arrived from Mainland China became ‘Straits Chinese’ and built rows of narrow family houses-cum- shops creating one of the famous ‘Chinatowns’ of Southeast Asia.

In 1869, when Martin Sarkies arrived in Penang, the Suez Canal was about to be opened. This was the most important event since Vasco da Gama first discovered the sea route from Europe to India in 1498. Suddenly, a city like Bombay in India was only 6,274 miles from London instead of 11,200 round the Cape. Soon, the journey from Europe to these Asian ports could be completed in half the time. With steam ships, the journey was even faster. Eighty percent of sea-going traffic was British. Taken together, these factors produced a matrix for more efficient Southeast Asia trade, and went on to become the grandmother of Asian tourism. Everybody in the region understood that, sooner or later, all ports East of Suez would be buzzing like beehives.

However, there was a distinct lack of good accommodation for travellers arriving after an exhausting voyage. After days and weeks in narrow, uncomfortable cabins (moving on the deck during the night to avoid the unbearable heat of the tropics), they often had to rent an equally uncomfortable and overpriced room, if indeed, there were any to be had.

Hoteliers felt that their duty was done if they offered a room away from the dirt and dust of the street, away from rats and straying dogs, beggars and thieves. But that was it. Asia had little to offer compared to the luxurious, dreamlike palaces created in Europe by the first apostles of hospitality such as Cesar Ritz. In Europe, monograms were embroidered onto bed linen, pillows and towels, and delicate porcelain figurines were placed on mantelpieces. Asian guesthouses rarely offered sheets at all, and a mosquito net was often the only luxury. In 1889, for example The Savoy in London already offered 70 bathrooms with tubs and running hot and cold water. At this time, Asian hoteliers were proud of their ‘showers’, which consisted of a wooden ladle which was used to pour water onto the bather from a large clay receptacle (a ‘Tong’). Doors were rarely lockable and servants would enter through back doors at their convenience. Requests were understood once in a blue moon and items wrongly delivered, organized and served for that funny traveller who requested ‘my own knees’ to put on his salad.

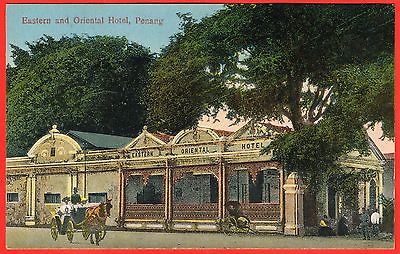

Penang - The Eastern and Oriental (E&O):

Penang was no exception in terms of accomodation, and therefore the perfect location for a high(er) quality hotel.It started in Penang: it was 23-year-old Tigran who took the first step into the hotel industry, seeing it as more profitable than his fledgling auctioneering business. Taking over the lease of a large compound house at 1a Light Street, he named it the Eastern Hotel, announcing on 15 April 1884 that the hotel was open to receive boarders. Tigran was joined by his older brother Martin, and calling themselves Sarkies Brothers, the pair acquired Hotel de l’Europe which was situated on the seafront in Farquar Street, and renamed it the Oriental Hotel. Tigran managed the Oriental while Martin was responsible for the Eastern. Younger brother Aviet was persuaded to join them and was soon made manager of the Eastern Hotel. By August 1889, the extended and entirely renovated Oriental Hotel was ready for the public. The brothers gave up the Eastern, but not wanting to lose the goodwill and familiarity of its name, decided to rename the Oriental, the Eastern and Oriental Hotel - which soon became shortened to the E. & O.

The E&O hotel was a success. Perhaps a bit too much of a success. The landlord realised how much the value of his properties had risen, and he increased the rent considerably. The Sarkies began to look around for more reasonable opportunities.

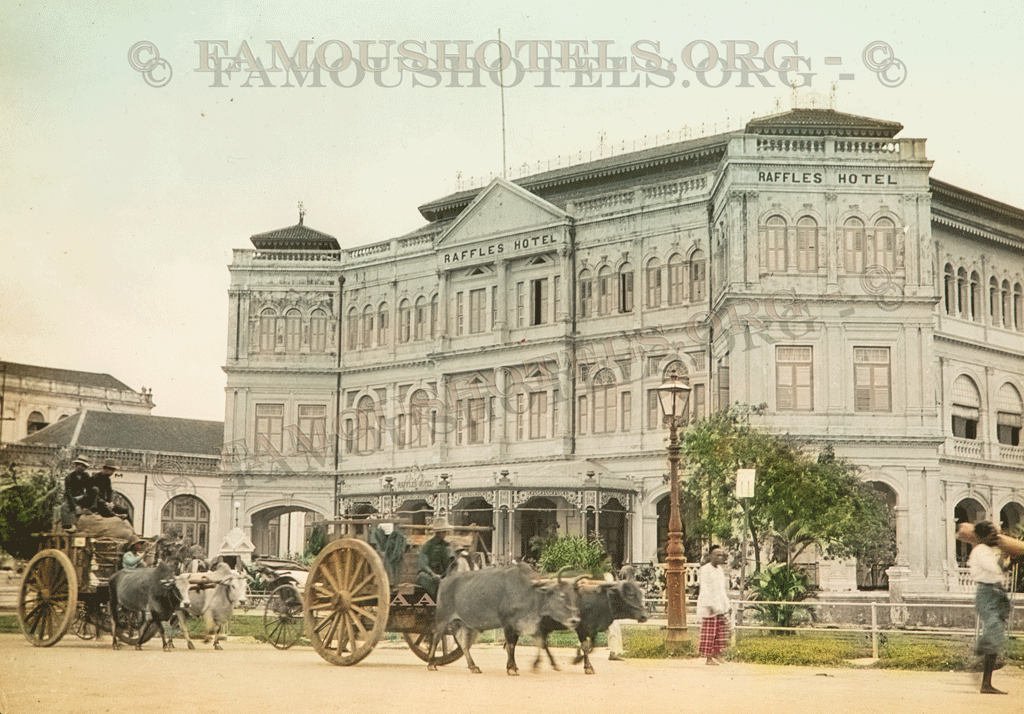

In 1887, the Sarkies went scouting for a good location to establish a hotel in Singapore. They found Beach House, a former boys’ boarding house, at ‘20 House Street’. The Chinese name of the street dated back to Singapore’s early years, when Sir Stamford Raffles had drawn up the layout for this new city. Now this street, facing the shoreline of Singapore, has been renamed Beach Road.

The Sarkies’ keen sense for location led them to come to an agreement with the owner, an Arab merchant, called Syed Mohamed Bin Ahmed Al Sagoff, and they rented the house. Here, on 1 December 1887, they opened Raffles Hotel, a small hostelry with ten bedrooms.

In the meantime, the landlord at Penang possessed enough good sense not to let the Sarkies leave. Their talent as hoteliers was too obvious. An acceptable agreement was made and suddenly the Sarkies were in possession of two hotels. One in Singapore and one in Penang. When Martin retired to Isfahan in late 1890, youngest brother Arshak joined the E. & O., having gained valuable work experience at Raffles under Tigran’s watchful eye. Soon each brother took responsibility for a different hotel. Tigran remained in charge of Raffles, while Aviet opened the Sarkies Hotel in Rangoon, leaving Arshak in control of the E. & O. Apart from short breaks in Singapore or abroad, Arshak ran the hotel until his death in 1931. Within a decade of opening the Eastern Hotel, the brothers’ reputation had been made.

Orang Sarkies

Speaking at a celebratory lunch at the E. & O. in 1893, Sir Frank Swettenham first told the joke which was to pass into history: ‘A little boy was asked by his teacher in Perak who the "Orang" Sakais were, and replied that they were people who kept hotels.’ (The "Sakais" are one of the indigenous races of Malaysia, and now the Oragn Sarkies were the race of hotelkeepers!)

It was time to expand, again. Now they turned to the North. To Rangoon, the prospering city on the Irrawaddy River. A city with so many opportunities. A city with no proper hotel. After 1886, when Upper Burma was annexed by the British desire for extended safe trading facilities and united with the lower part of the country, Burma was declared part of British India and Rangoon was its capital. After the visit, also in 1886, of the Viceroy, Marquis of Dufferein, the city was on its way to becoming one of the cornerstones of the British Empire. In 1892, Aviet (the youngest of the brothers) and Tigran Sarkies boarded a steamer bound for Rangoon. Tigran had been instrumental in setting up Raffles Hotel in Singapore. He had built the billiard room and he had introduced fine cuisine to Singapore. He had brought the first caviar to the colony.

The story of The Strand Hotel, Yanon:

Singapore - Raffles:

With experience gained from running their hotels in Penang, Tigran and Martin Sarkies investigated the possibility of opening a new hotel in Singapore. They found a large bungalow on the corner of Beach and Bras Basah Roads, fronting the seashore, yet quite close to the commercial centre of town. Previously the boarding house for boys at the nearby Raffles Institution, the bungalow needed only a few alterations and repairs before Tigran announced the opening of his new hotel which he called Raffles, in December 1887. His initial advertisement highlighted the factors that would make Raffles such a success: the promise of ‘great care and attention to the comfort of boarders and visitors’. Hotel extensions in 1889 soon proved insufficient, so the brothers opened a new two-storey Palm Court Wing in December 1894, offering thirty well-furnished suites, bringing the hotel’s total to seventy-five.

Sarkies Brothers were rewarded for their efforts as members of royal and aristocratic families and other dignitaries began to patronise Raffles. But the Straits Times remained scathing of Singapore’s hotels, declaring that Singapore lacked a well-designed, convenient hotel offering quality accommodation. Presumably Tigran heeded this criticism for he announced extensive, grandiose renovations in 1897. These plans finally won over the Straits Times which concluded that the ‘palatial building with excellent ventilation, and the vast airy dining room’ would make Raffles ‘one of the largest and handsomest hotels in the East’.

The new wing was opened on 18 November 1899. The old central block had been replaced by a magnificent Renaissance style three-storey block featuring a huge T-shaped dining room as the centrepiece. Boasting a Carrara marble floor, it seated 500 and occupied the whole of the ground floor, while its roof, crowned by a skylight gave the room an awesome air space. The two upper floors each contained fifteen suites, plus a large reading room and two drawing rooms. Two suites were set aside for Tigran and his family. A wide, richly decorated verandah surrounded the building, protecting the rooms from sunlight and rain while the new billiard room and bar were sensibly housed in a separate block. The hotel now offered 100 suites, all with furniture suited to the climate, as well as electric lighting - making Raffles the only hotel in the Straits lit by electricity. Not only did the hotel have its own steam engine to generate electricity, but a 10,000-gallon tank ensured a steady water supply. A special inauguration dinner for 200 guests was held in the dining room where electric light was used for the first time. The Straits Times representative who went along after the grand opening to see what things were like on an ordinary night, was most impressed, especially by the blazing lights as he approached the hotel from the sea front. Indeed, his only complaint was that the drawing rooms were unsuitable for flirting - due to a lack of screens, anyone who walked along the passageways could look in. Tigran should have sought the advice of a lady, he admonished. Tigran was quick to respond, assuring the writer that when the drawing rooms were finished, they would give every facility for flirtation. Ecstatic reviews of dinners dotted the press for the next three decades. Among early successes was the 1900 New Year’s Eve dinner. Lauded as the best banquet yet offered by a hotel in Singapore, it was claimed that half the town turned up for the dinner and the rest came in later to dance. However, travellers were once more complaining of the dearth of quality accommodation, strongly feeling that a first rate hotel under European management was urgently needed. Perhaps such comments en¬couraged Arathoon Sarkies and Eleazar Johannes to acquire the Adelphi Hotel in 1903, and the new owners of the Hotel de l’Europe to construct a modern hotel in 1904 (poaching Charlie Chaytor from Raffles to manage it). These entrepreneurial Armenians in charge of Singapore’s three leading hotels kept one another on their toes. An intense advertising war ensued as each tried to outdo the other vying for patronage for their special dinners, race dinners, coronation dinners and musical dinners. They wooed the diverse expatriate communities with lavish menus accompanied by musical delights to celebrate the birthdays of Kaiser Wilhelm, Queen Wilhelmina, King Edward and Queen Alexandra. In November 1910, having guided Raffles for twenty-three years, a sick Tigran sailed for England. Of some consolation would have been the Pinang Gazette’s glowing praise of his achievement - 'Raffles is more than a hostelry, it is an institution – the hotel has made Singapore famous to the tourist and an abode of pleasure to the resident.'

The new wing was opened on 18 November 1899. The old central block had been replaced by a magnificent Renaissance style three-storey block featuring a huge T-shaped dining room as the centrepiece. Boasting a Carrara marble floor, it seated 500 and occupied the whole of the ground floor, while its roof, crowned by a skylight gave the room an awesome air space. The two upper floors each contained fifteen suites, plus a large reading room and two drawing rooms. Two suites were set aside for Tigran and his family. A wide, richly decorated verandah surrounded the building, protecting the rooms from sunlight and rain while the new billiard room and bar were sensibly housed in a separate block. The hotel now offered 100 suites, all with furniture suited to the climate, as well as electric lighting - making Raffles the only hotel in the Straits lit by electricity. Not only did the hotel have its own steam engine to generate electricity, but a 10,000-gallon tank ensured a steady water supply. A special inauguration dinner for 200 guests was held in the dining room where electric light was used for the first time. The Straits Times representative who went along after the grand opening to see what things were like on an ordinary night, was most impressed, especially by the blazing lights as he approached the hotel from the sea front. Indeed, his only complaint was that the drawing rooms were unsuitable for flirting - due to a lack of screens, anyone who walked along the passageways could look in. Tigran should have sought the advice of a lady, he admonished. Tigran was quick to respond, assuring the writer that when the drawing rooms were finished, they would give every facility for flirtation. Ecstatic reviews of dinners dotted the press for the next three decades. Among early successes was the 1900 New Year’s Eve dinner. Lauded as the best banquet yet offered by a hotel in Singapore, it was claimed that half the town turned up for the dinner and the rest came in later to dance. However, travellers were once more complaining of the dearth of quality accommodation, strongly feeling that a first rate hotel under European management was urgently needed. Perhaps such comments en¬couraged Arathoon Sarkies and Eleazar Johannes to acquire the Adelphi Hotel in 1903, and the new owners of the Hotel de l’Europe to construct a modern hotel in 1904 (poaching Charlie Chaytor from Raffles to manage it). These entrepreneurial Armenians in charge of Singapore’s three leading hotels kept one another on their toes. An intense advertising war ensued as each tried to outdo the other vying for patronage for their special dinners, race dinners, coronation dinners and musical dinners. They wooed the diverse expatriate communities with lavish menus accompanied by musical delights to celebrate the birthdays of Kaiser Wilhelm, Queen Wilhelmina, King Edward and Queen Alexandra. In November 1910, having guided Raffles for twenty-three years, a sick Tigran sailed for England. Of some consolation would have been the Pinang Gazette’s glowing praise of his achievement - 'Raffles is more than a hostelry, it is an institution – the hotel has made Singapore famous to the tourist and an abode of pleasure to the resident.'

Arshak managed Sarkies Hotels until his end. Tigran and Martin had died in 1912, Aviet in 1923. On 9 January 1931 Arshak died at his beloved E&O Hotel. On 10 June 1931, the same year, Singapore businessman Tang Men Jim filed a bankruptcy case against Raffles Hotel for Straits Dollars 35,236.87 worth of food supplies. The case grew into the largest bankruptcy affair of the Straits Settlements. The firm of Sarkies Brothers, hotel proprietors, had total liabilities of 3.5 million owing to 195 creditors. Arshaks family had to leave their suite at the E&O hotel, a Raffles Hotel Ltd was put in charge, and the story of Messrs Sarkies Brothers, pioneers in their line of business, had come to an end. The story of the hotels involved, gladly, not. Raffles Singapore, the E&O in Penang and the Strand have all survived under different owners. The Crag on Penang Hill does not exist any longer.

Explanations:

The Sarkies

Martin Sarkies (1852-1912)

Tigran Sarkies (1861-1912)

Aviet Sarkies (1862-1923)

Arshak Sarkies (1868-1931)

: The Armenian genocide of the people living in Eastern Turkish provinces was the first genocide of the 20th century, perpetrated by the Ottoman Turkish government against its defenceless and law-abiding citizens, the Armenians, a Christian minority in a Muslim state. For more than a quarter of a century, the Armenians in the Ottoman Empire under the leadership of Sultan Abdul Hamid II and later under the rule of the Young Turk regime suffered unspeakable abuse, torture, massacres and persecution. This resulted in the rape, murder and deportation of more than 1.5 million Armenians from their historic homeland, and the destruction of a 3000-year-old heritage and rich culture.

: Martin Sarkies had five children. His son Lucas Martin, born in 1876 in Penang, later founded the famous hotel Oranje. He moved to Malang and later to Surabaya, where he opened a grocery store. When a large piece of land became available he bought it and in 1910, his little son Eugene Lucas Sarkies had the honour of laying the groundstone for the Oranje Hotel, named for the Dutch royal family. Today the hotel is called Hotel Majapahit of Surabaya in East Java.

: The Sarkies also run and operated the Crag Hotel on Penang Hill, the cool retreat from the heat of the plains. And the Seaview Hotel in Singapore.

Sources:

Ilsa Sharp: 'There is only one Raffles';

Nadia H Wright: 'Respected Citizens: the History of Armenians in Singapore and Malaysia'

Andreas Augustin: 'The Strand, Yangon', 'The Raffles Treasury', 'Raffles Singapore';

Andreas Augustin: set of original architecture drawings Raffles Hotel (1897-1899), unearthed in 1987.