The Randolph — A Perspective of Oxford

( words)

Teaching exists at Oxford since 1096 and developed accordingly from 1167, when King Henry II banned English students from attending the University in Paris. As the oldest university in the English-speaking world, Oxford is a unique and historic institution. Its most famous hotel is comparatively young. The Randolph opened in 1866. It very quickly established itself as what it was always intended to be: a suitable place for both visiting dignitaries and parents to stay when in Oxford.

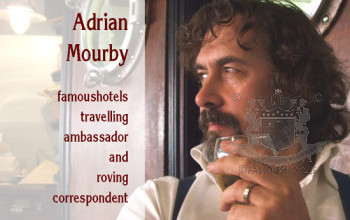

The Randolph — A Perspective of Oxford

By Adrian Mourby

As someone who spent the first night of his honeymoon at The Randolph in 2004 I soon decided that if Thomas Mann had chosen instead to write Death in Oxford, this hotel would be where Gustav von Aschenbach met his beautiful young man among the aspidistras, string quartets and potted palms. The hotel, known in the early 21st century as the Macdonald Randolph always had an air of being slightly underfunded but history abounded in every nook and cranny.

In 2015 The Randolph made headline news across Britain. Disaster had struck when a fire began in the kitchens as beef stroganoff was being prepared. Flames leapt up within the chimney stack and set alight the hotel's vertiginous mansard roofing. The city centre ground to a halt as every available fire engine tackled the blaze. Town and Gown alike were shocked when The Randolph closed for the first time in its 129 year-old history. The hotel, such an architecturally controversial structure when it opened in 1886 had become so much a part of Oxford that its loss was almost as unthinkable as the destruction of the Ashmolean Museum or the Sheldonian Theatre.

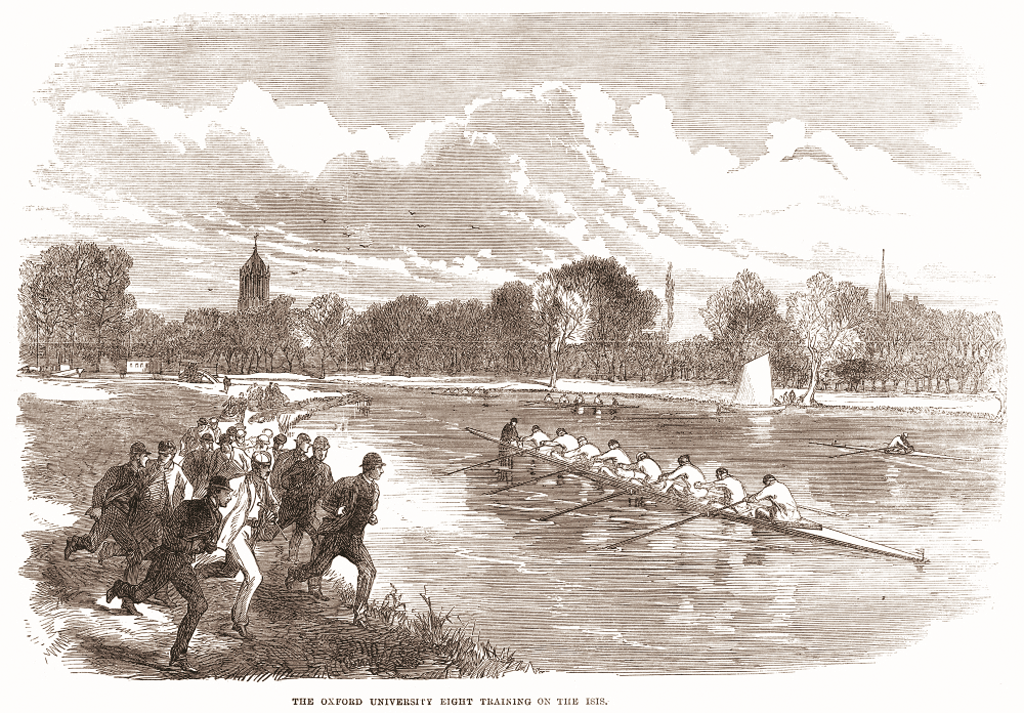

Boat Race 1866 — the Oxford University Eight Team

Big changes were coming to the Randolph however. Sadly, in 2017, Michael Grange died at the relatively young age of 61. A number of aspiring but short-lived general managers took over from him until Philip King arrived in July 2019. Soon afterwards the Macdonald Group relinquished its showcase hotel and sold it to A.J.Capital & Partners whose CEO, Ben Weprin runs Graduate Hotels, a collection of “handcrafted” hotels in university communities across the U.S. and U.K. For an entrepreneur Weprin has very distinct vision about décor. On his first tour of the hotel with Macdonald's new GM, Philip Lewis he was clearly struck by its potential. “I had no idea who he was,” said Philip Lewis. “He was wearing a baseball cap and he seemed to like everything he saw and at the end of our walk round he said “Yes I think I’ll buy it”.

Around 1910: Group of four women at a tea party within the grounds of Somerville College Oxford. Photograph by Henry W Taunt. Copyright © Oxford University Images /

Weprin has been very hands-on in the refurbishment of the Randolph. “He came and looked at the new Alice restaurant,” says Philip Lewis. “And he said he liked the wallpaper but he wanted it on the ceiling as well. Which was a shame because we’d just taken down the scaffolding!”

Graduate Hotels, who already owned a UK property in Cambridge endeared itself greatly to the townspeople of Oxford by flying its black and white Graduate flag over hotel’s entrance while reverting to the original name. The Randolph – pure and simple – is the only one of Graduate’s 32 hotels worldwide to be known by its local name rather than being The Graduate, Oxford.

The hotel’s multi-million pound refurbishment coincided with England’s many Covid lockdowns following March 2020 and the official reopening only occurred in January 2022.

“You might say we got lucky,” says Phil Lewis who has now been GM under both Macdonald and Graduate Hotels. “We only ever had enough rooms available as the market demanded. Next month (February 2022) I get my last 40 bedrooms back just as demand is increasing. Wedding bookings in 2022 are twice what they were pre-pandemic.”

The official reopening of the hotel – long delayed from a covidious November 2021in Britain - took place on Friday 21 January at the best party that Oxford has seen for almost two years – if not several decades

“It was amazing,” says Philip. “At these events it’s usual for 40% of people to cancel at the last minute. But we had 100% attendance from those who had said yes.”

As one who attended, I can attest that this was a party that brought glamour back to Oxford after 22 desolate months of successive government lockdowns. Maybe this was what it was like to step out of the austerity of the First World War (when the Randolph served as a hospital for recovering British soldiers) directly into the Roaring Twenties.

For all that the Randolph is now an Oxford institution it originally sat very uneasily in this city. There was always something audacious about its tall, mansard roofline whose very height dominated the surrounding colleges.

The Randolph has had a dramatic history over the past 136 years, turning from Oxford’s most unpopular building to one of its most beloved.

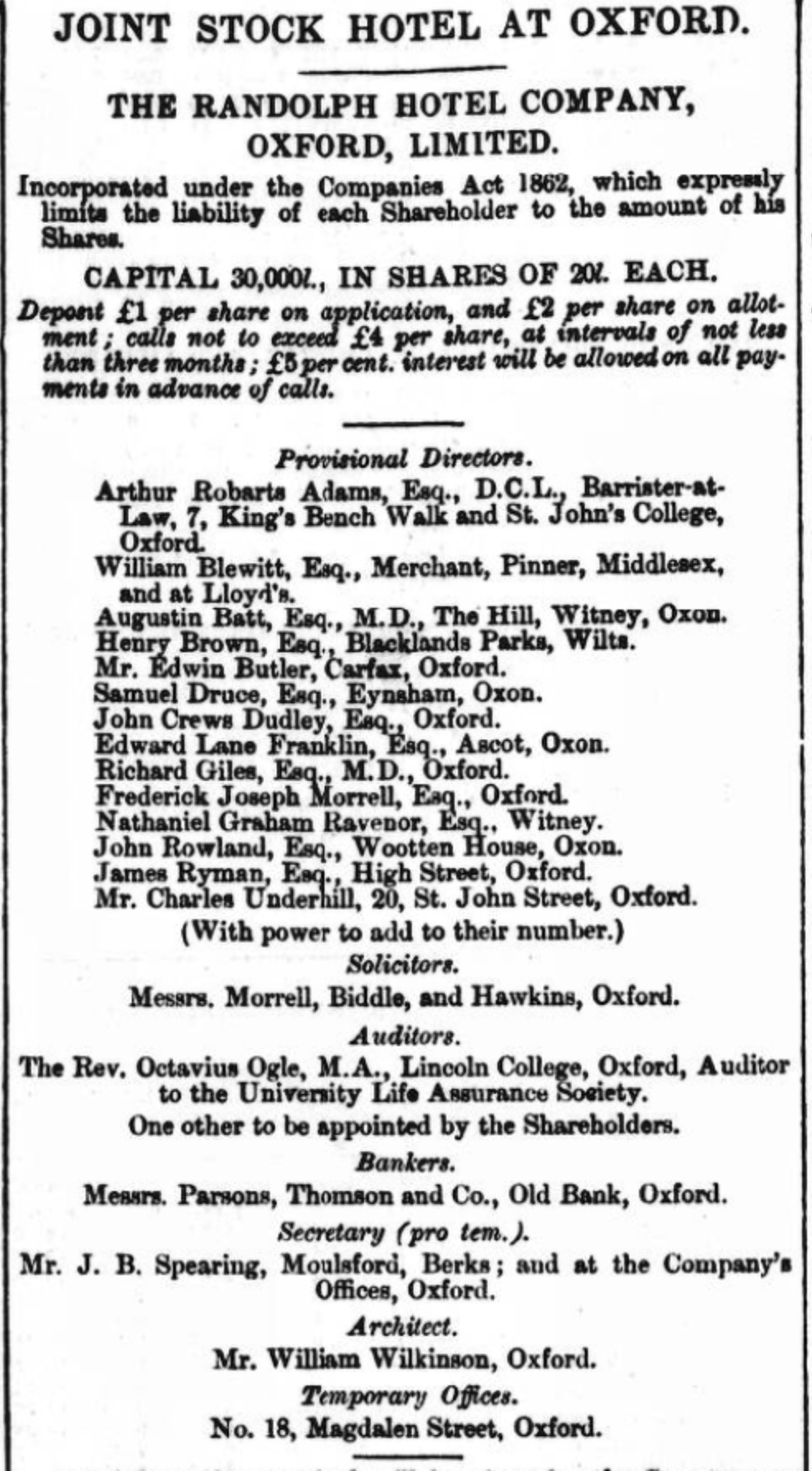

The first list of directors of the Joint Stock Randolph Hotel Company in 1863 (click image to enlarge).

The first list of directors of the Joint Stock Randolph Hotel Company in 1863 (click image to enlarge).

Many visitors believe it was named after Randolph Churchill, the father of Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Lord Randolph, second son of the Duke of Marlborough, obtained a decent degree at Merton College Oxford. His own second son Winston was born at nearby Blenheim Palace during a ball. But it was not Lord Randolph who lent his name to the neo-Gothic hotel on the corner of Beaumont Street. In fact Randolph Churchill was said to have smashed the windows of the hotel while an uproarious, over-entitled undergraduate.

Actually the hotel takes its name from Dr Francis Randolph, a University benefactor who had been Principal of St Alban Hall (now part of Lord Randolph’s Merton College), and who died in 1796 leaving a lot of money to the University. The art gallery he funded became part of the Ashmolean Museum’s collection. Why exactly Oxford’s premiere hotel was named after the (currently) obscure Dr Randolph needs further investigation.

The reason for the initial unpopularity of the hotel that bears Dr Randolph’s name was down to its design at a controversial time in Britain’s architectural history. The Gothic Revival was taking root in academic cities like Oxford where University men were rejecting neo-classicism and wanted something more visceral - and North European. In 1863 everyone agreed that Oxford needed a superior commercial hotel, especially because the newly married Prince and Princess of Wales would surely be visiting soon and the city lacked accommodation for a royal entourage. Absolutely no-one wanted Prince Albert and Princess Alexandra to be boarding at Blenheim Palace.

So plans were drawn up by local architect William Wilkinson to erect a Gothic structure on a corner of land opposite the neo-Classical Ashmolean. (Lovers of England’s blue plaques will notice that Wilkinson’s own house is situated directly opposite the Ashmolean and right next to the Randolph in Beaumont Street).

The opening report takes up two columns of the Oxford Journal

While the architect received support from men like the great art critic John Ruskin who was keen promote Protestant Neo-Gothic architecture in Britain, his designs were condemned by many who saw this hotel as despoiling the classical lines of Beaumont Street, the “finest ensemble of gentlemen’s houses” in the city. Wilkinson’s new hotel was considered too big and too tall in the way that it towered over its surroundings. And its style was in complete contrast to the rest of the nearby buildings, a semi crescent of neoclassical townhouses that wouldn’t have looked out of place in the city of Bath.

Moreover for some people the Randolph was an insult to the museum that stood immediately opposite it: the Ashmolean was and is, perhaps the most perfect neo-classical building in Oxford. It had been completed in 1845 but in the intervening 20 years English architecture had gone off in all sorts of directions.

The Italianate perfection of the "Ashmo" was now confronted by something that resembled a French chateau, redesigned in yellow brick with a proliferation of spires, bay windows and Draculean pinnacles. While the Ashmolean hid its roof behind a parapet, the Randolph was pretty much entirely slate roof. There were many protests about the design but eventually business considerations won out and a toned down neo-Gothic Randolph (minus its central spire) was built and duly opened for business in 1866.

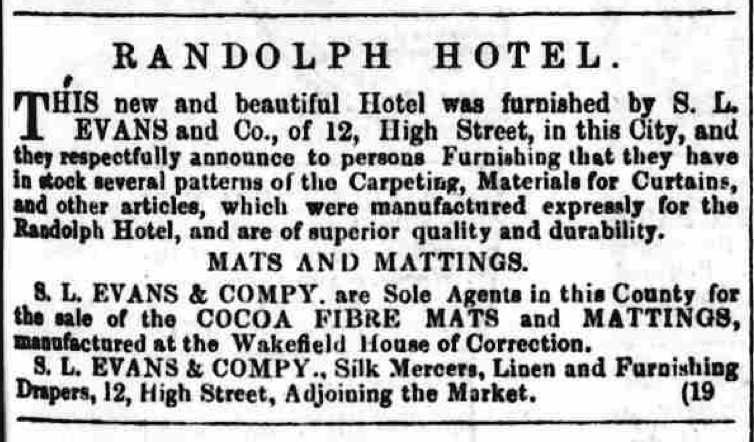

Testimonial "Randolph"

Post royal visit, this hotel very quickly established itself as what it was always intended to be, suitable place for both visiting dignitaries and wealthy parents to stay when in Oxford.

John Betjeman, an Oxford student and future 20th Century Poet Laureate summed up the contrasting sides of Beaumont Street very well: “This tall, vertical Victorian hotel was a Gothic answer to the Classic composition of the Ashmolean and Taylorian buildings on the other side of the road. Both buildings, despite their difference in style, were satisfactory upright terminations to the long low Georgian curve of Beaumont Street”

In 1894 the hotel proudly added an “American Elevator” and a ballroom in 1899 and, finally an extension down Beaumont Street in 1923 which the city fathers had hoped would be a little more Georgian in style but in the end the Randolph Hotel Company once again got its own way and the neo-Gothic line was extended with lots of medieval windows – and absolutely no apology.

By the beginning of the twentieth century guests could enjoy a Billiard Room, a Ladies’ Coffee Room and "a conservatory for smoking”. The hotel also advertised that it stocked “Fine Wines Imported From Abroad”. And it had good stabling (behind William Wilkinson’s house) which in due course became its garage.

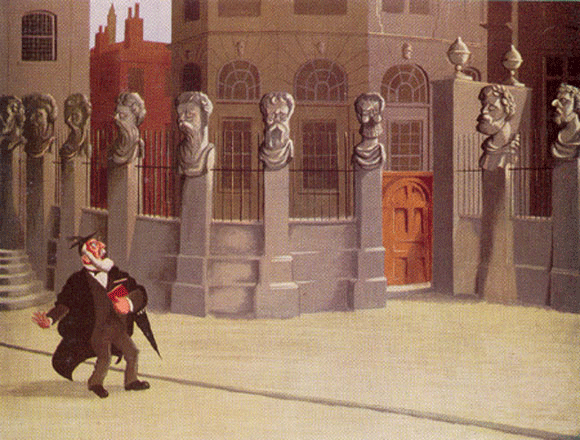

From one of twelve paintings in the Randolph Hotel, Oxford by Osbert Lancaster, illustrating Sir Max Beerbohm’s novel Zuleika Dobson (reproduced with kind permission of the Randolph Hotel). The official name for such heads is “herms”; the original accounts describe these heads as “termains”; and some people call them philosophers. But Max Beerbohm in Zuleika Dobson called them “Emperors”, and that is the name that has stuck. Each head shows a different type of beard. In that novel, Beerbohm wrote: ”Here in Oxford, exposed eternally and inexorably to wind and frost, to the four winds that lash them and the rains that wear them away, they are expiating, in effigy, the abominations of their pride and cruelty and lust. Who were lechers, they are without bodies; who were tyrants, they are crowned never but with crowns of snow; who made themselves even with the gods, they are by American visitors frequently mistaken for the Twelve Apostles.”

From one of twelve paintings in the Randolph Hotel, Oxford by Osbert Lancaster, illustrating Sir Max Beerbohm’s novel Zuleika Dobson (reproduced with kind permission of the Randolph Hotel). The official name for such heads is “herms”; the original accounts describe these heads as “termains”; and some people call them philosophers. But Max Beerbohm in Zuleika Dobson called them “Emperors”, and that is the name that has stuck. Each head shows a different type of beard. In that novel, Beerbohm wrote: ”Here in Oxford, exposed eternally and inexorably to wind and frost, to the four winds that lash them and the rains that wear them away, they are expiating, in effigy, the abominations of their pride and cruelty and lust. Who were lechers, they are without bodies; who were tyrants, they are crowned never but with crowns of snow; who made themselves even with the gods, they are by American visitors frequently mistaken for the Twelve Apostles.”

(Source: http://www.oxfordhistory.org.uk/broad/history/emperors.html)

Lancaster

Perhaps the guest to leave the greatest mark on the hotel was cartoonist, art critic and stage designer Sir Osbert Lancaster. His twelve illustrations to the novel Zuleika Dobson, An Oxford Romance were – and still are - hung in its drawing room (without a doubt the finest place for afternoon tea in Oxford). They were initially displayed in the new Art Deco ballroom in 1937. According to hotel legend the wealthy Sir Osbert paid for his stay at the Randolph with these witty depictions of Oxford life in the years before World War I. But that’s probably apocryphal. Lancaster was never short of money and he probably knew how much these original oil paintings would fetch if he sold them. Famous artists who have paid for their accommodation with works of art are a common myth in the hotel world, along with the ghost of a grey lady and the belief that the real Ernest Hemingway used to prop up the hotel bar. (Not a claim made in Oxford).

"The Snug"

When World War I broke out in 1914 the hotel was one of many across Britain that gave up its ballroom and drawing room for convalescent soldiers returning from fighting in France and Belgium. In the 1920s Evelyn Waugh, who mentioned the hotel in his novel Brideshead Revisited, once shocked diners at the Randolph by intervening in a discussion on bisexuality and declaring loudly “Buggers have babies”. Kingsley Amis’s future wife Hilly earned the novelist’s admiration by sneaking into the hotel to wash her hair and underwear while staying with him illicitly across the road at St John’s College (undergraduates were not officially allowed women guests in their rooms in the 1940s). Later Amis’ friend the poet Philip Larkin and the novelist Barbara Pym – who carried out a 14-year wholly epistolary relationship – finally met for lunch at the Randolph in 1975.

Morse

But for many people, in the last decades of the twentieth century the Randolph was most closely associated with two fictional characters, Inspector Morse and Sgt Lewis who featured in novels and dramatisations by local author Colin Dexter. In both books and in the TV series Inspector Morse the taciturn detective and Sgt Lewis regularly discuss their cases in the Randolph bar where Morse claimed, “They serve a decent pint”. In several stories, crime suspects dine or stay at the Randolph. And in the novel The Jewel that was Ours (dramatised as The Wolvercote Tongue) Morse investigates the suspicious death of an American hotel guest in her Randolph room.

In 2001 the bar where Colin Dexter had often sat as an extra in the TV series Inspector Morse was officially renamed The Morse Bar. This is the part of the hotel that has changed least during the recent refurbishment though it has been repainted a darker hue of green and given more atmospheric lighting. Sardonic photos of John Thaw (Morse) are everywhere on its oak-panelled walls.

In 2001 the bar where Colin Dexter had often sat as an extra in the TV series Inspector Morse was officially renamed The Morse Bar. This is the part of the hotel that has changed least during the recent refurbishment though it has been repainted a darker hue of green and given more atmospheric lighting. Sardonic photos of John Thaw (Morse) are everywhere on its oak-panelled walls.

The purchase of The Randolph by A.J.Capital/Graduate Hotels has brought a much needed injection of money into a great Oxford institution. A lot of work needed doing including getting rid of an ill-judged formica canopy over reception which spoiled the dramatic four-storey rise above to the hotel’s main staircase.

The new hotel – it is fair to call it a new hotel because it has been so thoroughly redesigned –has been dramatically rethought. Above reception 30 heraldic tabards hang down Wilkinson’s cantilevered stairwell. They are based on Oxford colleges – but with an element of artistic licence.

Blue-striped wallpaper is everywhere on the ground-floor. It is a light blue stripe, more reminiscent of Cambridge’s famous blue than Oxford’s but English Heritage has been quite firm with the hotel that a Victorian colour scheme has to be followed. More contemporary touches include a photograph of Oscar Wilde in every bedrooom. The former Oxford student who fell so dramatically from grace in 1895 is now warmly re-embraced for his wit and humanity.

Two dapper gentlemen at The Randolph: general manager Philip Lewis and famoushotels author Adrian Mourby

The Alice Dining Room is decorated with new faux-naif paintings of the Oxford Wonderland heroine by the artist, illustrator and printmaker, Amy Wiggin. Long gone are the heraldic shields of Oxford colleges, introduced at ceiling height by Macdonald hotels. These days guests sit on pink banquettes on a floor of white mosaic tiles. The Alice Bar, which leads off from the dining room has a low-ceilinged, dark snug where one could imagine whiling away an entire winter drinking whisky. And beyond it lies a lofty chef’s table where the breakfast buffet is laid out.

I recently met the general manager, Philip Lewis for breakfast and hotel tour. Philip joined in 2019 the Randolph while it was still part of Macdonald Hotels. He has since stayed on to oversee this multi-million pound refurbishment.

However much it has cost – and it’s a lot - he has never been told. “Never?” I repeat. And he remains diplomatically silent on the subject.

As ever, I put to him the famoushotels General Managers’ Breakfast questionnaire, lean back and listen.

Read: "Breakfast with Philip Lewis" by Adrian Mourby

******************

The Randolph

Address

Number of rooms / Suites /

Restaurants / Bars

General Manager (2022) Philip Lewis

The Randolph: A Select member of The Most Famous Hotels in the World