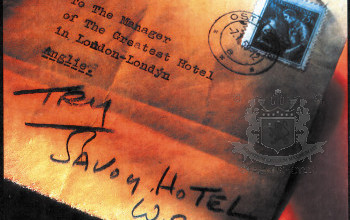

Kitchen Revolt at The Savoy: 16 fiery cooks took their long knives

( words)

On 8 March 1898, The Star (London) wrote: ‘During the last 24-hours The Savoy Hotel has been the scene of disturbances which in a South American Republic would be dignified by the name of revolution. Three managers have been dismissed and 16 fiery French and Swiss cooks (some of them took their long knives and placed themselves in a position of defiance) have been bundled out by the aid of a strong force of Metropolitan police.’ It took an entire day – during which the hotel was guarded by a strong police force – until the situation was under control.

‘A Kitchen Revolt at The Savoy’

What emerged was common knowledge: César Ritz was the first professinal general manager of the Savoy in London. His energies had not been firmly focused on The Savoy at all but rather on his own external business dealings. The long litany of schemes included selling patents for milk sterilisation to the Bernese Alpine Milk Company, promoting the Riviera Hotel in Maidenhead and taking over the hotel Frankfurter Hof.

Ritz became ‘Advisory Expert to the Board’ of the newly founded ‘Egyptian Hotels Limited’ and succeeded in setting up his own syndicate, which was behind the Ritz Hotels in Paris and later London. In 1897, at the age of 47, he agreed to act as Managing director of the Ritz Hotels Development Company for 10 years.

‘So occupied was Ritz with all these things that I should have died of loneliness had it not been for my mother’s presence,’ complained Marie Ritz retrospectively. ‘From all over Europe he was besieged with requests to start hotels and run them if only for a number of months. America offered him fantastic sums to teach inn-keeping de luxe to the New World. Even the famous Herr Adlon was not above asking his advice. Ritz went over the plans for his new hotel in Berlin, made suggestions, and dashed off to Palermo at the appeal of a wealthy Italian speculator who was opening a hotel there.’

The report also disclosed that on many occasions Ritz had solicited backing for schemes from customers and trades people. Subsequently, Ritz was accused of using the hotel to accommodate and entertain friends. Potential partners of their own businesses had been allowed to run up large bills which had never been settled. Presents which had been paid for by the company and had nothing to do with The Savoy’s business had been sent to outside parties with the ‘Manager’s compliments.’ Provisions charged to The Savoy’s account had been delivered to Ritz’s new home in Hampstead. Business was given to firms in which the managers had an interest. All this would have been written off as extravagant manager’s expenses, if business had been doing well. But since Ritz’s attention had been firmly focused on his extracurricular business dealings, he had neglected his managerial duties at The Savoy.

The directors put the matter to Ritz bluntly: ‘When in London you are hardly ever in the hotel except to eat and sleep. You have latterly been simply using The Savoy as a place to live in, a pied-à-terre, an office, from which to carry on your other schemes and as a lever to float a number of other projects in which The Savoy has no interest whatever.’

The investigation also concentrated on maître chef, Auguste Escoffier. He had been left to his own devices without any restraints or controls. As well as a host of his own corporate involvements, he had appointed his own store controller, responsible for checking the weight and quantity of deliveries. As a result, he was able to take commissions and gifts from tradesmen and – it had been discovered – set up his own companies to supply goods to The Savoy at inflated prices without revealing his own involvement.

All this – even with the respectful extra portion of tolerance for the genius of César Ritz – proved to be too much for The Savoy company. Armed with a detailed dossier regarding these malpractices, the directors took action. The note of dismissal delivered to Messrs Ritz, Echenard and Escoffier on 7 March 1898 was uncompromising:

‘By a resolution passed this morning you have been dismissed from the service of the Hotel for, among other serious reasons, gross negligence and breaches of duty and mismanagement. I am also directed to request that you will be good enough to leave the Hotel at once.’

How embarrassing for Ritz. Of course the triumvirate did not leave quietly. Writs started to fly, with suits brought for wrongful dismissal and breach of contract. A whispering campaign began, with Ritz and his colleagues painting themselves as the wronged party. Richard D’Oyly Carte, who by now was more or less an invalid and not allowed to walk, elegantly refused to disclose the details of the managerial ‘abuses’, as they brought no credit to the hotel either. This helped an atmosphere of conspiracy to develop. Ritz had friends in high places who were willing to take his side. They included Edward, Prince of Wales, who declared: ‘Where Ritz goes, I go.’

Finally, on 8 March 1898, The Star titled ‘The Savoy Hotel Mystery’. Shares in the company plummeted overnight. Four days later, the dismissed management team announced that they would be bringing action against the company for wrongful dismissal. They all were immediately employed by the Ritz Development Company and did not need to worry about their personal or professional future. The unpleasant matter was not finally laid to rest until two years later. In 1900, with neither side standing to gain from a public court case, the sacked triumvirate dropped their legal action and signed a mea culpa statement.

Ritz’ assistant Echenard and Ritz together repaid £4,173 and Ritz himself had to repay £6,377 to cover the cost of ‘certain wine supplies’. The famous chef Escoffier, consenting to a verdict against him on the counterclaim of The Savoy Hotel, was to repay £8,000. All was settled amicably and the emperor of chefs, notoriously out of pocket, had to refund only £500 to his previous employers.