The Corinthia London — the good old Metropole

( words)

THE CORINTHIA, LONDON

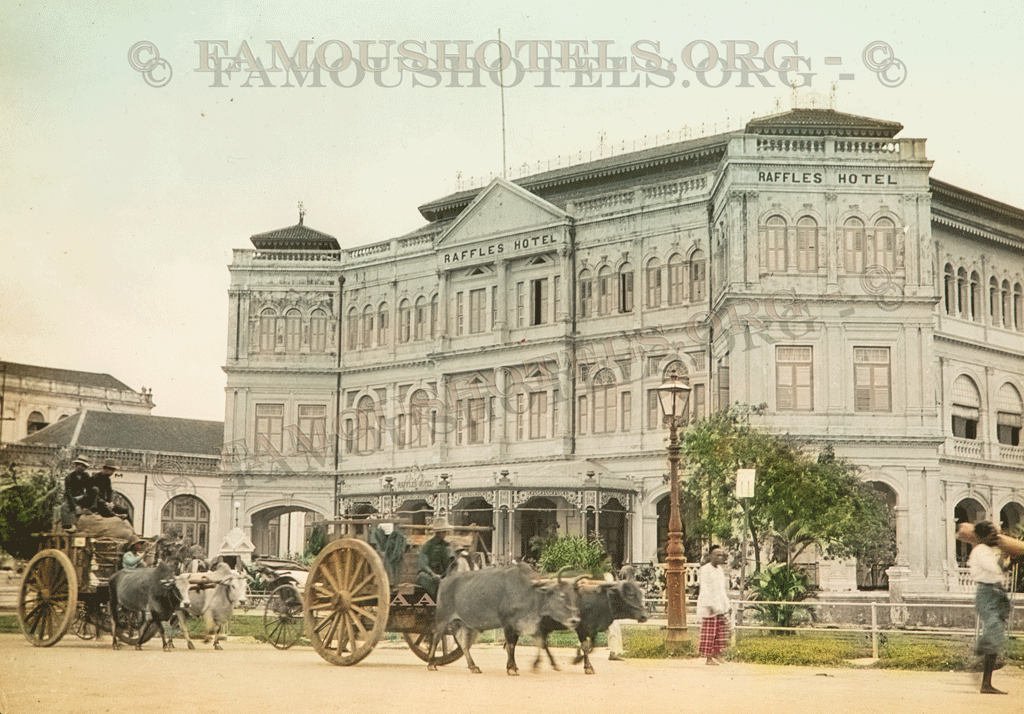

In 2012 a glamorous five-star hotel opened near to London’s Trafalgar Square. However, this was no new hotel. Not at all, just one that had been missing for decades. Unlike many of today's central London hotels, it was not sited in a former bank or newspaper office. The angular building in which the Corinthia, London sits today was actually opened in 1885 as the Metropole Hotel. The builder, Frederick Gordon (1835-1904) of Herefordshire was something of a legend in the world of British hospitality. At the end of the nineteenth century he was referred to as the “Napoleon of the Hotel World”, possibly a soubriquet he had cunningly coined for himself.

London Hotel Metropole 1890

Frederick Gordon had trained originally as a lawyer but in his late thirties, recognising a dire need, he moved into creating elegant restaurants across the British capital, something of an innovation in the wealthy but dreary 1870s. From restaurants it was a short step to building hotels where gentleman diners could also stay overnight. By the 1880s he had become the go-to entrepreneur when a bold new hotel development was required. Gordon was fortunate to be working in London at a time when it was the biggest city in the world, fed with wealth from the biggest empire the world had ever known. Money was no object and Gordon got in early, even before Richard D’Oyly Carte created his world-famous Savoy Hotel in 1889.

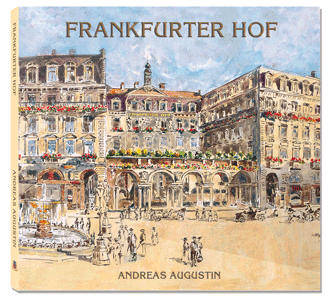

Among Gordon’s many hotels were the Grand Hotel, Trafalgar Square which dominated its next-door neighbour, the Metropole Hotel. He also built and owned the massive seafront Burlington Hotel in the fashionable resort of Eastbourne; the equally massive Brighton Metropole; the Hotel Metropole, Cannes; and the elegant Hotel Metropole, Monte Carlo where he would eventually die in his own suite in 1904.

Spooling back... in 1883 Gordon started work on the Metropole in London. It was one of four towering new hotels commissioned to be built along Northumberland Avenue for the accommodation of the massive influx of affluent international travellers arriving in London daily at nearby Charing Cross Station. Northumberland Avenue had only recently been completed. It was carved out of London’s West End in 1876 following the demolition of the Duke of Northumberland’s old palace close to Charing Cross itself. Local planning restrictions forbade any building to be taller than the width of the road it fronted. As there was an appetite for grand seven-storey hotels in this bustling location, the construction of an unusually wide carriageway was the answer. The Grand occupied a position on Northumberland Avenue very close to Trafalgar Square, which left the Metropole in a smaller, triangular wedge of ground at the less prestigious junction of Northumberland Avenue and Whitehall Place. For this reason, the hotel we know as the Corinthia today resembled New York’s angular Flatiron building on its southern pointed edge.

The Metropole opened in 1885 with an 88-page prospectus extolling the virtues of the hotel’s position on Northumberland Avenue:

In the immediate years following its opening, the Metropole was patronised by the playboy Prince of Wales, Britain’s future Edward VII who kept a box reserved for him in its ballroom. It also acted as the gathering point for competitors in the first London to Brighton Race in 1896, a vintage car event later commemorated in the 1953 Ealing comedy Genevieve.

In the run-up to World War I, because of its proximity to Downing Street and British government offices in Whitehall, the Metropole hotel was requisitioned to provide accommodation for government staff, together with the other three major hotels in Northumberland Avenue. The night before the British Expeditionary Force embarked for France on the outbreak of war in August 1914, its two Commanders-in-Chief, Field Marshals John French and Douglas Haig, both stayed at the Metropole.

In the run-up to World War I, because of its proximity to Downing Street and British government offices in Whitehall, the Metropole hotel was requisitioned to provide accommodation for government staff, together with the other three major hotels in Northumberland Avenue. The night before the British Expeditionary Force embarked for France on the outbreak of war in August 1914, its two Commanders-in-Chief, Field Marshals John French and Douglas Haig, both stayed at the Metropole.

Four traumatic years later, the Metropole reopened with its "Midnight Follies" quickly becoming a well-known cabaret fixture in London during the Roaring 1920s. Bert Firman, aged only 16 became the youngest bandleader in the world at the Metropole.

In 1936, according to hotel records* the Metropole was sold to the British government, this time to house the Air Ministry. From here much of the crucial Battle of Britain was commanded in 1940. The Metropole was also home to other military departments. Bedroom 424 became the home for the recently-created MI9 department and its sub-division the Special Operations Executive. Here much of Operation Overlord (D-Day) was planned.

Right up until 1992 the Metropole housed the bulk of the Defence Intelligence Staff. When the James Bond comic strip was drawn in the Daily Express newspaper, from 1958 to 1983, the artist Yaroslavl Horak used the distinct triangular facade of the Metropole to depict MI6’s headquarters.

In 2007 the Metropole Building and the adjoining complex known as 10 Whitehall Place were acquired for £130 million by a Maltese, Libyan and Dubai consortium. By September 2008 the City of Westminster council had approved development of the two buildings as a hotel and residential complex.

This distinctive triangular building reopened in 2012 as a hotel to be managed by the Maltese Corinthia Group with 10 Whitehall Place sold on as 12 perfectly-located residences. In November of the same year the hotel’s ballroom was the apt venue for the official announcement of the new James Bond movie Skyfall.

Today the Corinthia is probably more glamorous than it has ever been. Its three-year refurbishment clearly cost a small fortune. There are now 263 bedrooms including 51 suites and seven penthouses and a four-storey spa. The Jacobean Library is now Kerridge’s Bar & Grill, named after its host, the Michelin-starred English chef Tom Kerridge. The Restaurant des Ambassadeurs today is known as the Northall Restaurant and is at the apex of that triangular footprint. The restaurant's name is a portmanteau coinage of Northumberland Avenue and Whitehall.

Having recently stayed at The Corinthia, London I have experienced its superb levels of hospitality, service and cuisine. Here in Britain we have a tendency to think that “things ain’t what they used to be”. I suspect, however, that at the Corinthia things are better than they ever were.

Photographs: Kate Tadman-Mourby