Raffles Singapore — A Literary Journey

( words)

For 3 years I lived at Raffles in Singapore. First I occupied Suite 114 on the ground floor of the Palm Court. Followed by Room 336. Finally, for over two years, Suite 254.

By Andreas Augustin

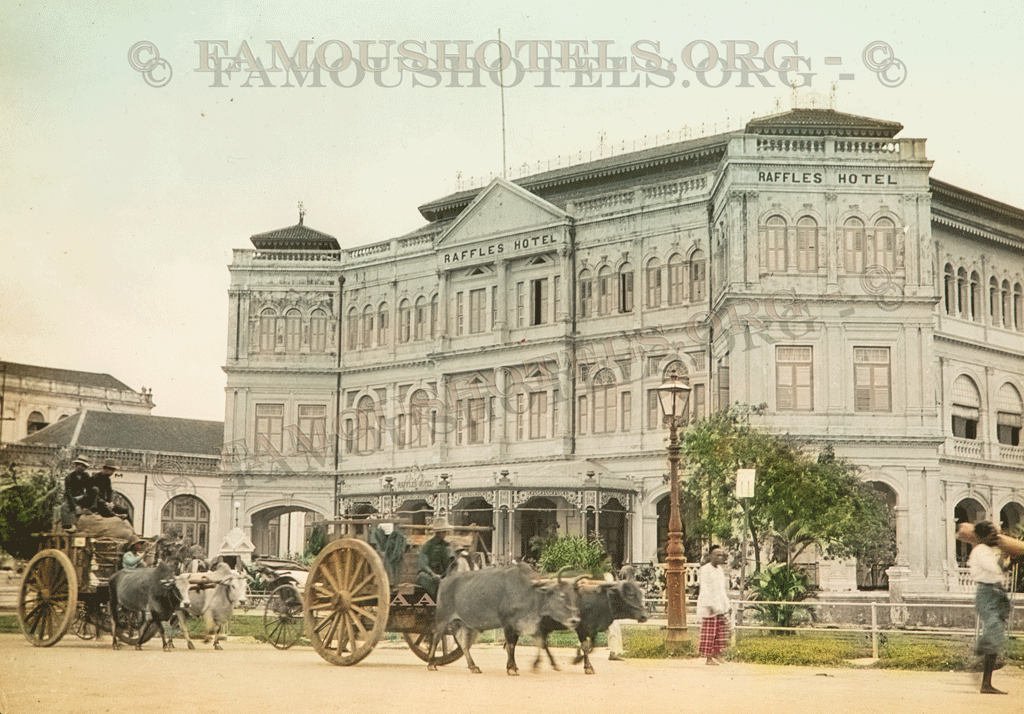

In 1986, Raffles Hotel in Singapore was one of the most famous hotels in the world. It had an incredible atmosphere, 'colonial style', an 'Elizabethan' Grill, named after the Queen of England. They served a splendid 'local' Dover Sole, prawns were caught fresh from a tank in front of the restaurant and head waiters were wearing tuxedos. The maitre d'hôtel, Eric, a white dinner jacket..

In the romantic Palmcourt travellers were sipping Singapore Slings by the gallon. On good days the hotel sold 2,000 cocktails. Tourists were holding on to their straws — in fact to the remains of a colonial past, idealized in fading memories.

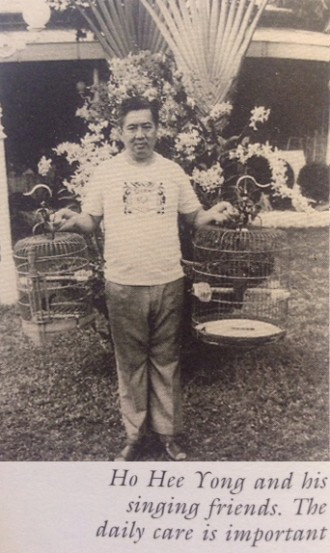

The yard was filled with cages of singing birds, in the possession of a certain Mr. Ho, a chef. He had been given the choice 'the birds or me'. Otherwise his wife would have left him. So he brought them to the hotel, and the smart manager, Italian Roberto Pregarz, declared them a tourist atraction. Mr Ho always mixed a spcial cooking oil for me, with lots of chilly. It was terribly hot.

The yard was filled with cages of singing birds, in the possession of a certain Mr. Ho, a chef. He had been given the choice 'the birds or me'. Otherwise his wife would have left him. So he brought them to the hotel, and the smart manager, Italian Roberto Pregarz, declared them a tourist atraction. Mr Ho always mixed a spcial cooking oil for me, with lots of chilly. It was terribly hot.

There were 124 guestrooms. At the ballroom Raffles was the only Singaporean hotel to offer live music and dancing three times a week. The ballroom stretched out into the street, where the hotel's main entrance and driveway is today. It had been installed there in 1911. Singaporean couples elegantly sailed over the oiled teakwood floor to the sounds of Frisco Soliano and his band. Rumba, Samba, Tango and the occasional Waltz. I wonder where they dance today?

Raffles was at that time single-handedly operated by an Italian, Roberto Pregarz. In 1967, his predecessor had handed him the keys with the words: 'Raffles will close in six months.' With an owner unwilling to invest, his only chance of success was based on his own creativity.

In the tradition of the house, he invited journalists and other writers to stay at Raffles. I noticed that he was always taking very well care of travelling journalists, the most cost-effective distributors of information. He also engaged Singapore writer Ilsa Sharp to research the history of the hotel, laying a solid foundation for many books to follow. Raymond Flower (the author of Raffles - The History of Singapore, The History of The Palace in St Moritz and a series of other books) spent a good part of the European winter at the hotel, producing many of his books there. I would later publish his book Mutiara, Penang (with Sjovald Cunyngham-Brown).

Authors like Russell Foreman resided at Raffles, writing his novel 221 Raffles. And – in all modesty – I moved in for three years, writing a few books there, too. Pregarz added legends to the already existing ones. He changed the location and the name of the bar to Long Bar. When he started, the hotel sold about 20 Singapore Sling per day. Over the new bar he put up a sign board 'Where the Singapore Sling originated'. Over 2,000 (yes, two thousand) of that drink would soon be habitually sold per day. A tiger, shot under the hotel's billiard room, became 'a tiger shot under our billiard table.'

At the western entrance, facing Raffles institution (today's Raffles City), Pregarz created the highly profitable Tiger Tavern Bar for drinking visitors who watched the stunningly beautiful tall slim waitresses in terribly tasteless, cheap 'Tiger-Lily' style miniskirt dresses and high heels, serving pint after pint. I was living right above the Tavern and remember a friend who almost fell over the balustrade of my terrace watching one of the girls.

Pregarz introduced Raffles Tiffin Curry luncheons in the Palm Court, which became a sell-out. People queued for Sunday brunch. He decided to celebrate Raffles’ centenary in 1986, one year early (the hotel was in fact inaugurated in December 1887). ‘Business wasn't good and I needed this promotion vehicle one year earlier,’ he later confessed. Suites were named after important visitors, from Somerset Maugham to Charlie Chaplin.

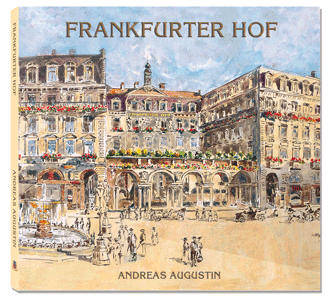

Travelers were asking for souvenirs. Roberto Pregarz opened Raffles Museum. He started putting the name Raffles on T-shirts, mugs, coasters, playing cards, pens, towels and baseball caps. Guest required information about the history of the hotel as well. And they wanted this information in different languages. Hence, in 1986, our first detailed book about the history of a single hotel was published in German: Raffles, Singapore, the first ever book in the series The Most Famous Hotels in the World. Two souvenir shops (one called the Raffles Museum) at the two major entrances of the hotels welcomed around one thousand visitors per day. The books about the hotel sold like hot cakes. Following public demand, we produced a Japanese edition followed by an English version.

Although Raffles - as everybody agreed on - should be saved as a hotel, voices were heard urging for the hotel, this undisputed most famous relic of colonialism, to be replaced by a modern hotel structure. Or, even better, a shopping mall.

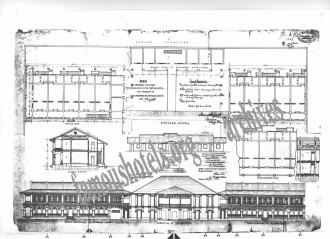

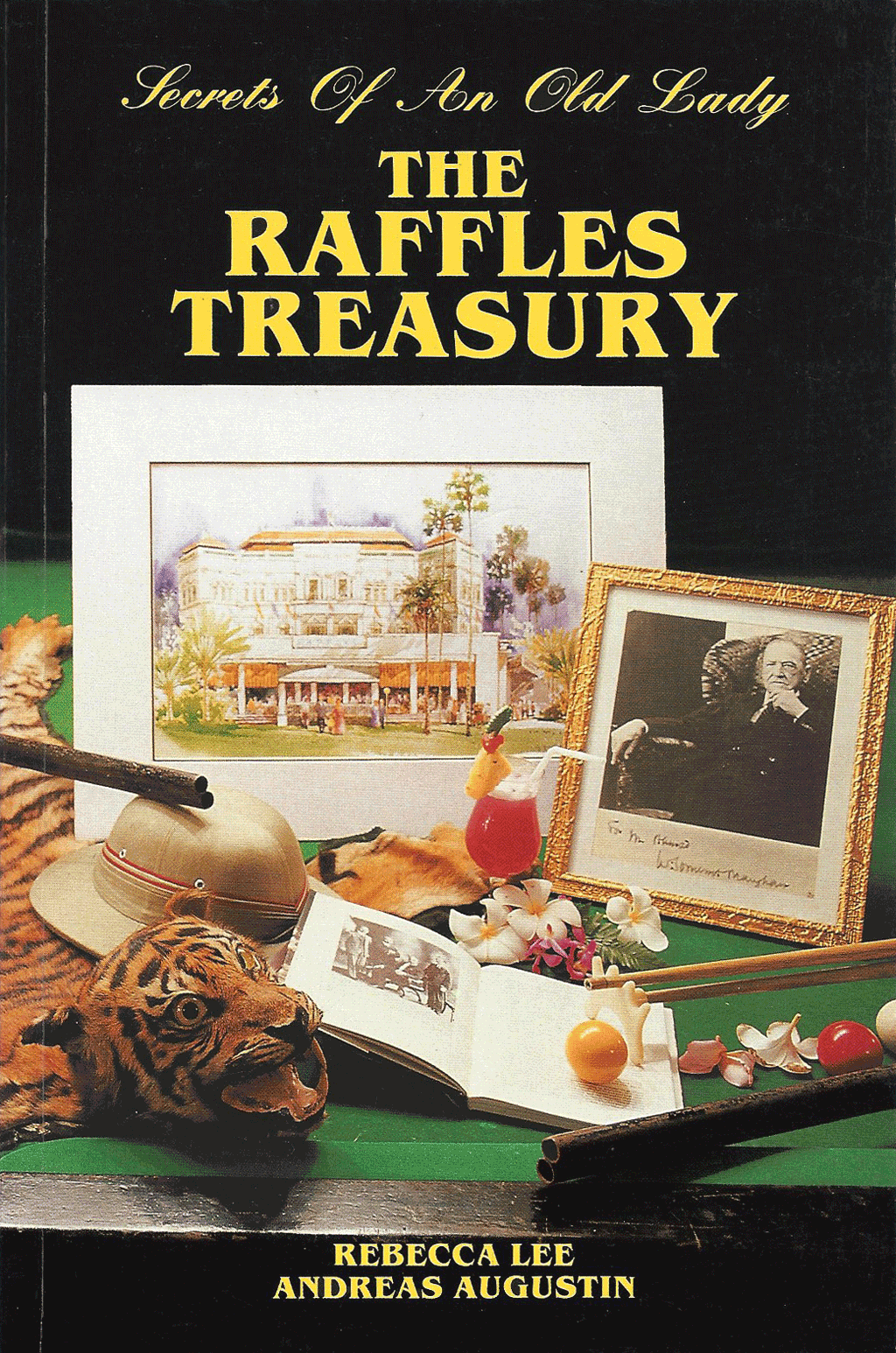

The building had become a patchwork structure of various practical attachments and colonlia heritage: a garage in the back yard, an extra room for the kitchen here, a bay there, a plywood wall in between, and so on. There were no original drawings that would ever enable anybody to restore it to its former grandeur. The plans had been missing for over a century. Not listed as an architectural monument of Singapore, the hotel was basically unprotected. Pregarz used to complain bitterly about the missing original drawings. In 1987, for the real centenary, I decided to produce a smaller volume of my book, a little paperback which every tourist could afford. It would be called The Raffles Treasury, based on all the important questions journalists and travellers used to ask.

During the research for The Raffles Treasury I discovered something strange — a dusty file which looked like it hadn't been touched for decades. With a special permit I entered the secret chamber at the archives in North Bridge Road. There, in a dusty cabinet near the Singapore River, the original drawings of the main building of Raffles Hotel, its Palm Court and the Bras Bassah Road annex had been hiding for almost one hundred years. It had certainly been an adventure finding the plans. But it took a healthy portion of Austrian charm to take them from the lady who protected them.

One of the set of approximately 20 detailed plans of the original bungalow and hotel.

The drawings included the detailed plans of the original bungalow that stood in place of today's hotel, never seen by anyone alive before. Several main sections, roof details, floor plans, porticoes, light installations, the new additions of 1893 (the so called Palm Court Wings), service rooms, stables, cook house, boys quarters and finally all the drawings of the new central block (Raffles as we know it today).

Now these drawings are all part of the famoushotels.org collection. At the time this discovery caused an understandable sensation. It made headlines on the front page of The Straits Times, Singapore's most important newspaper. Ilsa Sharp, the first researcher of the hotel's history, honoured my achievements in this article. Roberto Pregarz almost kissed me and quickly spread the news around the world. Within no time – as it had been promised by politicians for decades – Raffles Hotel became a listed building and was saved from demolition. I'm not sure if all members of the board shared my enthusiasm. That's – in short – how the Italian Roberto Pregarz saved Raffles Hotel.

The Raffles Treasury was launched with a big party. Many wonderful people had helped to compile and write it. Rebecca Lee, a Singaporean student I had the pleasure meeting at Raffles Hotel, helped me writing it. Joan Butler, an other Raffles resident, lent the book an editing hand. Many more friendly spirits helped in prepartation for the book launch, where large copies of the original drawings were displayed on huge boards. I think everybody took more notice of these plans than of my little book. However, from that moment on The Raffles Treasury became the best selling book ever sold in a hotel at the time (picture of the cover of the first edition).

On 15 March 1989, at midnight, Raffles closed for its long overdue renovations.

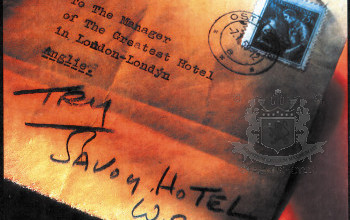

In 1986, on the day of the launch of the first book (28 November), we founded The Most Famous Hotels in the World®, an organisation that would list historical grand hotels around the world. Within no time leading hoteliers like Urs Aeby of The Peninsula in Hong Kong, Gert Prantner of Vier Jahrezeiten Hamburg, Helmut Zunk of Kempinski Berlin (Bristol), Kurt Wachtveitl of The Oriental Bangkok, Michelle Rey of Baur Au Lac Zurich, Richard Kaldor of the Metropole Hanoi, Michael Shepherd of The Savoy London and many others, became keen supporters of our efforts.