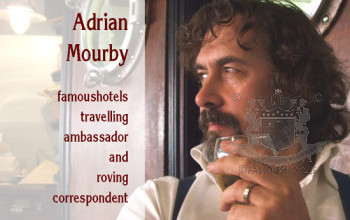

Mourby of Rome

( words)

Adrian Mourby travelled to Rome and landed in history. In search for a decent 'albergo', two books of The Most Famous Hotels library came to aid.

At the time of Italy's Unification in 1870, Rome was already a city of hotels and inns. The best hotels were located between the Porta del Popolo and the Piazza di Spagna (in the ‘Stranger’s Quarter’), bearing foreign names, indeed, like Isole Britannic in the Via Babuino next to the Piazza del Popolo, not far away were the Albergos di Russia, di Londra, di Europa, Brighton, d’Inghilterra, d’America, di Washington and – finally we find an Italian name – the Albergo di Roma.

Two in particular, sited at the base of the Pincian Hill, had distinguished themselves. The Hotel de Russia, situated in a 1818 edifice, built by the great architect and urban designer Giuseppe Valadier, had taken its name from the Russian aristocrats who visited the city and made a temporary home there. It was later renamed 'de Russie'. Meanwhile, in 1845, Prince Marino Torlonia had opened up the old auberge in Via Bocca di Leone where the family used to house guests as a hotel that became much frequented by the English and gained the name Hotel d’Inghiliterra. Both hotels were under the management of Swiss hotelier Francesco Nistelweck (the future son in law of the hotel family Wirth of 'Hassler' fame) and attracted the steady stream of cultural and religious piligrims visiting Rome.

In 1889, Herr Nistelweck achieved his ambition of converting three-storey house near the top of the Pincian Hill into a hotel with views across the city. He called it Hotel Eden and it still stands there today, much enlarged as part of the Dorchester Collection. But Antonio Starabba, Marquess of Rudinì and Italian prime minister, felt a truly modern hotel of the kind to be found in London and Paris was still needed in Rome.

According local legend it was at a reception given by Cesar Ritz at the Savoy in London in 1891 that the Marquis sounded out the great hotelier and his chef Auguste Escoffier about bringing something on a similar scale to Rome. Ritz was managing the Savoy for Richard D’Oyly Carte at the time and campaigning with his aristocratic supporters to open hotel restaurants on Sundays. He was just the visionary Rome needed. So he persuaded D'Oyly Carte, the chairman of the Savoy Hotel, to venture into the Roman enterprise. Carte agreed and invested heavily. For a brief moment in time the Savoy company was an international hotel chain, with hotels in London and – in Rome.

It was decided that the new hotel would be situated on a road leading up the Pincian Hill out of Rome (now Via Vittorio Emanuele Orlando) where the baths of Diocletian had once stood. This site was a mere five-minute carriage ride from Rome’s new Termini station which had begun operating in 1870.

Named Grand Hotel Rome at its opening in 1894, the hotel occupied a third of a new city block. It was designed by Cavaliere Giulio Podesti (1857-1909) and was bigger than many of the Renaissance palaces below in the old city. Podesti filled it with art and antiques and provided a grand stuccoed staircase, an electric lift (still operating today), and Murano chandeliers. There was a panelled billiard room with separate tables “for French, English and Italian players” and a ballroom that brought Belle Époque glamour to Rome.

Moreover hotel history was made in Rome with an advertisement in the national papers saying that Mr Escoffier’s restaurant was accessible “even without residing in the hotel.”

Visiting the Grand today is like stepping straight back into that era. The hotel has spacious, broad public areas and low lighting that would make it a perfect movie set if it were not so busy.

The main foyer is lit from a glassed light-well above and around it are lozenges commemorating four great travellers who must have seemed important in the 1890s.

I counted three faces I recognised J W Goethe (1749 – 1832) Mme de Stael (1766–1817) and Nathaniel Hawthorne (1804-1864). The fourth profile was of “E Hamilton” and the hotel believes this is to be Emma, Lady Hamilton (1765-1815). All four were travellers known for their visits to Italy. Goethe helped further popularise the Grand Tour with accounts of his journey, 1786-1788 and was a particular champion of Naples.

"Naples is a paradise," he wrote. "Everyone lives in a state of intoxicated self-forgetfulness, myself included. I seem to be a completely different person whom I hardly recognise. Yesterday I thought to myself: Either you were mad before, or you are mad now."

Mme de Staal was a French woman of letters who travelled to Italy after the fall of Napoleon for the sake of her husband’s health. As for Nathaniel Hawthorne, he was a writer and diplomat appointed United States consul to Liverpool in 1853, a role described at the time as "second in dignity to the Embassy in London". But when President Pierce left office in 1857, the Hawthorne family, rather than go home, embarked on a tour of France and Italy. Hawthorne, like Goethe and Madame de Stael, wrote about his Italian travels but his most noticeable achievement during his time in Italy was to grow the bushy moustache for which he subsequently became famous.

Emma Hamilton however owed her fame not to literature but to her work as an artist’s model, to her longstanding affair with Admiral Lord Nelson and to her friendship with Queen of Naples. In fact it was at her urging that Nelson aided Queen Caroline in turning Naples into a de facto police state and invading Rome in 1799.

Heroes of the past are always a curious bunch. If you look at the musical pantheon on the exterior of the Opera Garnier in Paris you’ll see a lot of nineteenth-century greats no-one recognised today. But there is no question of the Grand bringing history up to date with some more representative portraits. The Grand Hotel IS history.

After a very short time, Ritz was dismissed and the Roman escapade of The Savoy company had come to an end. Today the Grand is known as the St Regis Rome. Its 200 bedrooms have come down to 138, with 23 suites, following the inevitable expansion of room size in the twentieth century, but with its combination of Empire, Regency and Louis XV styles, it remains a wonderful connection to the nineteenth century Rome.

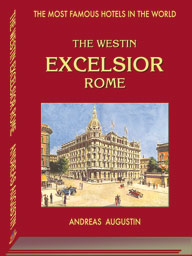

On 17 January 1906 the civic authorities, including the Prime Minister, the Mayor, Commendatore Cruciani Alibrandi and all the city council and the press were invited to a formal dinner to inaugurate Rome’s majestic new hotel, the Excelsior, located in the Ludovisi area, on the corner of Via Veneto and Via Boncompagni, opposite Queen Margherita’s palace. 160 colourful pages of history of the Excelsior in Via Veneto – a story of life on the fast lane.

(From 'Westin Excelsior Rome', by Andreas Augustin and Thomas Cane)

Further up Via Vittorio Emanuele Orlando, a mere eight-minute walk past the US Embassy, stands the hotel that began the next revolution in Roman hoteliery. Dubbed “the most Parisian in Rome” when it opened in 1906, the Hotel Excelsior stands on what is now called Via Vittorio Veneto (after the famous battle of 1918).

An equally impressive and even bigger building, The Excelsior has more architectural flourishes than the St Regis. A great Jugenstil cupola dominates your approach to the hotel and over its triple-arched entrance are carvings of African, Asian, European and American caryatids that are almost caricature. Inside however is all glass and gold with lots of light from large windows. The building was designed by two Italian architects Emil Vogt (1863 – 1936) and Otto Mariani (1863-1944) and constructed for Baron Alphons von Pfyffer of Switzerland who sold it in 1920 to the Compagnia Italiana Grandi Alberghi.

In 2000 a two-storey apartment was built inside that cupola which is now known as "Villa la Cupola" and is one of the most expensive hotel suites in the world. With several terraces, seven bedrooms, a dining room, a private cinema and gym, the Villa is truly opulent -- as befits the lifestyles of some of those who have stayed at the Excelsior.

If the St Regis is history then the Excelsior is the movies. In 1957 the hotel hosted the cast and crew of Ben-Hur and in 1960 the exterior of the Excelsior featured in La Dolce Vita with actor Lex Barker slapping Anita Ekberg across the face at the entrance (after her famous dip in the Trevi Fountain) and then turning to punch the odious Marcello Mastroianni who collapses - to general satisfaction - against the front of the hotel.

In 1962 the hotel also featured in the Kirk Douglas film Two Weeks in Another Town in which a washed-up actor (Douglas) takes an assignment in Rome in the hope of professional redemption. The Excelsior also featured in the 1983 Robert Mitchum WWII miniseries The Winds of War (1983), a very accurate piece of location-casting. After the fall of Rome in 1944 the hotel was occupied by American General Mark Clark who had long made it is ambition to be the first allied general into the Italian capital.

In 1998 the Excelsior was sold to Starwood Hotels who renamed it The Westin Excelsior, Rome. Despite the increase of room sizes, the hotel still boasts 316 bedrooms and 35 suites. It is currently celebrating 110 years in the hospitality industry and the hotel restaurant, Doney is serving a menu based on dishes from the original 1906 gala dinner that opened Rome’s newest hotel.

For the next big development in Roman hotels you have to go out beyond the Vatican to Monte Mario and the splendid Rome Cavalieri, a "Hollywood on the Tiber" resort hotel inaugurated in 1963 by Conrad N Hilton himself.

But that's another story...