From Transit Stop to Destination

( words)

By Adrian Mourby

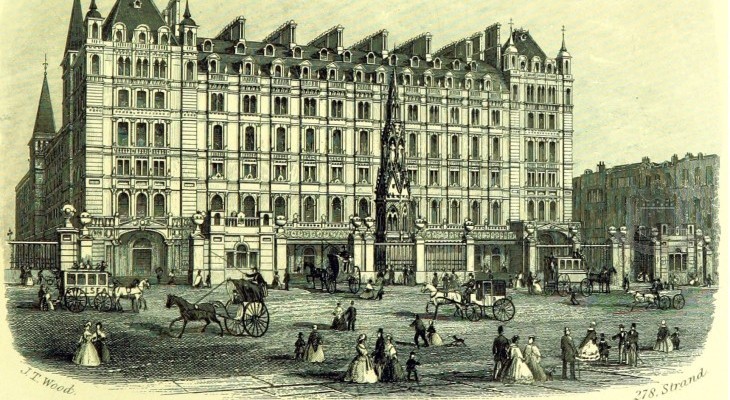

Charing Cross is one of several Victorian railway terminus hotels built in London in the 19th century. Opened in 1865 above its station, it served as the grand arrival point for Calais–Dover boat passengers — travellers from the Continent, then the most important of all. In that age of glamorous rail travel, the most expensive rooms overlooked the railway platforms, while the prestigious Strand view was of lesser value.

Charing Cross is one of several Victorian railway terminus hotels built in London in the 19th century. Opened in 1865 above its station, it served as the grand arrival point for Calais–Dover boat passengers — travellers from the Continent, then the most important of all. In that age of glamorous rail travel, the most expensive rooms overlooked the railway platforms, while the prestigious Strand view was of lesser value.

In the 1980s, the station was redeveloped and the air space above the platforms used for new office accommodation. Designed by Terry Farrell, Embankment Place rests on a concrete raft put in place of the 1906 roof.

Today, the Clermont Charing Cross pairs its Victorian railway‑age grandeur with the futuristic, spaceship‑like station that now spans the Thames, and a prime location in the heart of London.

The Clermont Charing Cross is one of several Victorian railway terminus hotels built in London in the 19th century. By 1850 the British capital was already the largest city the world had ever known, forging railway links with the rest of the country. Instead of a single central station, London built a ring of them: Euston to the north, Liverpool Street to the east, Paddington to the west, and Charing Cross to the south, connecting all the way to Dover.

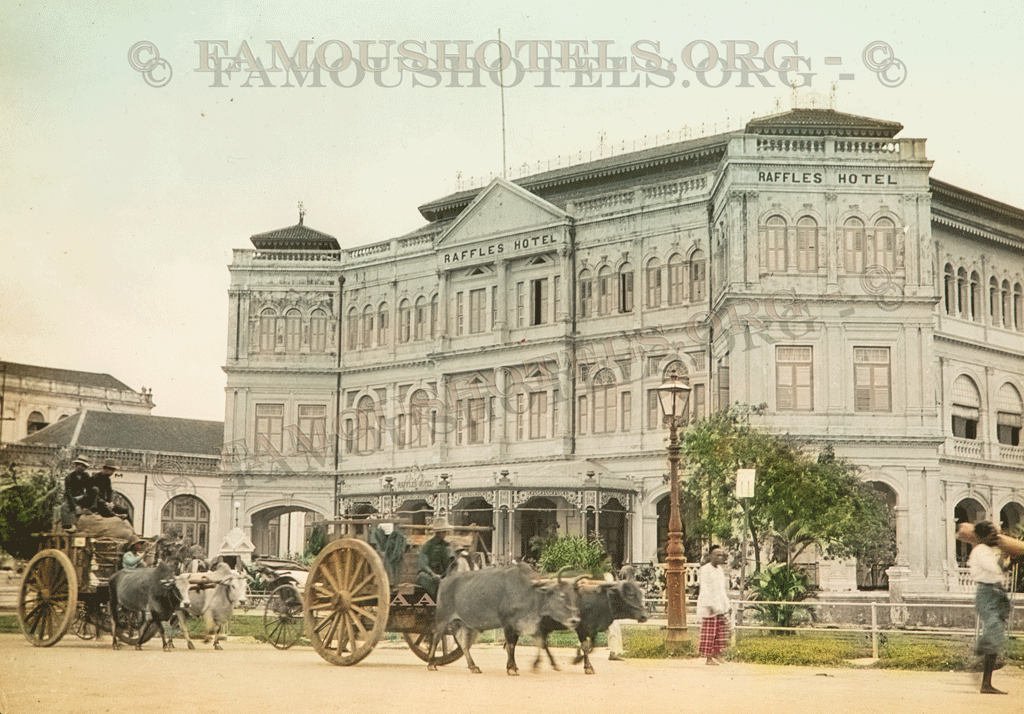

Each station had its palatial hotel. At Paddington, the Great Western Royal Hotel was the brainchild of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, conceived as the start of a GWR journey all the way to New York. St Pancras was arguably the most beautiful — a veritable cathedral of a hotel designed by the Gothic Revival master George Gilbert Scott. Yet the Charing Cross Hotel was premier. Built above Charing Cross Station, it served the boat train from Calais, receiving European visitors for their first night in England. Interesting to Note: Around 1900, some 100 of the largest hotels in the United Kingdom were run directly by the railway companies themselves. By parliamentary act, they were granted permission both to build and to operate these hotels — a recognition that such ventures were in the public interest. The arrangement greatly boosted travel and the profitability of the British railways. The Midland Railway, for example, estimated that without its grand Manchester hotel, some 40,000 travellers in 1904 would not have stayed overnight in the city at all. The Midland Hotel in Manchester was then one of the largest and most prestigious hotels in England, employing 400 staff, serving 1,000 meals a day, and in its celebrated German restaurant selling some 80,000 portions of German specialities and half a million glasses of German beer annually

Each station had its palatial hotel. At Paddington, the Great Western Royal Hotel was the brainchild of Isambard Kingdom Brunel, conceived as the start of a GWR journey all the way to New York. St Pancras was arguably the most beautiful — a veritable cathedral of a hotel designed by the Gothic Revival master George Gilbert Scott. Yet the Charing Cross Hotel was premier. Built above Charing Cross Station, it served the boat train from Calais, receiving European visitors for their first night in England. Interesting to Note: Around 1900, some 100 of the largest hotels in the United Kingdom were run directly by the railway companies themselves. By parliamentary act, they were granted permission both to build and to operate these hotels — a recognition that such ventures were in the public interest. The arrangement greatly boosted travel and the profitability of the British railways. The Midland Railway, for example, estimated that without its grand Manchester hotel, some 40,000 travellers in 1904 would not have stayed overnight in the city at all. The Midland Hotel in Manchester was then one of the largest and most prestigious hotels in England, employing 400 staff, serving 1,000 meals a day, and in its celebrated German restaurant selling some 80,000 portions of German specialities and half a million glasses of German beer annually

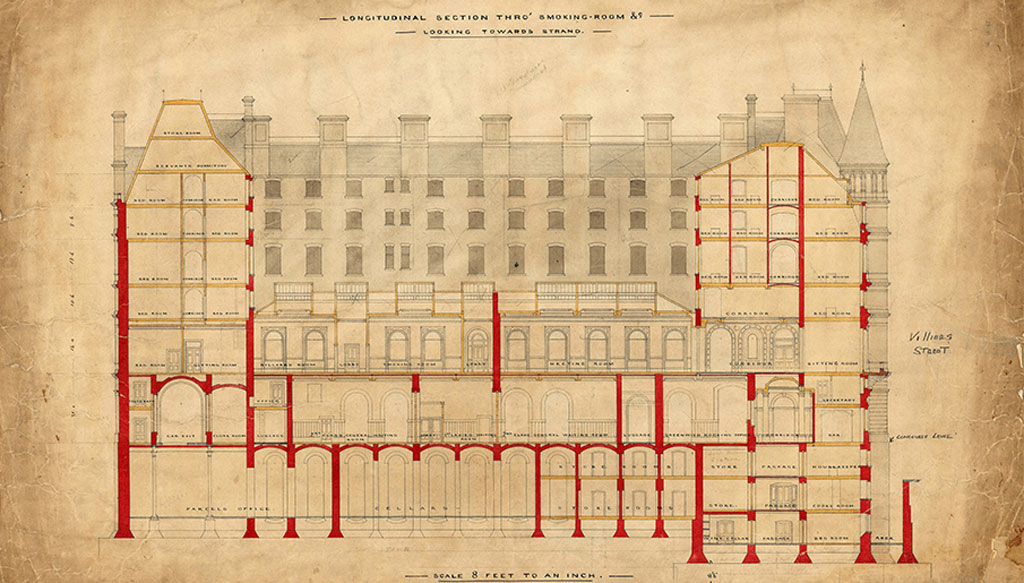

Back to London: soon other hotels clustered nearby — The Strand, The Grand, the Metropole (now the Corinthia) — but the Charing Cross Railway Hotel came first. It was designed by Edward Middleton Barry RA, son of Sir Charles Barry, who shaped Victorian Britain with works including Trafalgar Square, the rebuilt Palace of Westminster, and many country houses. Sir Charles favoured a florid yet neoclassical style. His third son Edward was more versatile, designing both the station and the hotel. The blunt yellow-brick façade was relieved by two extravagant first‑floor conservatories overhanging the east and west entrances, and the roofline was crowned by two mansard turrets — later lost to the Luftwaffe in 1941.

The hotel was built in 1863–64 by Charles and Thomas Lucas, also engaged on the Langham Hotel near Regent’s Park, and later the Albert Hall. The Charing Cross opened on 15 May 1865 with its station. Passengers walked beneath the hotel to reach their trains. It had 250 bedrooms over seven floors. While the front faced the Strand, the priciest rooms overlooked the platforms — train travel then was a mark of glamour.

After the war, the top two floors were rebuilt in 1953 to designs by F.J. Wills & Son. The new roofline was more functional, with a hint of Art Deco squareness, yet it suited the building better than the old mansards. One repair was never made: debris from the wartime blast dented the elegant handrail of the grand staircase leading from bustling ground‑floor London to the piano nobile. The dent remains, polished to a gleam.

The hotel is home to a covered footbridge, built in 1878, that connects the original building on the western side with the newer addition to the east, and stretches over Villiers Street between Embankment and Strand. In addition, a small museum showcasing the history of the hotel can be enjoyed as part of the hotel stay.

On the first floor are a bar, the dining and breakfast room, and the two conservatories, now used for events. Breakfast here offers fine views of the Charing Cross monument. Traditionally this was the point from which all distances from London were measured. The original 13th‑century cross marked the bend in the Thames — from the Old English ċierring — with Westminster upstream and the City downstream. Destroyed under Cromwell’s Commonwealth, it was rebuilt after the Restoration of Charles II, now standing some 200 metres east of Trafalgar Square.

Originally built to house continental train travellers, the modern‑day Clermont Charing Cross has taken on a new role since its 2022 reopening and rebranding. It is a short walk to Trafalgar Square, the Houses of Parliament, and the West End theatres, and close to the National Gallery, National Portrait Gallery, and Royal Academy, as well as Leicester Square, home to UK film premieres.

Built for one purpose, the Clermont Charing Cross now thrives with another.

Built for one purpose, the Clermont Charing Cross now thrives with another.

FAMOUSHOTELS HISTORY CHECK

The Clermont Charing Cross – History Presentation Review

Positives

-

History is clearly linked to the railway age and Victorian heritage. A small museum showcasing the history of the hotel can be enjoyed as part of the hotel stay.

-

Architectural highlights — Edward Middleton Barry’s design, the grand staircase, and ballroom — are mentioned.

-

Notable guests, including Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, add depth and prestige.

-

Anniversary celebrations and external press coverage reinforce its heritage value.

Negatives

-

No dedicated History page or visible history button in the main navigation — content is buried under blog or “About”.

-

No structured timeline of key events such as opening dates, expansions, or wartime repairs.

-

Lacks the fully branded heritage narrative expected at a Famous Hotels level.

-

Missed opportunity to feature archival photography and richer guest stories in the public presentation.

Archival material: Custard Communications, The Network Rail archive (The Network Rail archive is the custodian of a vast collection of historic documents and plans relating to today’s railway infrastructure)