César Ritz’s Waterloo (1)

( words)

Part 1 by Andreas Augustin

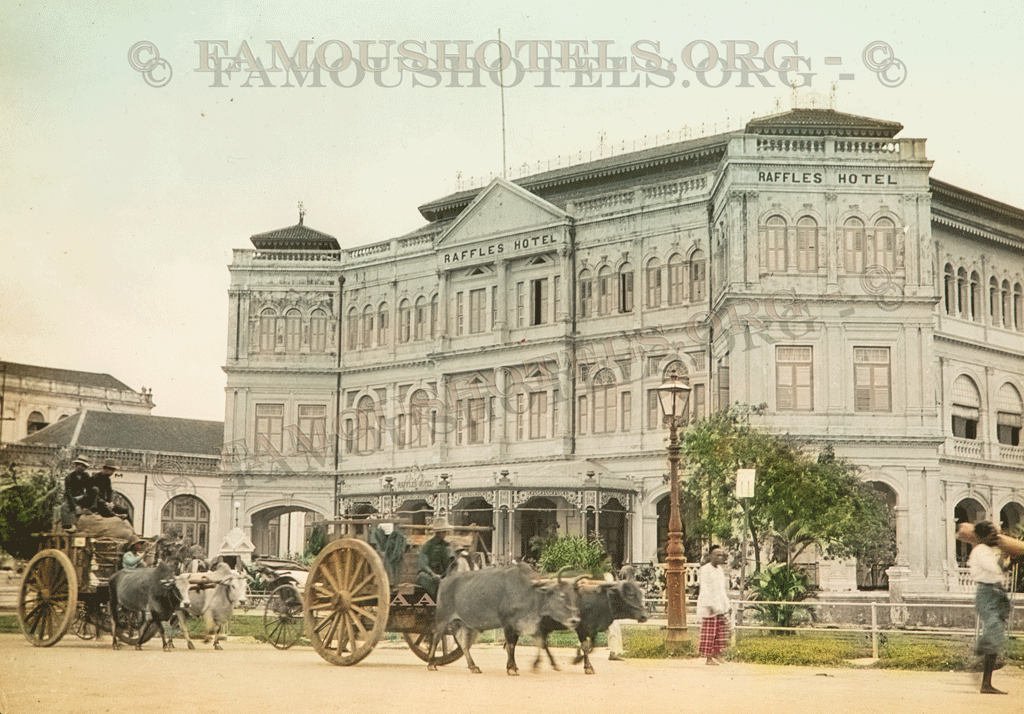

We find ourselves in the heart of London's theatre district, on the Strand. We are deeply immersed in the history of the most famous hotel of London's Westend The Savoy. We imagine the clatter of horse-drawn carriages, encounter famous figures such as the Prince of Wales, Oscar Wilde, Nelly Melba, Auguste Escoffier, the composer Arthur Sullivan, Enrico Caruso, ... OK, I shall cease; this list could continue indefinitely. And then, of course, there was one more: César Ritz.

London, The Savoy

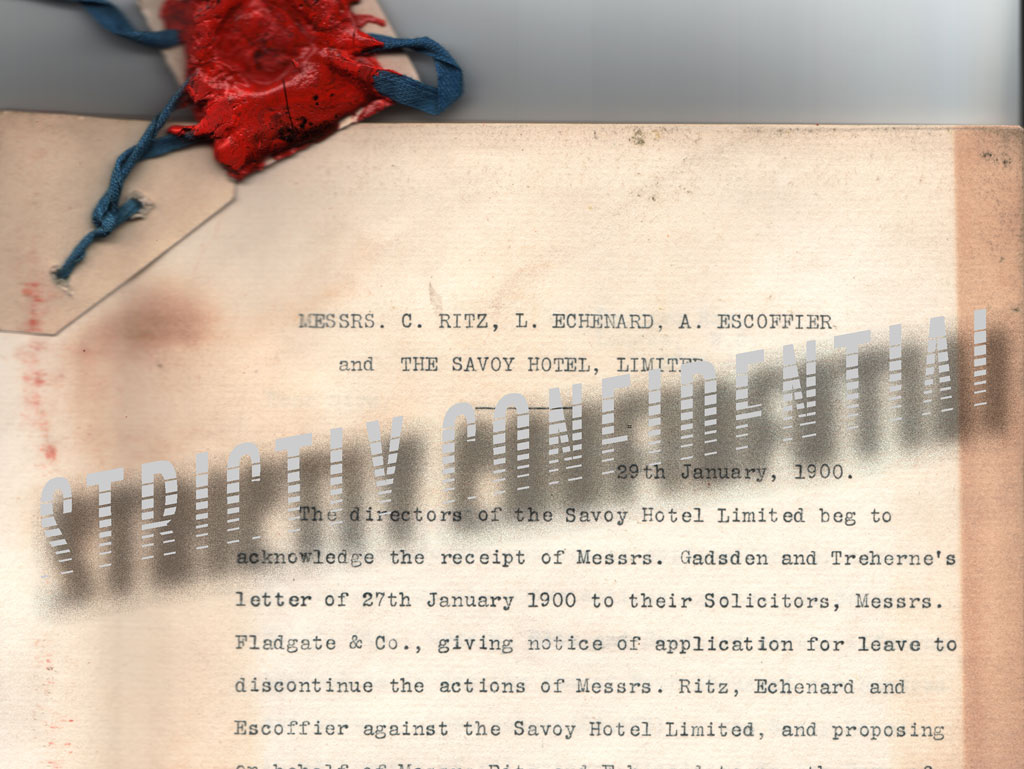

Every night at midnight, the late shift in the kitchen had a set task: to prepare Bircher muesli. I sat on a stool in the kitchen, consuming a steak sandwich. It had become late once more. The kitchen (under Anton Edelmann) was situated a level above the Savoy's entrance from the Thames, and a floor below the driveway from the Strand. My late visits were anticipated. After all, I was on the same floor, next door in the archives. Yet today, my appetite had waned. I was simply too exhilarated. Could what I had just discovered in the archives truly be real? It was an incredible tale. A splendid story. A real sensation.

From the beginning.

Susan Scott, the Savoy Hotel archivist in London in the year 2000, oversaw a cluttered storeroom masquerading as an archive. When General Manager Michael Shepherd informed her that I would have unrestricted access to this "archive," she swallowed hard.

"Unrestricted?" she inquired. "For how long?"

"As long as it takes," said Shepherd.

Then, my London colleague Andrew Williamson and I delved into mountains of files. A room, approximately five by five metres, and four metres high, plastered with metal shelving units. These, in turn, packed with boxes and folders. Some labelled, some a complete surprise. We commenced our work. Every hour, we needed to step outside for fresh air and to wash our hands.

It rapidly became clear to us that the archive extended back to before the hotel's opening. Around 1884. Those were the days of theatre impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte, who had envisioned The Savoy Hotel beside his Savoy Theatre as a modern and luxurious retreat. Returning from one of his numerous American tours, he was convinced by the "Grand Hotel" project. You could read all these details in our book, where over 220 pages, we provide an intimate insight into the creation and life of this fantastic establishment. However, what fell into our hands that day exceeded our wildest imagination. In a notably well-sealed box, the hotel by the Thames concealed a dark secret.

And now from the very beginning: It was an undeniable fact that Richard D’Oyly Carte had established a sensational establishment with the Savoy. However, he was a theatre impresario. His speciality was filling theatres, not hotel beds and restaurants. The Savoy had plenty of both. The River Terrace offered over 100 seats that needed filling. The Savoy Grill, the conservatory, all were F&B outlets with a total of 500 seats. At that time, there was no High Tea in the lobby.

The hotel – designed entirely after an American model, was considered collapse- and fire-proof. For the first time, a hotel was built entirely with a steel structure. Its own power plant generated electricity, a deep well far below the Thames' groundwater supplied the hotel with fresh water, which bubbled up in a courtyard fountain and was heated into all baths. "Do you intend to accommodate amphibians?" a civil engineer asked when he noticed in 1884 that every room had a bath and every bath a bathtub. The Victoria Hotel, also opened around 1889, had four bathrooms for 500 guests.

The opening was sensational. All of London rolled through the narrow entrance into the new hotel's courtyard (today, this courtyard is covered and glazed over as the Thames Foyer). The excitement was immense. Yet D’Oyly Carte, as a man of the theatre, was all too aware of the danger of the nine-day wonder. For nine days, curiosity reigns, and people storm the new and unknown to explore, sniff around, love, or ... reject it. A hotel, however, was not a theatre play for a season. It had to be engaging throughout the year. It had to offer something on its stage that was nowhere else to be found. Otherwise, after the illusion of a gifted premiere came the reality of a half-empty establishment.

A little bird of noble bearing whispered to D’Oyly Carte that at the Hotel National in Lucerne, Switzerland, a certain César Ritz was working as the director. It is now pertinent to note – and I quote from the memoirs of a contemporary of Ritz who had observed him at the Grand Hotel National – "Were Mr. César Ritz not to introduce himself expressly as the manager of this splendid establishment, one might mistake this refined and distinguished figure for one of the most noble and illustrious aristocratic guests of his hotel. Mr. César Ritz gives the impression of a gentleman from head to toe — embodying the finest social graces, fluent in the languages of all cultured nations, making him appear as a native to French, English, Russian, and Italian guests alike. This phoenix of a hotelier casts a truly enchanting impression on everyone within the first few minutes, an impression that makes it quite understandable why the aristocracy almost without exception honors the Grand Hotel National."

With this reputation, Ritz approached D’Oyly Carte. Carte was interested in the Swiss man, around whom half the high nobility of Europe seemed to congregate. Furthermore, he maintained excellent connections with the American financial aristocracy, whom he had supported as a reliable hotelier on the Côte d'Azur, in Baden Baden, and indeed in Lucerne. The Vanderbilts, the Morgans, the Astors – for them, César Ritz was the point of contact. César Ritz, who had been dismissed as a boy from the inn Trois Couronnes in Brig, Switzerland, with the words "Boy, the hospitality industry requires a special talent... and you utterly lack it!", had made it.

Children Christmas at The Savoy

Children Christmas at The Savoy

The diminutive man had developed the ambition to make something of himself. He observed his clientele: the fine tailored suits, the elegant footwear, not merely nailed together but the leather finely crafted with the sole, the original hats made from the finest felt. And the gestures. How the Prince of Wales casually pulled his watch on its golden chain from his waistcoat pocket, when to cut one's cigar, when to offer a light? Europe's grand dandy, a fashion idol of the high nobility and, after all, the future king of England, had caught his attention. He had followed him since the Vienna World's Fair in 1873, then again in Paris. This little waiter was always at hand. Soon it was the other way around, and the Prince of Wales is said to have remarked, "Wherever Ritz goes, I go!"

An essential part of Ritz's success was the culinary element, within which a certain Auguste Escoffier moved as proverbially as a fish in water. The Prince of Wales traveled specially to Monte Carlo to taste the French chef's specialties at the Grand Hotel. For the Poularde Derby, stuffed with rice, truffle, and foie gras, the portly heir to the throne would have trekked on foot. Later, he would serve him frog legs. This earned the French the English nickname "Froggies" and Escoffier a severe rebuke. The Prince of Wales eats everything, but certainly not frogs, he was informed.

Thus, the Ritz ecosystem gradually formed. Ritz and Escoffier were considered a power duo, a complete gastronomic concept. In this environment, a retinue of talented young hoteliers emerged, deployed by Ritz in his various hotels along the Côte d'Azur, in Baden-Baden, in Switzerland. And now, thus, the most modern hotel in London beckoned.

In the resorts of the continent, César Ritz was confined to the summer season. Each summer had to earn the money for the quiet winter months. However, London, as the capital of the British Empire, would offer the flair of a metropolis all year round. Ritz negotiated fiercely with Carte. For his first visit, he charged a proud £350 (difficult to convert, today representing a purchasing power of a hundred thousand pounds). Then he played hard to get. He had to attend to his businesses on the continent. His time was limited. Thus, he suggested installing his employee Louis Echenard as the director at the Savoy. A £500 annual salary would be a fitting remuneration. Initially, he concealed that Echenard was his head waiter.

Yet, Carte wanted Ritz personally. "I offer you £1,000 per year."

Ritz considered it. From this Savoy in London, he could probably make the best hotel in the world. It lay there by the Thames like a gleaming new Atlantic liner, just without a captain. The offer was incredibly generous. On the continent, a quarter of the sum was hardly paid for this position. Bold as he was, he gambled a round further: he demanded, for this sum, not to have to be present in London the whole year, but only six months. Furthermore, he demanded unrestricted freedom of action. For the time of his absence, he had already the right man up his sleeve: Louis Echenard. To lure the Londoners out of their clubs and activate the ladies of society, he played the culinary ace. Auguste Escoffier had to be part of the team. This would mobilize the ladies along with their husbands to go to the restaurants. After the theatre, for example.

Carte swallowed. Yet, he had no choice. He wanted this Swiss hotelier at any cost. He could also sell to the board that Auguste Escoffier would be part of the team. Carte had an infallible instinct for talent. On stage and in life. He hired Ritz, gave him all the freedoms he wanted, and paid what was demanded. Now he had a fantastic frontman and could turn back to his theatrical work. Oscar Wilde's American tour was upcoming. Ritz would deal correctly with his snobbish clientele. "Feel free to throw someone out if they're a nuisance!" he told Ritz on parting. "But, Mister Carte, I certainly won't do that. You must remember, the guest is always right."

Ritz, 39 years old, moved to London. With him, his wife Marie. And Echenard, the finest wine expert on the continent, Escoffier, already over forty, who would refuse to learn English ("Otherwise I'll cook like them!"), his loyal cashier Agostini from Monte Carlo, and gradually a tail of devoted vassals. The Ritz ecosystem spread out. That it would become the greatest morass of English hotel history of the 19th century was not foreseeable at that time. It had been kept secret long enough.

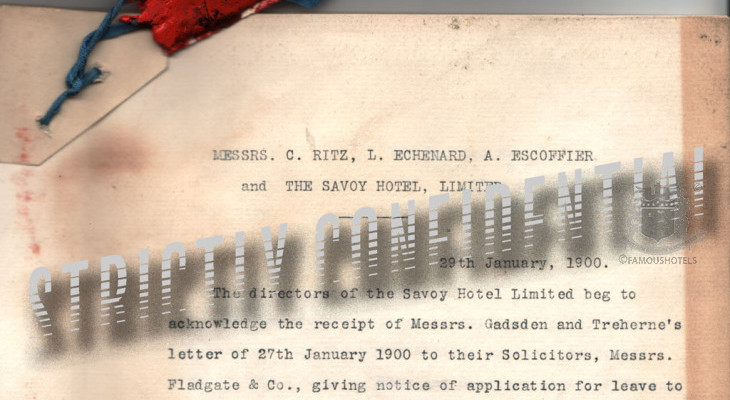

Until that magical night when we opened that one box, on which in faded letters was written: "Strictly confidential."