1932: Flying from Europe to Asia

( words)

The last stop before Bangkok was Rangoon. After flying over dense jungle, the mountains gave way to flat irrigated paddy rice fields and soon Don Muang, Bangkok’s airport, was reached.

The last stop before Bangkok was Rangoon. After flying over dense jungle, the mountains gave way to flat irrigated paddy rice fields and soon Don Muang, Bangkok’s airport, was reached.

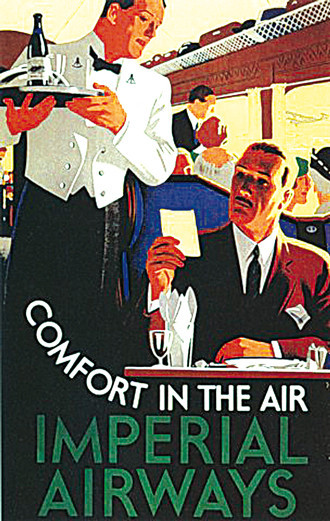

In March 1924 the British formed Imperial Airways (the forerunner of BOAC and British Airways), ringing in the age of passenger air transport. For countries like the Kingdom of Siam, the develpment of air traffic was paramount ending Siam’s relative isolation and enhancing communications with the outside world.

May 1936 saw the arrival on a proving flight of the first four-engined Short C-Class Sunderland, a 24-passenger luxury flying boat, a great step forward from its predecessors. The all-metal, high-wing Sunderlands had been designed for the Empire Air Mail program, for which Alexandria served as a hub. By 1938 the airline was carrying some 2000 tons of mail annually.

The English Short brothers developed flight boats for the Africa and Asia traffic. The flight boats offered every luxury. 16 passengers, all seated at elegantly laid tables facing each other, were served from lavish buffets, gazing through panoramic windows with curtains drawn. Windows could be opened and passengers were strictly advised not to throw anything out.

An advertising campaign by Tom Purvis for Imperial Airways was a huge success. For a long time, even airships were seriously considered for long haul travel. When airship R101 crashed on its flight to India in 1930, this issue was shelved for the time being.

Imperial Airways, by the way, was the first company in the world to hire air hostesses. The fact that all the ladies were trained nurses sheds light on the difficulties expected along the route, doesn’t it? ‘Travel from London to Bangkok in only nine Days!’ the Aerial Transport Co of Siam proudly announced in 1930. ‘America now only fifteen days distant, Japan six days, Hong Kong two days.’ In 1939, the Boeing Stratoliner took this leisure to even dizzier heights, with pressurized cabins and air conditioning and seating for 33 passengers. For the first time, a passenger plane could rise above bad weather.

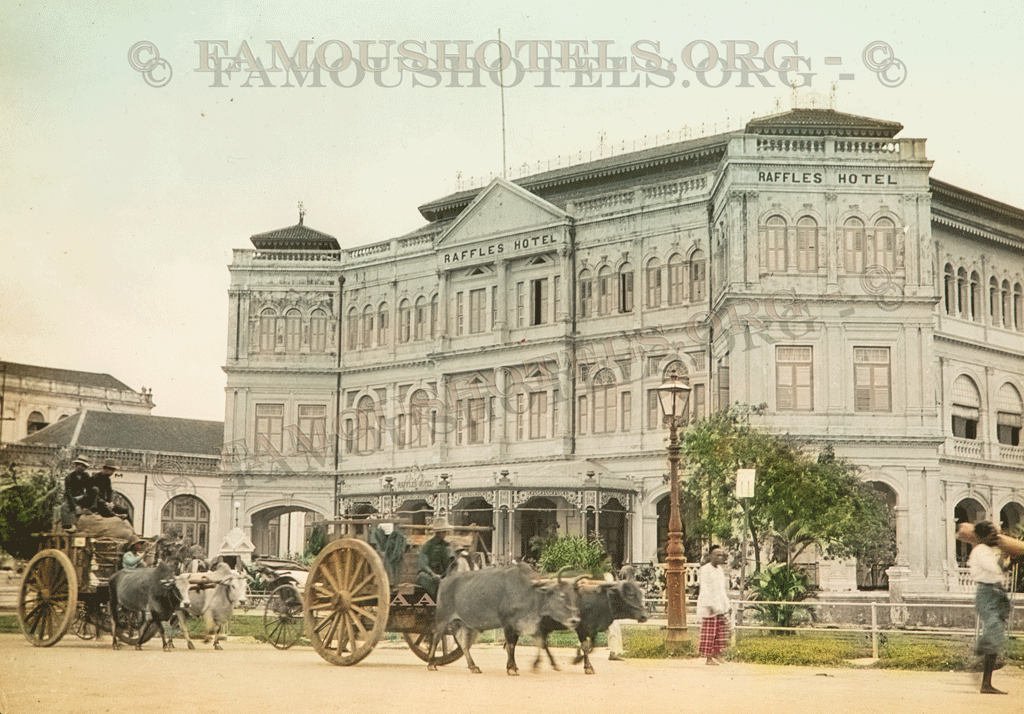

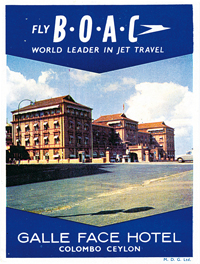

Famous Hotels along the route from Europe to Asia became "Airline hotels", like the Galle Face in Colombo.

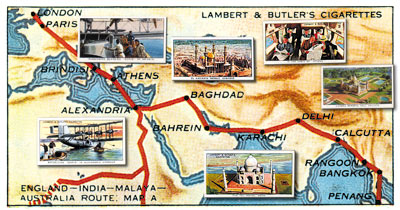

While a steamship on its route from Europe to Indonesia would have never come near Bangkok, the 1932 KLM schedule from Amsterdam to Batavia in a Fokker F-12 or F-18 was very different. The flight path (duration of each flight determined by hours of daylight, sandstorms, monsoons, etc.) were: Amsterdam – Marseille – Rome – Brindisi – Athens – Mersa Matruh – Cairo – Gaza – Baghdad – Bushir – Djask – Karachi – Jodhpur – Allahabad – Calcutta – Akyab – Rangoon – Bangkok – Alor Star – Medan – Palembang – Batavia. En route stopovers at night, in hotels or guesthouses, were part of the schedule and were included in the ticket.

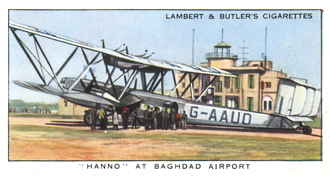

Hanno at Baghdad Airport

Passengers, on the other hand, liked the service and the aircraft. Sir Montagu de P. Webb, who made a number of early air trips between England and India, effused in 1933 about a trip from Karachi, including the Baghdad-Cairo leg aboard the HP42 Hanno : "London in five days—what more could one want!" He described a strong headwind on the leg from Rutbah Wells to Gaza:

But what is this? Our engines are slowing down, and we are descending to earth. Landing so gently as to be almost unnoticeable, our Engineer steps out and runs ahead to show the way to some unknown destination. Taxiing after him, Hanno comes to rest over a small circular iron cover to what is clearly a large receptacle underground. In fact, it is an emergency petrol supply. Our Captain, faced with the possibility of more strong head-winds before reaching Gaza, decides as a precautionary measure to take in more petrol. So we all alight and watch the proceedings.

The last British biplanes operated by Imperial Airways on the Cairo-Baghdad run were both tri-motors: the De Havilland DH66 Hercules, which carried seven passengers at 178 kph (110 mph), and the Armstrong Whitworth Argosy, which carried 20 passengers at 155 kph (96 mph). They were succeeded by the first of the four-engined, all-metal monoplanes: the Armstrong Whitworth Atlanta, whose speed exceeded that of biplanes by only some 25 percent; the De Havilland Albatross, which could reach 340 kph (210 mph) carrying 22 passengers, and the Armstrong Whitworth Ensign, whose capacity was 40 passengers but which cruised at 275 kph (170 mph).